Le persone con GERD più grave possono avere rigurgito di cibo dallo stomaco nell'esofago o nella bocca, in particolare quando le attività aumentano la pressione nell'addome, ad esempio, con tosse e flessione.

Le persone con GERD più grave possono avere rigurgito di cibo dallo stomaco nell'esofago o nella bocca, in particolare quando le attività aumentano la pressione nell'addome, ad esempio, con tosse e flessione.

Sintomi di disfagia correlati alla deglutizione

Il sintomo di disfagia della deglutizione più comune è la sensazione che il cibo ingerito si attacchi, nella parte inferiore del collo o nel torace.

Con problemi neurologici, potrebbe esserci difficoltà a iniziare la deglutizione perché il cibo non può essere spinto dalla lingua nella gola.

Gli anziani con la dentiera potrebbero non masticare bene il cibo e quindi ingerire grossi pezzi di cibo solido che si incastrano.

Disfagia è il termine medico per il sintomo di difficoltà a deglutire, derivato dalle parole latine e greche che significano difficoltà a mangiare.

L'ingestione è un'azione complessa.

Data la sua complessità, non sorprende che la deglutizione, a partire dalla contrazione della faringe superiore, sia stata "automatizzata", il che significa che non è necessario alcun pensiero per la deglutizione una volta iniziata la deglutizione. La deglutizione è controllata da riflessi automatici che coinvolgono i nervi all'interno della faringe e dell'esofago, nonché un centro di deglutizione nel cervello che è collegato alla faringe e all'esofago dai nervi. (Un riflesso è un meccanismo utilizzato per controllare molti organi. I riflessi richiedono nervi all'interno di un organo come l'esofago per percepire cosa sta accadendo in quell'organo e per inviare le informazioni ad altri nervi nella parete dell'organo o all'esterno dell'organo . L'informazione viene elaborata in questi altri nervi e vengono determinate le risposte appropriate alle condizioni dell'organo. Quindi, altri nervi ancora inviano messaggi dai nervi di elaborazione all'organo per controllare la funzione dell'organo, ad esempio la contrazione di i muscoli dell'organo. Nel caso della deglutizione, l'elaborazione dei riflessi si verifica principalmente nei nervi all'interno della parete della faringe e dell'esofago, nonché nel cervello.)

La complessità della deglutizione spiega anche perché ci sono così tante cause di disfagia. Possono verificarsi problemi con:

I problemi possono risiedere all'interno della faringe o dell'esofago, ad esempio, con il restringimento fisico della faringe o dell'esofago. La disfagia può anche essere dovuta a malattie dei muscoli o dei nervi che controllano i muscoli della faringe e dell'esofago o danni al centro di deglutizione nel cervello. Infine, la faringe e il terzo superiore dell'esofago contengono muscoli che sono gli stessi che utilizziamo volontariamente (come i muscoli delle braccia) chiamati muscolo scheletrico. I due terzi inferiori dell'esofago sono composti da un diverso tipo di muscolo noto come muscolatura liscia. Pertanto, le malattie che colpiscono principalmente il muscolo scheletrico o la muscolatura liscia nel corpo possono colpire la faringe e l'esofago, aggiungendo ulteriori possibilità alle cause della disfagia.

Ci sono due sintomi che sono spesso considerati problemi di deglutizione (disfagia) che probabilmente non lo sono. Questi sintomi sono odinofagia e sensazione globus.

Odinofagia significa deglutizione dolorosa. A volte non è facile per gli individui distinguere tra odinofagia e disfagia. Ad esempio, il cibo che si attacca all'esofago spesso è doloroso. Questa è disfagia o odinofagia o entrambe? Tecnicamente è disfagia, ma gli individui possono descriverla come una deglutizione dolorosa (cioè odinofagia). Inoltre, i pazienti con malattia da reflusso gastroesofageo (GERD) possono descrivere la disfagia quando ciò che realmente hanno è l'odinofagia. Il dolore che provano dopo la deglutizione si risolve quando l'infiammazione della GERD viene trattata e scompare ed è presumibilmente dovuto al dolore causato dal passaggio del cibo attraverso la porzione infiammata dell'esofago.

L'odinofagia può verificarsi anche con altre condizioni associate all'infiammazione dell'esofago, ad esempio infezioni virali e fungine. È importante distinguere tra disfagia e odinofagia perché le cause di ciascuna possono essere molto diverse.

Una sensazione globus si riferisce alla sensazione che ci sia un nodo alla gola. Il nodulo può essere presente continuamente o solo durante la deglutizione. Le cause di una sensazione globus sono varie e spesso non si trova alcuna causa. La sensazione del globo è stata attribuita in vari modi alla funzione anormale dei nervi o dei muscoli della faringe e della GERD. La sensazione del globo di solito è descritta chiaramente dagli individui e raramente provoca confusione con vera disfagia.

Come discusso in precedenza, ci sono molte cause di disfagia. Per comodità, le cause di disfagia possono essere classificate in due gruppi;

Le cause possono anche essere classificate in modo diverso in diversi gruppi.

Con problemi neurologici, potrebbe esserci difficoltà a iniziare la deglutizione perché il bolo non può essere spinto dalla lingua nella gola. Gli anziani con la dentiera potrebbero non masticare bene il cibo e quindi ingerire grossi pezzi di cibo solido che si incastrano. (Tuttavia, questo di solito si verifica quando c'è un problema aggiuntivo all'interno della faringe o dell'esofago come una stenosi.)

Il sintomo di disfagia della deglutizione più comune, tuttavia, è la sensazione che il cibo ingerito si attacchi, nella parte inferiore del collo o nel torace. Se il cibo si attacca alla gola, potrebbe esserci tosse o soffocamento con espettorazione del cibo ingerito. Se il cibo entra nella laringe, si provocheranno tosse e soffocamento più gravi. Se il palato molle non funziona e non sigilla adeguatamente i passaggi nasali, il cibo, in particolare i liquidi, possono rigurgitare nel naso con la deglutizione. A volte, il cibo può risalire in bocca subito dopo essere stato ingerito.

Il cibo che si attacca nell'esofago può rimanere lì per periodi di tempo prolungati. Ciò può creare una sensazione di riempimento del torace man mano che si mangia più cibo e portare un individuo a dover smettere di mangiare e possibilmente bere liquidi nel tentativo di lavare il cibo. L'impossibilità di mangiare grandi quantità di cibo può portare alla perdita di peso. Inoltre, il cibo che rimane nell'esofago può rigurgitare dall'esofago durante la notte mentre l'individuo dorme e l'individuo potrebbe essere svegliato da tosse o soffocamento nel cuore della notte, provocato dal rigurgito di cibo. Se il cibo entra nella laringe, nella trachea e/o nei polmoni, può provocare episodi di asma e persino portare a infezioni dei polmoni e polmonite da aspirazione. La polmonite ricorrente può causare lesioni gravi, permanenti e progressive ai polmoni. Occasionalmente, gli individui non vengono svegliati dal sonno dal cibo rigurgitato, ma si svegliano al mattino per trovare cibo rigurgitato sul cuscino.

Gli individui che trattengono il cibo nell'esofago possono lamentarsi di sintomi simili al bruciore di stomaco (GERD). I loro sintomi possono effettivamente essere dovuti a GERD, ma sono più probabilmente dovuti al cibo trattenuto e non rispondono bene al trattamento per GERD.

Con i disturbi della motilità spastica, gli individui possono sviluppare episodi di dolore toracico che possono essere così gravi da simulare un infarto e indurre gli individui a recarsi al pronto soccorso. La causa del dolore con i disturbi esofagei spastici non è chiara sebbene la teoria principale sia che sia dovuto allo spasmo dei muscoli esofagei.

Odinofagia e sensazione di globo. La difficoltà occasionale nel distinguere la disfagia dall'odinofagia è già stata discussa, così come la differenza tra disfagia e sensazione di globo.

Fistola tracheo-esofagea. Un disturbo che può essere confuso con la disfagia è una fistola tracheo-esofagea. Una fistola tracheo-esofagea è una comunicazione aperta tra l'esofago e la trachea che spesso si sviluppa a causa di tumori dell'esofago ma che può verificarsi anche come difetto congenito (congenito). Il cibo ingerito può provocare una tosse che imita la tosse a causa di una disfunzione dei muscoli della faringe che permette al cibo di entrare nella laringe; tuttavia, nel caso di una fistola, la tosse è dovuta al passaggio del cibo dall'esofago attraverso la fistola e nella trachea.

Sindrome da ruminazione. La sindrome da ruminazione è una sindrome in cui il cibo rigurgita facilmente in bocca dopo che un pasto è stato completato. Di solito si verifica nelle donne più giovani e plausibilmente potrebbe essere confuso con la disfagia. Tuttavia, non si ha la sensazione che il cibo si attacchi dopo la deglutizione.

Malattia da reflusso gastroesofageo (GERD). Le persone con GERD più grave possono avere rigurgito di cibo dallo stomaco nell'esofago o nella bocca, in particolare quando le attività aumentano la pressione nell'addome, ad esempio con la tosse e il piegamento. Il rigurgito può verificarsi anche di notte mentre le persone con GERD dormono come in quelle con disturbi della deglutizione che hanno il cibo raccolto nell'esofago.

Malattie cardiache. I disturbi della motilità spastica che causano la disfagia possono essere associati a dolore toracico spontaneo, cioè dolore toracico non associato alla deglutizione. Nonostante la presenza di disfagia, il dolore toracico spontaneo deve sempre essere considerato dovuto a malattie cardiache fino a quando le malattie cardiache non sono state escluse come causa del dolore toracico. Pertanto, è importante testare attentamente le malattie cardiache prima di considerare l'esofago come la causa del dolore toracico quando un paziente con disfagia lamenta episodi di dolore toracico spontaneo.

La storia di un individuo con disfagia spesso fornisce indizi importanti sulla causa alla base della disfagia.

La natura del sintomo o dei sintomi fornisce gli indizi più importanti sulla causa della disfagia. La deglutizione che è difficile da avviare o che porta a rigurgito nasale, tosse o soffocamento è molto probabilmente dovuta a un problema orale o faringeo. La deglutizione che provoca la sensazione di cibo che si attacca al petto (esofago) è molto probabilmente dovuta a un problema esofageo.

La disfagia che progredisce rapidamente nell'arco di settimane o pochi mesi suggerisce un tumore maligno. La disfagia per il solo cibo solido suggerisce un'ostruzione fisica al passaggio del cibo, mentre la disfagia sia per il cibo solido che liquido è più probabile che sia causata da una malattia della muscolatura liscia dell'esofago. È inoltre più probabile che i sintomi intermittenti siano causati da malattie della muscolatura liscia rispetto all'ostruzione dell'esofago poiché la disfunzione muscolare è spesso intermittente.

Anche le malattie preesistenti forniscono indizi. Quelli con malattie del muscolo scheletrico (ad esempio, polimiosite), del cervello (più comunemente ictus) o del sistema nervoso hanno maggiori probabilità di avere disfagia sulla base della disfunzione dei muscoli e dei nervi orofaringei. Le persone con malattie vascolari del collagene, ad esempio la sclerodermia, hanno maggiori probabilità di avere problemi con i muscoli esofagei, in particolare la peristalsi inefficace.

I pazienti con una storia di GERD hanno maggiori probabilità di avere stenosi esofagee come causa della loro disfagia, sebbene circa il 20% dei pazienti con stenosi abbia sintomi minimi o assenti di GERD prima dell'inizio della disfagia. Si ritiene che il reflusso che si verifica di notte sia più dannoso per l'esofago. C'è anche un rischio maggiore di cancro esofageo tra gli individui con GERD di lunga data.

La perdita di peso può essere un segno di disfagia grave o di un tumore maligno. Più spesso della perdita di peso, le persone descrivono un cambiamento nel loro schema alimentare - morsi più piccoli, masticazione aggiuntiva - che prolunga i pasti in modo che siano gli ultimi a tavola a finire di mangiare. Quest'ultimo pattern, se presente per un periodo di tempo prolungato, suggerisce una causa non maligna, relativamente stabile o lentamente progressiva per la disfagia. Episodi di dolore toracico non dovuti a malattie cardiache suggeriscono malattie muscolari dell'esofago. La nascita e la residenza nell'America centrale o meridionale sono associate alla malattia di Chagas.

L'esame obiettivo ha un valore limitato nel suggerire le cause della disfagia. Anomalie dell'esame neurologico suggeriscono malattie neurologiche o muscolari. Osservando un individuo che deglutisce, si può determinare se c'è difficoltà nell'iniziare la deglutizione, segno di una malattia neurologica. I tumori del collo suggeriscono la possibilità di compressione della faringe. Una trachea che non può essere spostata da un lato all'altro con la mano suggerisce un tumore nella parte inferiore del torace che ha intrappolato la trachea e forse l'esofago. L'osservazione di atrofia (ridotte dimensioni) o fasiculature della lingua (tremori fini) suggerisce anche malattie del sistema nervoso o del muscolo scheletrico.

Endoscopia. L'endoscopia prevede l'inserimento di un tubo flessibile lungo (un metro con una luce e una telecamera all'estremità attraverso la bocca, la faringe, l'esofago e nello stomaco. Il rivestimento della faringe e dell'esofago può essere valutato visivamente e si possono ottenere biopsie (piccoli pezzi di tessuto) per l'esame al microscopio o per colture batteriche o virali.

L'endoscopia è un mezzo eccellente per diagnosticare tumori, stenosi e anelli di Schatzki, nonché infezioni dell'esofago. È anche molto buono per la diagnosi dei diverticoli dell'esofago medio e inferiore, ma scarso per la diagnosi dei diverticoli dell'esofago superiore (diverticolo di Zenker).

È possibile osservare anomalie della contrazione muscolare esofagea, ma la manometria esofagea è un test molto più adatto per valutare la funzione dei muscoli esofagei. Resistance passing the endoscope through the lower esophageal sphincter combined with a lack of esophageal contractions is a fairly reliable sign of achalasia or Chagas disease (due to the inability of the lower esophageal sphincter to relax), but it is important when there is resistance to exclude the presence of a stricture or cancer which also can cause resistance. Finally, there is a characteristic appearance of the esophageal lining when infiltrated with eosinophils that strongly suggests the presence of eosinophilic esophagitis.

X-rays. There are two different types of X-rays that can be done to diagnose the cause of dysphagia. The barium swallow or esophagram is the simplest type. For the barium swallow, mouthfuls of barium are swallowed, and X-ray films are taken of the esophagus at several points in time while the bolus of barium traverses the esophagus. The barium swallow is excellent for diagnosing moderate-to-severe external compression, tumors, and strictures of the esophagus. Occasionally, however, Schatzki's rings can be missed.

Another type of X-ray study that can be done to evaluate swallowing is the video esophagram or video swallow, sometimes called a video-fluoroscopic swallowing study. For the video swallow, instead of several static X-ray images of the bolus traversing the esophagus, a video X-ray is taken. The video study can be reviewed frame by frame and is able to show much more than the barium swallow. This usually is not important for diagnosing tumors or strictures, which are well seen on barium swallow, but it is more effective for suggesting problems with the contraction of the muscles of the esophagus and pharynx (though esophageal manometry, discussed later, is still better for studying contraction), milder external compression of the esophagus, and Schatzki's rings. The video study can be extended to include the pharynx where it is the best method for demonstrating osteophytes, cricopharyngeal bars, and Zenker's diverticuli. A modified barium swallow is a version of the test evaluating the oropharyngeal phases of swallowing. A speech pathologist is usually involved with the evaluation to determine subtle sequence and phase abnormalities.

The video swallow also is excellent for diagnosing penetration of barium (the equivalent of food) into the larynx and trachea due to neurological and muscular problems of the pharynx that may be causing coughing or choking after swallowing food.

Esophageal manometry. Esophageal manometry, also known as esophageal motility testing, is a means to evaluate the function of pharyngeal and esophageal muscles. For manometry, a thin, flexible catheter is passed through the nose and pharynx and into the esophagus. The catheter is able to sense pressure at multiple locations along its length in both the pharynx and the esophagus. When the pharyngeal and esophageal muscles contract, they generate a pressure on the catheter which is sensed, measured and recorded from each location. The magnitude of the pressure at each pressure-sensing location and the timing of the increases in pressure at each location in relation to other locations give an accurate picture of how the muscles of the pharynx and esophagus are contracting.

The value of manometry is in diagnosing and differentiating among diseases of the muscle or the nerves controlling the muscles that result in muscle dysfunction of the pharynx and esophagus. Thus, it is useful for diagnosing the swallowing dysfunction caused by diseases of the brain, skeletal muscle of the pharynx, and smooth muscle of the esophagus.

Esophageal impedence. Esophageal impedence testing utilizes catheters similar to those used for esophageal manometry. Impedence testing, however, senses the flow of the bolus through the esophagus. Thus, it is possible to determine how well the bolus is traversing the esophagus and correlate the movement with concomitantly recorded esophageal pressures determined by manometry. (It also can be used to sense reflux of stomach contents into the esophagus among patients with GERD.) Multiple sites along the length of the esophagus can be tested to assess the movement of the bolus and presence of reflux, including how high up it extends.

Esophageal acid testing. Esophageal acid testing is not a test that directly diagnoses diseases of the esophagus. Rather, it is a method for determining whether or not there is reflux of acid from the stomach into the esophagus, a cause of the most common esophageal problem leading to dysphagia, esophageal stricture. For acid testing, a thin catheter is inserted through the nose, down the throat, and into the esophagus. At the tip of the catheter and placed just above the junction of the esophagus with the stomach is an acid-sensing probe. The catheter coming out of the nose passes back over the ear and down to the waist where it is attached to a recorder. Each time acid refluxes (regurgitates) from the stomach and into the esophagus it hits the probe, and the reflux of acid is recorded by the recorder. At the end of a prolonged period, usually 24 hours, the catheter is removed and the information from the recorder is downloaded into a computer for analysis. Most people have a small amount of reflux of acid, but individuals with GERD have more. Thus, acid testing can determine if GERD is likely to be the cause of the esophageal problem such as a stricture, as well as if treatment of GERD is adequate by showing the amount of acid that refluxes during treatment is normal.

An alternative method of esophageal acid testing uses a small capsule containing an acid-sensing probe that is attached to the esophageal lining just above the junction of the esophagus with the stomach. The capsule wirelessly transmits the presence of episodes of acid regurgitation to a receiver carried on the chest. The capsule records for two or three days and later is shed into the esophagus and passes out of the body in the stool.

Other tests The diagnosis of muscular dystrophies and metabolic myopathies usually involves a combination of tests including blood tests that can suggest muscle injury, electromyograms to determine if nerves and muscles are working normally, biopsies of muscles, and genetic testing.

The treatment of dysphagia varies and depends on the cause of the dysphagia. One option for supporting patients either transiently or long-term until the cause of the dysphagia resolves is a feeding tube. The tube for feeding may be passed nasally into the stomach or through the abdominal wall into the stomach or small intestine. Once oral feeding resumes, the tube can be removed.

Treatment for obstruction of the pharynx or esophagus requires removal of the obstruction.

Tumors usually are removed surgically although occasionally they can be removed endoscopically, totally or partially. Radiation therapy and chemotherapy also may be used particularly for malignant tumors of the pharynx and its surrounding tissues. If malignant tumors of the esophagus cannot be easily removed or the tumor has spread and survival will be limited, swallowing can be improved by placing stents within the esophagus across the area of obstruction. Occasionally, obstructing tumors can be dilated the same way as strictures. (See below.)

Strictures and Schatzki's rings usually are treated with endoscopic dilation, a procedure in which the narrowed area is stretched either by a long, semi-rigid tube passed through the mouth or a balloon that is blown up inside the esophagus.

The most common infiltrating disease causing dysphagia is eosinophilic esophagitis which usually is successfully treated with swallowed corticosteroids. The role of food allergy as a cause of eosinophilic esophagitis is debated; however, there are reports of using elimination diets to identify specific foods that are associated with allergy. Elimination of these foods has been reported to prevent or reverse the infiltration of the esophagus with eosinophils, particularly in children.

Diverticuli of the pharynx and esophagus usually are treated surgically by excising them. Occasionally they can be treated endoscopically. Cricopharyngeal bars are treated surgically by cutting the thickened muscle. Osteophytes also can be removed surgically.

Congenital abnormalities of the esophagus usually are treated surgically soon after birth so that oral feeding can resume.

As previously discussed, strokes are the most common disease of the brain to cause dysphagia. Dysphagia usually is at its worst immediately after the stroke, and often the dysphagia improves with time and even may disappear. If it does not disappear, swallowing is evaluated, usually with a video swallowing study. The exact abnormality of function can be defined and different maneuvers can be performed to see if they can counter the effects of the dysfunction. For example, in some patients it is possible to prevent aspiration of food by turning the head to the side when swallowing or by drinking thickened liquids (since thin liquids is the food most likely to be aspirated).

Tumors of the brain, in some cases, can be removed surgically; however, it is unlikely that surgery will reverse the dysphagia. Parkinson's disease and multiple sclerosis can be treated with drugs and may be useful in patients with dysphagia.

Achalasia is treated like a stricture of the esophagus with dilation, usually with a balloon. A second option is surgical treatment in which the muscle of the lower esophageal sphincter is cut (a myotomy) in order to reduce the pressure and obstruction caused by the non-relaxing sphincter. Drugs that relax the sphincter usually have little or a transient effect and are useful only when achalasia is mild.

An option for individuals who are at high risk for surgery or balloon dilation is injection of botulinin toxin into the sphincter. The toxin paralyzes the muscle of the sphincter and causes the pressure within the sphincter to decrease. The effects of botulinin toxin are transient, however, and repeated injections usually are necessary. It is best to treat achalasia early before the obstruction causes the esophagus to enlarge (dilate) which can lead to additional problems such as food collecting above the sphincter with regurgitation and aspiration.

In other spastic motility disorders, several drugs may be tried, including anti-cholinergic medications, peppermint, nitroglycerin, and calcium channel blockers, but the effectiveness of these drugs is not clear and studies with them are nonexistent or limited.

For patients with severe and uncontrollable symptoms of pain and/or dysphagia, a surgical procedure called a long myotomy occasionally is performed. A long myotomy is similar to the surgical treatment for achalasia but the cut in the muscle is extended up along the body of the esophagus for a variable distance in an attempt to reduce pressures and obstruction to the bolus.

There is no treatment for ineffective peristalsis, and individuals must change their eating habits. Fortunately, ineffective peristalsis infrequently causes severe dysphagia by itself. When moderate or severe dysphagia is associated with ineffective peristalsis it is important to be certain that there is no additional obstruction of the esophagus, for example, by a stricture due to GERD, that is adding to the effects of reduced muscle function and making dysphagia worse than the ineffective peristalsis alone. Most causes of obstruction can be treated.

There are effective drug therapies for polymyositis and myasthenia gravis that should also improve associated dysphagia. Treatment of the muscular dystrophies is primarily directed at preventing deformities of the joints that commonly occur and lead to immobility, but there are no therapies that affect the dysphagia. Corticosteroids and drugs that suppress immunity sometimes are used to treat some of the muscular dystrophies, but their effectiveness has not been demonstrated.

There is no treatment for the metabolic myopathies other than changes in lifestyle and diet.

Diseases that reduce the production of saliva can be treated with artificial saliva or over-the-counter and prescription drugs that stimulate the production of saliva.

There is no treatment for Alzheimer's disease.

With the exception of dysphagia caused by stroke for which there can be marked improvement, dysphagia from other causes is stable or progressive, and the prognosis depends on the underlying cause, its tendency to progress, the availability of therapy, and the response to therapy.

Recent developments in the diagnostic arena are beginning to bring new insights into esophageal function, specifically, high resolution and 3D manometry, and endoscopic ultrasound.

High resolution and 3D manometry

High resolution and 3D manometry are extensions of standard manometry that utilize similar catheters. The difference is that the pressure-sensing locations on the catheters are very close together and ring the catheter. Recording of pressures from so many locations gives an extremely detailed picture of how esophageal muscle is contracting. The primary value of these diagnostic procedures is that they "integrate" the activities of the esophagus so that the overall pattern of swallowing can be recognized, which is particularly important in complex motility disorders. In addition, their added detail allows the recognition of subtle abnormalities and hopefully will be able to help define the clinical importance of subtle abnormalities of muscle contraction associated with lesser degrees of dysphagia.

Endoscopic ultrasonography has been available for many years but has recently been applied to the evaluation of esophageal muscle diseases. Ultrasound uses sound waves to penetrate tissues. The sound waves are reflected by the tissues and structures they encounter, and, when analyzed, the reflections give information about the tissues and structures from which they are reflected. In the esophagus, endoscopic ultrasonography has been used to determine the extent of penetration of tumors into the esophageal wall and the presence of metastases to adjacent lymph nodes. More recently, endoscopic ultrasonography has been used to obtain a detailed look at the muscles of the esophagus. What has been found is that in some disorders, particularly the spastic motility disorders, the muscle of the esophagus is thickened. Moreover, thickening of the muscle sometimes can be recognized only by ultrasonography even when spastic abnormalities are not seen with manometry. The exact role of endoscopic ultrasonography has not yet been determined but is an exciting area for future research.

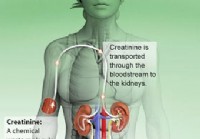

Esame del sangue della creatinina (livelli normali, bassi, alti)

Esame del sangue della creatinina (livelli normali, bassi, alti)

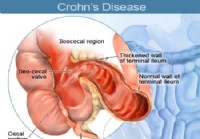

Domande frequenti sulla malattia di Crohn

Domande frequenti sulla malattia di Crohn

La melma di pesce potrebbe essere una potenziale fonte di antibiotici trova studio

La melma di pesce potrebbe essere una potenziale fonte di antibiotici trova studio

L'arte di cucinare e mangiare il carciofo

L'arte di cucinare e mangiare il carciofo

Modi per aiutare il bambino a sviluppare buone abitudini alimentari

Modi per aiutare il bambino a sviluppare buone abitudini alimentari

Integratori e microbioma intestinale

Integratori e microbioma intestinale

Come la medicina funzionale può curare l'eczema

Oggi sono entusiasta di condividere un post importante di una delle praticanti che ammiro:la dott.ssa Stephanie Davis. Stephanie è una dottoressa in medicina chiropratica che ha studiato a fondo lapp

Come la medicina funzionale può curare l'eczema

Oggi sono entusiasta di condividere un post importante di una delle praticanti che ammiro:la dott.ssa Stephanie Davis. Stephanie è una dottoressa in medicina chiropratica che ha studiato a fondo lapp

La notevole remissione della colite ulcerosa di Dawn

Come esseri umani, alla maggior parte di noi non piace sentirsi dire Fai questo o altro! (Penso che sia abbastanza ovvio il motivo.) Non riesco nemmeno a contare il numero di volte in cui mi è stato

La notevole remissione della colite ulcerosa di Dawn

Come esseri umani, alla maggior parte di noi non piace sentirsi dire Fai questo o altro! (Penso che sia abbastanza ovvio il motivo.) Non riesco nemmeno a contare il numero di volte in cui mi è stato

Cosa ferma la diarrea velocemente?

Diarrea o feci molli possono essere causate da infezioni, parassiti, alcuni farmaci, malattie intestinali, intolleranze alimentari, ormoni disturbi, cancro intestinale o intolleranza al lattosio. Puoi

Cosa ferma la diarrea velocemente?

Diarrea o feci molli possono essere causate da infezioni, parassiti, alcuni farmaci, malattie intestinali, intolleranze alimentari, ormoni disturbi, cancro intestinale o intolleranza al lattosio. Puoi