Las personas con ERGE más grave pueden tener comida regurgitada desde el estómago hacia el esófago o la boca, especialmente cuando las actividades aumentan la presión en el abdomen, por ejemplo, al toser y doblarse.

Las personas con ERGE más grave pueden tener comida regurgitada desde el estómago hacia el esófago o la boca, especialmente cuando las actividades aumentan la presión en el abdomen, por ejemplo, al toser y doblarse.

Síntomas de disfagia relacionados con la deglución

El síntoma de deglución más común de la disfagia es la sensación de que los alimentos tragados se pegan, ya sea en la parte inferior del cuello o en el pecho.

Con problemas neurológicos, puede haber dificultad para iniciar una deglución porque la lengua no puede impulsar la comida hacia la garganta.

Es posible que las personas mayores con prótesis dentales no mastiquen bien los alimentos y, por lo tanto, traguen grandes trozos de alimentos sólidos que se atascan.

Disfagia es el término médico para el síntoma de dificultad para tragar, derivado de las palabras latinas y griegas que significan dificultad para comer.

Tragar es una acción compleja.

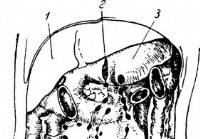

Teniendo en cuenta su complejidad, no es de extrañar que la deglución, comenzando con la contracción de la faringe superior, se haya "automatizado", lo que significa que no se requiere pensar para tragar una vez que se inicia la deglución. La deglución está controlada por reflejos automáticos que involucran nervios dentro de la faringe y el esófago, así como un centro de deglución en el cerebro que está conectado a la faringe y el esófago por medio de nervios. (Un reflejo es un mecanismo que se usa para controlar muchos órganos. Los reflejos requieren nervios dentro de un órgano como el esófago para sentir lo que está sucediendo en ese órgano y enviar la información a otros nervios en la pared del órgano o fuera del órgano. . La información se procesa en estos otros nervios y se determinan las respuestas adecuadas a las condiciones del órgano. Luego, otros nervios envían mensajes desde los nervios de procesamiento de regreso al órgano para controlar la función del órgano, por ejemplo, la contracción de los músculos del órgano. En el caso de la deglución, el procesamiento de los reflejos ocurre principalmente en los nervios dentro de la pared de la faringe y el esófago, así como en el cerebro).

La complejidad de la deglución también explica por qué hay tantas causas de disfagia. Pueden ocurrir problemas con:

Los problemas pueden estar dentro de la faringe o el esófago, por ejemplo, con el estrechamiento físico de la faringe o el esófago. La disfagia también puede deberse a enfermedades de los músculos o de los nervios que controlan los músculos de la faringe y el esófago o al daño en el centro de deglución del cerebro. Finalmente, la faringe y el tercio superior del esófago contienen un músculo que es el mismo que los músculos que usamos voluntariamente (como los músculos de nuestros brazos) llamado músculo esquelético. Los dos tercios inferiores del esófago están compuestos por un tipo diferente de músculo conocido como músculo liso. Por lo tanto, las enfermedades que afectan principalmente al músculo esquelético o al músculo liso del cuerpo pueden afectar la faringe y el esófago, lo que agrega posibilidades adicionales a las causas de la disfagia.

Hay dos síntomas que a menudo se consideran problemas para tragar (disfagia) que probablemente no lo sean. Estos síntomas son odinofagia y sensación de globo.

Odinofagia significa tragar con dolor. A veces, no es fácil para las personas distinguir entre odinofagia y disfagia. Por ejemplo, la comida que se pega en el esófago suele ser dolorosa. ¿Esto es disfagia, odinofagia o ambas? Técnicamente es disfagia, pero las personas pueden describirlo como dolor al tragar (es decir, odinofagia). Además, los pacientes con enfermedad por reflujo gastroesofágico (ERGE) pueden describir disfagia cuando en realidad lo que tienen es odinofagia. El dolor que sienten después de tragar se resuelve cuando la inflamación de la ERGE se trata y desaparece, y presumiblemente se debe al dolor causado por el paso de los alimentos a través de la parte inflamada del esófago.

La odinofagia también puede ocurrir con otras afecciones asociadas con la inflamación del esófago, por ejemplo, infecciones virales y fúngicas. Es importante distinguir entre disfagia y odinofagia porque las causas de cada una pueden ser muy diferentes.

Una sensación de globo se refiere a la sensación de que hay un nudo en la garganta. El bulto puede estar presente continuamente o solo al tragar. Las causas de una sensación de globo son variadas y con frecuencia no se encuentra la causa. La sensación de globo se ha atribuido de diversas formas a la función anormal de los nervios o músculos de la faringe y la ERGE. La sensación de globo por lo general se describe claramente por los individuos y con poca frecuencia causa confusión con la verdadera disfagia.

Como se discutió anteriormente, hay muchas causas de disfagia. Por conveniencia, las causas de la disfagia se pueden clasificar en dos grupos;

Las causas también se pueden clasificar de forma diferente en varios grupos.

Con problemas neurológicos, puede haber dificultad para iniciar una deglución porque la lengua no puede impulsar el bolo hacia la garganta. Es posible que las personas mayores con prótesis dentales no mastiquen bien los alimentos y, por lo tanto, traguen grandes trozos de alimentos sólidos que se atascan. (Sin embargo, esto generalmente ocurre cuando hay un problema adicional dentro de la faringe o el esófago, como una estenosis).

Sin embargo, el síntoma de deglución más común de la disfagia es la sensación de que los alimentos tragados se pegan, ya sea en la parte inferior del cuello o en el pecho. Si la comida se pega en la garganta, puede haber tos o ahogo con expectoración de la comida tragada. Si la comida ingresa a la laringe, se provocará una tos más severa y asfixia. Si el paladar blando no funciona y no sella correctamente las fosas nasales, los alimentos, en particular los líquidos, pueden regurgitar en la nariz al tragar. A veces, la comida puede regresar a la boca inmediatamente después de tragarla.

Los alimentos que se pegan en el esófago pueden permanecer allí por períodos prolongados de tiempo. Esto puede crear una sensación de que el tórax se llena a medida que se come más comida y hacer que una persona deba dejar de comer y posiblemente beber líquidos en un intento de tragar la comida. La incapacidad de comer grandes cantidades de alimentos puede conducir a la pérdida de peso. Además, la comida que permanece en el esófago puede regurgitar desde el esófago durante la noche mientras el individuo duerme, y el individuo puede despertarse tosiendo o asfixiándose en medio de la noche provocado por la regurgitación de alimentos. Si el alimento entra en la laringe, la tráquea y/o los pulmones, puede provocar episodios de asma e incluso provocar una infección de los pulmones y una neumonía por aspiración. La neumonía recurrente puede provocar lesiones graves, permanentes y progresivas en los pulmones. Ocasionalmente, las personas no se despiertan del sueño por la comida regurgitada, sino que se despiertan por la mañana para encontrar comida regurgitada en su almohada.

Las personas que retienen alimentos en el esófago pueden quejarse de síntomas similares a los de la acidez estomacal (ERGE). De hecho, sus síntomas pueden deberse a la ERGE, pero es más probable que se deban a la retención de alimentos y que no respondan bien al tratamiento de la ERGE.

Con los trastornos de la motilidad espástica, las personas pueden desarrollar episodios de dolor torácico que pueden ser tan graves como para simular un ataque cardíaco y hacer que las personas acudan a la sala de emergencias. La causa del dolor con los trastornos esofágicos espásticos no está clara, aunque la teoría principal es que se debe a un espasmo de los músculos esofágicos.

Odinofagia y sensación de globo. Ya se ha comentado la dificultad ocasional para distinguir la disfagia de la odinofagia, así como la diferencia entre disfagia y sensación de globo.

Fístula traqueoesofágica. Un trastorno que puede confundirse con disfagia es una fístula traqueoesofágica. Una fístula traqueoesofágica es una comunicación abierta entre el esófago y la tráquea que a menudo se desarrolla debido a cánceres de esófago pero que también puede ocurrir como un defecto de nacimiento congénito (innato). Los alimentos ingeridos pueden provocar tos que imita la tos debido a la disfunción de los músculos de la faringe que permiten que los alimentos entren en la laringe; sin embargo, en el caso de una fístula, la tos se debe al paso de alimentos desde el esófago a través de la fístula hacia la tráquea.

Síndrome de rumiación. El síndrome de rumiación es un síndrome en el que la comida regurgita sin esfuerzo en la boca después de que se completa una comida. Por lo general, ocurre en mujeres más jóvenes y posiblemente podría confundirse con disfagia. Sin embargo, no hay sensación de que la comida se pegue después de tragarla.

Enfermedad por reflujo gastroesofágico (ERGE). Las personas con ERGE más grave pueden tener regurgitación de alimentos desde el estómago hacia el esófago o la boca, especialmente cuando las actividades aumentan la presión en el abdomen, por ejemplo, al toser y agacharse. La regurgitación también puede ocurrir por la noche mientras las personas con ERGE duermen, como en aquellas con trastornos de la deglución que tienen comida acumulada en el esófago.

Enfermedad del corazón. Los trastornos de la motilidad espástica que causan disfagia pueden estar asociados con dolor torácico espontáneo, es decir, dolor torácico no asociado con la deglución. A pesar de la presencia de disfagia, siempre se debe suponer que el dolor torácico espontáneo se debe a una enfermedad cardíaca hasta que se haya excluido la enfermedad cardíaca como causa del dolor torácico. Por lo tanto, es importante realizar pruebas cuidadosas para detectar enfermedades cardíacas antes de considerar el esófago como la causa del dolor torácico cuando un paciente con disfagia se queja de episodios de dolor torácico espontáneo.

El historial de una persona con disfagia a menudo proporciona pistas importantes sobre la causa subyacente de la disfagia.

La naturaleza del síntoma o síntomas proporciona las pistas más importantes sobre la causa de la disfagia. La deglución que es difícil de iniciar o que conduce a regurgitación nasal, tos o asfixia probablemente se deba a un problema oral o faríngeo. La deglución que da como resultado la sensación de que la comida se pega en el pecho (esófago) probablemente se deba a un problema esofágico.

La disfagia que progresa rápidamente durante semanas o algunos meses sugiere un tumor maligno. La disfagia por alimentos sólidos solo sugiere una obstrucción física al paso de los alimentos, mientras que la disfagia por alimentos sólidos y líquidos es más probable que sea causada por una enfermedad del músculo liso del esófago. Los síntomas intermitentes también tienen más probabilidades de ser causados por enfermedades del músculo liso que por obstrucción del esófago, ya que la disfunción del músculo a menudo es intermitente.

Las enfermedades preexistentes también proporcionan pistas. Las personas con enfermedades del músculo esquelético (por ejemplo, polimiositis), el cerebro (más comúnmente accidente cerebrovascular) o el sistema nervioso tienen más probabilidades de tener disfagia sobre la base de la disfunción de los músculos y nervios orofaríngeos. Las personas con enfermedades vasculares del colágeno, por ejemplo, esclerodermia, tienen más probabilidades de tener problemas con los músculos del esófago, especialmente peristalsis ineficaz.

Los pacientes con antecedentes de ERGE tienen más probabilidades de tener estenosis esofágicas como causa de su disfagia, aunque alrededor del 20 % de los pacientes con estenosis tienen síntomas mínimos o nulos de ERGE antes del inicio de la disfagia. Se cree que el reflujo que ocurre por la noche es más perjudicial para el esófago. También existe un mayor riesgo de cáncer de esófago entre las personas con ERGE de larga data.

La pérdida de peso puede ser un signo de disfagia grave o de un tumor maligno. Más a menudo que perder peso, las personas describen un cambio en su patrón de alimentación (bocados más pequeños, masticación adicional) que prolongan las comidas para que sean los últimos en terminar de comer en la mesa. Este último patrón, si está presente durante un período prolongado de tiempo, sugiere una causa no maligna, relativamente estable o lentamente progresiva de la disfagia. Los episodios de dolor torácico que no se deben a una enfermedad cardíaca sugieren enfermedades musculares del esófago. El nacimiento y la residencia en América Central o del Sur están asociados con la enfermedad de Chagas.

El examen físico tiene un valor limitado para sugerir las causas de la disfagia. Las anormalidades del examen neurológico sugieren enfermedades neurológicas o musculares. Al observar la deglución de un individuo, se puede determinar si hay dificultad para iniciar la deglución, un signo de enfermedad neurológica. Los tumores en el cuello sugieren la posibilidad de compresión de la faringe. Una tráquea que no se puede mover de un lado a otro con la mano sugiere un tumor en la parte inferior del tórax que ha atrapado la tráquea y posiblemente el esófago. Observar atrofia (tamaño reducido) o fasciculaciones de la lengua (temblores finos) también sugieren enfermedades del sistema nervioso o del músculo esquelético.

Endoscopia. La endoscopia implica la inserción de un tubo flexible largo (un metro) con una luz y una cámara en su extremo a través de la boca, la faringe, el esófago y el estómago. El revestimiento de la faringe y el esófago se puede evaluar visualmente y se pueden obtener biopsias (pequeños fragmentos de tejido) para examinarlos al microscopio o para cultivos bacterianos o virales.

La endoscopia es un medio excelente para diagnosticar tumores, estenosis y anillos de Schatzki, así como infecciones del esófago. También es muy bueno para diagnosticar divertículos del esófago medio e inferior, pero deficiente para diagnosticar divertículos en el esófago superior (divertículo de Zenker).

Es posible observar anomalías de la contracción muscular esofágica, pero la manometría esofágica es una prueba mucho más adecuada para evaluar la función de los músculos esofágicos. Resistance passing the endoscope through the lower esophageal sphincter combined with a lack of esophageal contractions is a fairly reliable sign of achalasia or Chagas disease (due to the inability of the lower esophageal sphincter to relax), but it is important when there is resistance to exclude the presence of a stricture or cancer which also can cause resistance. Finally, there is a characteristic appearance of the esophageal lining when infiltrated with eosinophils that strongly suggests the presence of eosinophilic esophagitis.

X-rays. There are two different types of X-rays that can be done to diagnose the cause of dysphagia. The barium swallow or esophagram is the simplest type. For the barium swallow, mouthfuls of barium are swallowed, and X-ray films are taken of the esophagus at several points in time while the bolus of barium traverses the esophagus. The barium swallow is excellent for diagnosing moderate-to-severe external compression, tumors, and strictures of the esophagus. Occasionally, however, Schatzki's rings can be missed.

Another type of X-ray study that can be done to evaluate swallowing is the video esophagram or video swallow, sometimes called a video-fluoroscopic swallowing study. For the video swallow, instead of several static X-ray images of the bolus traversing the esophagus, a video X-ray is taken. The video study can be reviewed frame by frame and is able to show much more than the barium swallow. This usually is not important for diagnosing tumors or strictures, which are well seen on barium swallow, but it is more effective for suggesting problems with the contraction of the muscles of the esophagus and pharynx (though esophageal manometry, discussed later, is still better for studying contraction), milder external compression of the esophagus, and Schatzki's rings. The video study can be extended to include the pharynx where it is the best method for demonstrating osteophytes, cricopharyngeal bars, and Zenker's diverticuli. A modified barium swallow is a version of the test evaluating the oropharyngeal phases of swallowing. A speech pathologist is usually involved with the evaluation to determine subtle sequence and phase abnormalities.

The video swallow also is excellent for diagnosing penetration of barium (the equivalent of food) into the larynx and trachea due to neurological and muscular problems of the pharynx that may be causing coughing or choking after swallowing food.

Esophageal manometry. Esophageal manometry, also known as esophageal motility testing, is a means to evaluate the function of pharyngeal and esophageal muscles. For manometry, a thin, flexible catheter is passed through the nose and pharynx and into the esophagus. The catheter is able to sense pressure at multiple locations along its length in both the pharynx and the esophagus. When the pharyngeal and esophageal muscles contract, they generate a pressure on the catheter which is sensed, measured and recorded from each location. The magnitude of the pressure at each pressure-sensing location and the timing of the increases in pressure at each location in relation to other locations give an accurate picture of how the muscles of the pharynx and esophagus are contracting.

The value of manometry is in diagnosing and differentiating among diseases of the muscle or the nerves controlling the muscles that result in muscle dysfunction of the pharynx and esophagus. Thus, it is useful for diagnosing the swallowing dysfunction caused by diseases of the brain, skeletal muscle of the pharynx, and smooth muscle of the esophagus.

Esophageal impedence. Esophageal impedence testing utilizes catheters similar to those used for esophageal manometry. Impedence testing, however, senses the flow of the bolus through the esophagus. Thus, it is possible to determine how well the bolus is traversing the esophagus and correlate the movement with concomitantly recorded esophageal pressures determined by manometry. (It also can be used to sense reflux of stomach contents into the esophagus among patients with GERD.) Multiple sites along the length of the esophagus can be tested to assess the movement of the bolus and presence of reflux, including how high up it extends.

Esophageal acid testing. Esophageal acid testing is not a test that directly diagnoses diseases of the esophagus. Rather, it is a method for determining whether or not there is reflux of acid from the stomach into the esophagus, a cause of the most common esophageal problem leading to dysphagia, esophageal stricture. For acid testing, a thin catheter is inserted through the nose, down the throat, and into the esophagus. At the tip of the catheter and placed just above the junction of the esophagus with the stomach is an acid-sensing probe. The catheter coming out of the nose passes back over the ear and down to the waist where it is attached to a recorder. Each time acid refluxes (regurgitates) from the stomach and into the esophagus it hits the probe, and the reflux of acid is recorded by the recorder. At the end of a prolonged period, usually 24 hours, the catheter is removed and the information from the recorder is downloaded into a computer for analysis. Most people have a small amount of reflux of acid, but individuals with GERD have more. Thus, acid testing can determine if GERD is likely to be the cause of the esophageal problem such as a stricture, as well as if treatment of GERD is adequate by showing the amount of acid that refluxes during treatment is normal.

An alternative method of esophageal acid testing uses a small capsule containing an acid-sensing probe that is attached to the esophageal lining just above the junction of the esophagus with the stomach. The capsule wirelessly transmits the presence of episodes of acid regurgitation to a receiver carried on the chest. The capsule records for two or three days and later is shed into the esophagus and passes out of the body in the stool.

Other tests The diagnosis of muscular dystrophies and metabolic myopathies usually involves a combination of tests including blood tests that can suggest muscle injury, electromyograms to determine if nerves and muscles are working normally, biopsies of muscles, and genetic testing.

The treatment of dysphagia varies and depends on the cause of the dysphagia. One option for supporting patients either transiently or long-term until the cause of the dysphagia resolves is a feeding tube. The tube for feeding may be passed nasally into the stomach or through the abdominal wall into the stomach or small intestine. Once oral feeding resumes, the tube can be removed.

Treatment for obstruction of the pharynx or esophagus requires removal of the obstruction.

Tumors usually are removed surgically although occasionally they can be removed endoscopically, totally or partially. Radiation therapy and chemotherapy also may be used particularly for malignant tumors of the pharynx and its surrounding tissues. If malignant tumors of the esophagus cannot be easily removed or the tumor has spread and survival will be limited, swallowing can be improved by placing stents within the esophagus across the area of obstruction. Occasionally, obstructing tumors can be dilated the same way as strictures. (See below.)

Strictures and Schatzki's rings usually are treated with endoscopic dilation, a procedure in which the narrowed area is stretched either by a long, semi-rigid tube passed through the mouth or a balloon that is blown up inside the esophagus.

The most common infiltrating disease causing dysphagia is eosinophilic esophagitis which usually is successfully treated with swallowed corticosteroids. The role of food allergy as a cause of eosinophilic esophagitis is debated; however, there are reports of using elimination diets to identify specific foods that are associated with allergy. Elimination of these foods has been reported to prevent or reverse the infiltration of the esophagus with eosinophils, particularly in children.

Diverticuli of the pharynx and esophagus usually are treated surgically by excising them. Occasionally they can be treated endoscopically. Cricopharyngeal bars are treated surgically by cutting the thickened muscle. Osteophytes also can be removed surgically.

Congenital abnormalities of the esophagus usually are treated surgically soon after birth so that oral feeding can resume.

As previously discussed, strokes are the most common disease of the brain to cause dysphagia. Dysphagia usually is at its worst immediately after the stroke, and often the dysphagia improves with time and even may disappear. If it does not disappear, swallowing is evaluated, usually with a video swallowing study. The exact abnormality of function can be defined and different maneuvers can be performed to see if they can counter the effects of the dysfunction. For example, in some patients it is possible to prevent aspiration of food by turning the head to the side when swallowing or by drinking thickened liquids (since thin liquids is the food most likely to be aspirated).

Tumors of the brain, in some cases, can be removed surgically; however, it is unlikely that surgery will reverse the dysphagia. Parkinson's disease and multiple sclerosis can be treated with drugs and may be useful in patients with dysphagia.

Achalasia is treated like a stricture of the esophagus with dilation, usually with a balloon. A second option is surgical treatment in which the muscle of the lower esophageal sphincter is cut (a myotomy) in order to reduce the pressure and obstruction caused by the non-relaxing sphincter. Drugs that relax the sphincter usually have little or a transient effect and are useful only when achalasia is mild.

An option for individuals who are at high risk for surgery or balloon dilation is injection of botulinin toxin into the sphincter. The toxin paralyzes the muscle of the sphincter and causes the pressure within the sphincter to decrease. The effects of botulinin toxin are transient, however, and repeated injections usually are necessary. It is best to treat achalasia early before the obstruction causes the esophagus to enlarge (dilate) which can lead to additional problems such as food collecting above the sphincter with regurgitation and aspiration.

In other spastic motility disorders, several drugs may be tried, including anti-cholinergic medications, peppermint, nitroglycerin, and calcium channel blockers, but the effectiveness of these drugs is not clear and studies with them are nonexistent or limited.

For patients with severe and uncontrollable symptoms of pain and/or dysphagia, a surgical procedure called a long myotomy occasionally is performed. A long myotomy is similar to the surgical treatment for achalasia but the cut in the muscle is extended up along the body of the esophagus for a variable distance in an attempt to reduce pressures and obstruction to the bolus.

There is no treatment for ineffective peristalsis, and individuals must change their eating habits. Fortunately, ineffective peristalsis infrequently causes severe dysphagia by itself. When moderate or severe dysphagia is associated with ineffective peristalsis it is important to be certain that there is no additional obstruction of the esophagus, for example, by a stricture due to GERD, that is adding to the effects of reduced muscle function and making dysphagia worse than the ineffective peristalsis alone. Most causes of obstruction can be treated.

There are effective drug therapies for polymyositis and myasthenia gravis that should also improve associated dysphagia. Treatment of the muscular dystrophies is primarily directed at preventing deformities of the joints that commonly occur and lead to immobility, but there are no therapies that affect the dysphagia. Corticosteroids and drugs that suppress immunity sometimes are used to treat some of the muscular dystrophies, but their effectiveness has not been demonstrated.

There is no treatment for the metabolic myopathies other than changes in lifestyle and diet.

Diseases that reduce the production of saliva can be treated with artificial saliva or over-the-counter and prescription drugs that stimulate the production of saliva.

There is no treatment for Alzheimer's disease.

With the exception of dysphagia caused by stroke for which there can be marked improvement, dysphagia from other causes is stable or progressive, and the prognosis depends on the underlying cause, its tendency to progress, the availability of therapy, and the response to therapy.

Recent developments in the diagnostic arena are beginning to bring new insights into esophageal function, specifically, high resolution and 3D manometry, and endoscopic ultrasound.

High resolution and 3D manometry

High resolution and 3D manometry are extensions of standard manometry that utilize similar catheters. The difference is that the pressure-sensing locations on the catheters are very close together and ring the catheter. Recording of pressures from so many locations gives an extremely detailed picture of how esophageal muscle is contracting. The primary value of these diagnostic procedures is that they "integrate" the activities of the esophagus so that the overall pattern of swallowing can be recognized, which is particularly important in complex motility disorders. In addition, their added detail allows the recognition of subtle abnormalities and hopefully will be able to help define the clinical importance of subtle abnormalities of muscle contraction associated with lesser degrees of dysphagia.

Endoscopic ultrasonography has been available for many years but has recently been applied to the evaluation of esophageal muscle diseases. Ultrasound uses sound waves to penetrate tissues. The sound waves are reflected by the tissues and structures they encounter, and, when analyzed, the reflections give information about the tissues and structures from which they are reflected. In the esophagus, endoscopic ultrasonography has been used to determine the extent of penetration of tumors into the esophageal wall and the presence of metastases to adjacent lymph nodes. More recently, endoscopic ultrasonography has been used to obtain a detailed look at the muscles of the esophagus. What has been found is that in some disorders, particularly the spastic motility disorders, the muscle of the esophagus is thickened. Moreover, thickening of the muscle sometimes can be recognized only by ultrasonography even when spastic abnormalities are not seen with manometry. The exact role of endoscopic ultrasonography has not yet been determined but is an exciting area for future research.

Diario curativo de la dieta para la SCD de Steve:semana 23:cócteles de verano legales para la SCD

Diario curativo de la dieta para la SCD de Steve:semana 23:cócteles de verano legales para la SCD

Pascado frito paleo de 5 minutos

Pascado frito paleo de 5 minutos

Hígado graso (hígado graso no alcohólico)

Hígado graso (hígado graso no alcohólico)

Linfadenitis mezenterialny aguda - Diagnóstico de abdomen agudo

Linfadenitis mezenterialny aguda - Diagnóstico de abdomen agudo

Cápsula endoscópica (cápsula endoscópica inalámbrica)

Cápsula endoscópica (cápsula endoscópica inalámbrica)

Los antioxidantes en la dieta podrían aumentar el riesgo de cáncer de intestino,

Los antioxidantes en la dieta podrían aumentar el riesgo de cáncer de intestino,

Los cambios bacterianos intestinales influyen en los resultados del tratamiento del lupus en el embarazo

El curso del embarazo como el del amor verdadero, no siempre funciona bien cuando tienes lupus, correctamente llamado lupus eritematoso sistémico (LES). Esta enfermedad autoinmune es ocasionalmente vi

Los cambios bacterianos intestinales influyen en los resultados del tratamiento del lupus en el embarazo

El curso del embarazo como el del amor verdadero, no siempre funciona bien cuando tienes lupus, correctamente llamado lupus eritematoso sistémico (LES). Esta enfermedad autoinmune es ocasionalmente vi

Remisión de Crohn

La enfermedad de Crohn es una enfermedad de los intestinos que causa síntomas severos de dolor, diarrea y fatiga. Si bien no existe una cura para la enfermedad de Crohn, muchas personas experimentan p

Remisión de Crohn

La enfermedad de Crohn es una enfermedad de los intestinos que causa síntomas severos de dolor, diarrea y fatiga. Si bien no existe una cura para la enfermedad de Crohn, muchas personas experimentan p

Mucormicosis (zigomicosis)

Datos que debe saber sobre la mucormicosis (cigomicosis) La mucormicosis (zigomicosis) es una infección fúngica causada por Zygomycetes . Los síntomas incluyen fiebre, dolor de cabeza, tos, dificul

Mucormicosis (zigomicosis)

Datos que debe saber sobre la mucormicosis (cigomicosis) La mucormicosis (zigomicosis) es una infección fúngica causada por Zygomycetes . Los síntomas incluyen fiebre, dolor de cabeza, tos, dificul