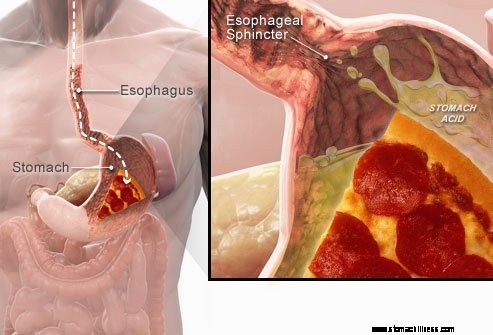

Quando ingerisci il cibo, viaggia lungo l'esofago e passa attraverso un anello muscolare noto come sfintere esofageo inferiore ( LES). Questa struttura si apre per consentire al cibo di passare nello stomaco. Dovrebbe rimanere chiuso per mantenere il contenuto dello stomaco al suo posto.

Quando ingerisci il cibo, viaggia lungo l'esofago e passa attraverso un anello muscolare noto come sfintere esofageo inferiore ( LES). Questa struttura si apre per consentire al cibo di passare nello stomaco. Dovrebbe rimanere chiuso per mantenere il contenuto dello stomaco al suo posto.

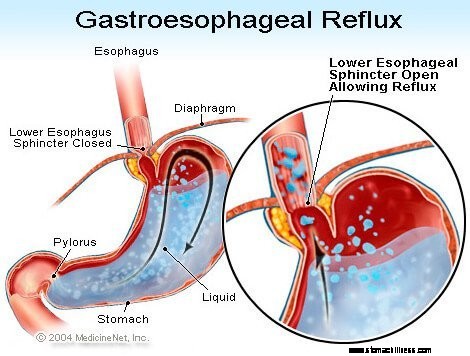

GERD o sintomi di reflusso acido sono causati dal rigurgito del contenuto liquido dello stomaco acido nell'esofago. Il sintomo più comune di GERD è il bruciore di stomaco.

Altri sintomi che possono verificarsi a seguito di GERD includono:

Il sintomo più comune di GERD è il bruciore di stomaco.

Il sintomo più comune di GERD è il bruciore di stomaco. La malattia da reflusso gastroesofageo, comunemente indicata come GERD o reflusso acido, è una condizione in cui il contenuto liquido dello stomaco rigurgita (esegue il backup o reflusso) nell'esofago. Il liquido può infiammare e danneggiare il rivestimento (esofagite), sebbene in una minoranza di pazienti si manifestino segni visibili di infiammazione. Il liquido rigurgitato di solito contiene acido e pepsina che sono prodotte dallo stomaco. (La pepsina è un enzima che avvia la digestione delle proteine nello stomaco.) Il liquido di riflusso può anche contenere la bile che è tornata nello stomaco dal duodeno. La prima parte dell'intestino tenue attaccata allo stomaco. Si ritiene che l'acido sia il componente più dannoso del liquido di riflusso. Anche la pepsina e la bile possono danneggiare l'esofago, ma il loro ruolo nella produzione dell'infiammazione e del danno esofageo non è chiaro come il ruolo dell'acido.

GERD è una condizione cronica. Una volta che inizia, di solito dura tutta la vita. Se c'è una lesione al rivestimento dell'esofago (esofagite), anche questa è una condizione cronica. Inoltre, dopo che l'esofago è guarito con il trattamento e l'interruzione del trattamento, la lesione si ripresenta nella maggior parte dei pazienti entro pochi mesi. Una volta che il trattamento per GERD è iniziato, dovrà essere continuato a tempo indeterminato. Tuttavia, alcuni pazienti con sintomi intermittenti e senza esofagite possono essere trattati solo durante periodi sintomatici.

Infatti, il reflusso del contenuto liquido dello stomaco nell'esofago si verifica nella maggior parte degli individui normali. Uno studio ha scoperto che il reflusso si verifica frequentemente negli individui normali come nei pazienti con GERD. Nei pazienti con GERD, tuttavia, il liquido di riflusso contiene acido più spesso e l'acido rimane nell'esofago più a lungo. È stato anche riscontrato che i reflui liquidi a un livello più alto nell'esofago nei pazienti con GERD rispetto agli individui normali.

Come spesso accade, il corpo ha dei modi per proteggersi dagli effetti dannosi del reflusso e dell'acido. Ad esempio, la maggior parte del reflusso si verifica durante il giorno quando gli individui sono in posizione verticale. In posizione eretta, è più probabile che il liquido di riflusso rifluisca nello stomaco a causa dell'effetto della gravità. Inoltre, mentre gli individui sono svegli, deglutiscono ripetutamente, indipendentemente dal fatto che vi sia o meno un reflusso. Ogni rondine trasporta il liquido di riflusso nello stomaco. Infine, le ghiandole salivari della bocca producono saliva, che contiene bicarbonato. Ad ogni deglutizione, la saliva contenente bicarbonato viaggia lungo l'esofago. Il bicarbonato neutralizza la piccola quantità di acido che rimane nell'esofago dopo che la gravità e la deglutizione hanno rimosso la maggior parte del liquido acido.

La gravità, la deglutizione e la saliva sono importanti meccanismi di protezione dell'esofago, ma sono efficaci solo quando gli individui sono in posizione eretta. Di notte durante il sonno, la gravità non ha effetto, la deglutizione si interrompe e la secrezione di saliva si riduce. Pertanto, è più probabile che il reflusso che si verifica di notte provochi una permanenza di acido nell'esofago più a lungo e causi maggiori danni all'esofago.

Alcune condizioni rendono una persona suscettibile a GERD. Ad esempio, GERD può essere un problema serio durante la gravidanza. I livelli elevati di ormone della gravidanza probabilmente causano reflusso abbassando la pressione nello sfintere esofageo inferiore (vedi sotto). Allo stesso tempo, il feto in crescita aumenta la pressione nell'addome. Ci si aspetta che entrambi questi effetti aumentino il reflusso. Inoltre, i pazienti con malattie che indeboliscono i muscoli esofagei, come la sclerodermia o le malattie miste del tessuto connettivo, sono più inclini a sviluppare GERD.

La causa di GERD è complessa e può coinvolgere più cause. Inoltre, cause diverse possono interessare individui diversi o anche nello stesso individuo in momenti diversi. Un piccolo numero di pazienti con GERD produce quantità anormalmente elevate di acido, ma questo è raro e non è un fattore che contribuisce nella stragrande maggioranza dei pazienti.

I fattori che contribuiscono alla GERD sono:

L'azione dello sfintere esofageo inferiore (LES) è forse il fattore (meccanismo) più importante per prevenire il reflusso. L'esofago è un tubo muscolare che si estende dalla gola inferiore allo stomaco. Il LES è un anello muscolare specializzato che circonda l'estremità più bassa dell'esofago dove si unisce allo stomaco. Il muscolo che compone il LES è attivo per la maggior parte del tempo, cioè a riposo. Ciò significa che si sta contraendo e chiudendo il passaggio dall'esofago allo stomaco. Questa chiusura del passaggio impedisce il reflusso. Quando il cibo o la saliva vengono ingeriti, il LES si rilassa per alcuni secondi per consentire al cibo o alla saliva di passare dall'esofago allo stomaco, quindi si richiude.

Diverse diverse anomalie del LES sono state trovate in pazienti con GERD. Due di loro coinvolgono la funzione del LES. Il primo è la contrazione anormalmente debole del LES, che riduce la sua capacità di prevenire il reflusso. Il secondo sono i rilassamenti anormali del LES, chiamati rilassamenti transitori del LES. Sono anormali in quanto non accompagnano le rondini e durano a lungo, fino a diversi minuti. Questi rilassamenti prolungati consentono al reflusso di verificarsi più facilmente. I rilassamenti transitori del LES si verificano nei pazienti con GERD più comunemente dopo i pasti quando lo stomaco è disteso con il cibo. Rilassamenti transitori del LES si verificano anche in individui senza GERD, ma sono rari.

L'anomalia descritta più di recente nei pazienti con GERD è la lassità del LES. In particolare, pressioni di distensione simili aprono il LES più nei pazienti con GERD che negli individui senza GERD. Almeno in teoria, ciò consentirebbe una più facile apertura del LES e/o un maggiore flusso all'indietro di acido nell'esofago quando il LES è aperto.

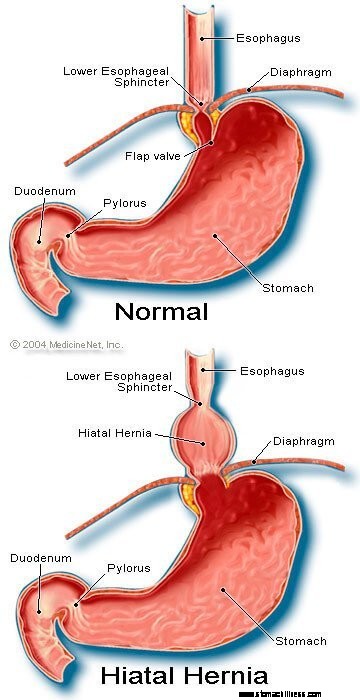

Le ernie iatali contribuiscono al reflusso, anche se il modo in cui contribuiscono non è chiaro. La maggior parte dei pazienti con GERD ha ernie iatali, ma molti no. Pertanto, non è necessario avere un'ernia iatale per avere GERD. Inoltre, molte persone hanno ernie iatali ma non hanno GERD. Non è noto con certezza come o perché si sviluppino le ernie iatali.

Normalmente, il LES si trova allo stesso livello in cui l'esofago passa dal torace attraverso una piccola apertura nel diaframma e nell'addome. (Il diaframma è una partizione orizzontale muscolare che separa il torace dall'addome.) Quando c'è un'ernia iatale, una piccola parte della parte superiore dello stomaco che si attacca all'esofago spinge verso l'alto attraverso il diaframma. Di conseguenza, una piccola parte dello stomaco e il LES arrivano a giacere nel torace e il LES non è più a livello del diaframma.

Immagine di ernia iatale

Immagine di ernia iatale

Sembra che il diaframma che circonda il LES sia importante per prevenire il reflusso. Cioè, negli individui senza ernie iatali, il diaframma che circonda l'esofago è continuamente contratto, ma poi si rilassa con le rondini, proprio come il LES. Si noti che gli effetti del LES e del diaframma si verificano nella stessa posizione nei pazienti senza ernie iatali. Pertanto, la barriera al reflusso è uguale alla somma delle pressioni generate dal LES e dal diaframma. Quando il LES si sposta nel torace con un'ernia iatale, il diaframma e il LES continuano a esercitare le loro pressioni e l'effetto barriera. Tuttavia, ora lo fanno in luoghi diversi. Di conseguenza, le pressioni non sono più additivi. Invece, un'unica barriera ad alta pressione al reflusso è sostituita da due barriere a pressione più bassa, e quindi il reflusso si verifica più facilmente. Quindi, diminuendo la barriera pressoria è un modo in cui un'ernia iatale può contribuire al reflusso.

Come accennato in precedenza, le rondini sono importanti per eliminare l'acido nell'esofago. L'ingestione provoca un'onda di contrazione ad anello dei muscoli esofagei, che restringe il lume (cavità interna) dell'esofago. La contrazione, denominata peristalsi, inizia nell'esofago superiore e viaggia nell'esofago inferiore. Spinge cibo, saliva e qualsiasi altra cosa nell'esofago nello stomaco.

Quando l'onda di contrazione è difettosa, l'acido reflusso non viene respinto nello stomaco. Nei pazienti con GERD sono state descritte diverse anomalie della contrazione. Ad esempio, le onde di contrazione potrebbero non iniziare dopo ogni deglutizione o le onde di contrazione potrebbero estinguersi prima di raggiungere lo stomaco. Inoltre, la pressione generata dalle contrazioni potrebbe essere troppo debole per respingere l'acido nello stomaco. Tali anomalie di contrazione, che riducono la clearance dell'acido dall'esofago, si riscontrano frequentemente nei pazienti con GERD. In effetti, si trovano più frequentemente in quei pazienti con la GERD più grave. Ci si aspetta che gli effetti delle contrazioni esofagee anormali siano peggiori di notte quando la gravità non aiuta a restituire l'acido reflusso allo stomaco. Si noti che il fumo riduce anche sostanzialmente la clearance dell'acido dall'esofago. Questo effetto persiste per almeno 6 ore dopo l'ultima sigaretta.

La maggior parte del reflusso durante il giorno si verifica dopo i pasti. Questo reflusso è probabilmente dovuto a rilassamenti transitori del LES causati dalla distensione dello stomaco con il cibo. È stato riscontrato che una minoranza di pazienti con GERD ha lo stomaco che si svuota in modo anomalo lentamente dopo un pasto. Questo è chiamato gastroparesi. Lo svuotamento più lento dello stomaco prolunga la distensione dello stomaco con il cibo dopo i pasti. Pertanto, lo svuotamento più lento prolunga il periodo di tempo durante il quale è più probabile che si verifichi il reflusso. Esistono diversi farmaci associati allo svuotamento gastrico alterato, come ad esempio:

Gli individui non devono interrompere l'assunzione di questi o di altri farmaci prescritti fino a quando il medico prescrittore non ha discusso con loro la potenziale situazione di GERD.

I sintomi di GERD semplice sono principalmente:

Altri sintomi si verificano quando ci sono complicazioni di GERD e saranno discussi con le complicazioni.

Quando l'acido refluisce nell'esofago nei pazienti con GERD, le fibre nervose nell'esofago vengono stimolate. Questa stimolazione nervosa provoca più comunemente il bruciore di stomaco, il dolore caratteristico della GERD. Il bruciore di stomaco è generalmente descritto come un dolore bruciante nel mezzo del torace. Può iniziare in alto nell'addome o può estendersi fino al collo. In alcuni pazienti, tuttavia, il dolore può essere acuto o simile a una pressione, piuttosto che bruciore. Tale dolore può imitare il dolore al cuore (angina). In altri pazienti, il dolore può estendersi alla schiena.

Poiché il reflusso acido è più comune dopo i pasti, il bruciore di stomaco è più comune dopo i pasti. Il bruciore di stomaco è anche più comune quando gli individui si sdraiano perché senza gli effetti della gravità, il reflusso si verifica più facilmente e l'acido viene restituito allo stomaco più lentamente. Molti pazienti con GERD vengono svegliati dal sonno dal bruciore di stomaco.

Gli episodi di bruciore di stomaco tendono a verificarsi periodicamente. Ciò significa che gli episodi sono più frequenti o gravi per un periodo di diverse settimane o mesi, per poi diventare meno frequenti o gravi o addirittura assenti per diverse settimane o mesi. Questa periodicità dei sintomi fornisce il razionale per il trattamento intermittente nei pazienti con GERD che non hanno esofagite. Tuttavia, il bruciore di stomaco è un problema che dura tutta la vita e quasi sempre si ripresenta.

Il rigurgito è la comparsa di liquido reflusso in bocca. Nella maggior parte dei pazienti con GERD, di solito solo piccole quantità di liquido raggiungono l'esofago e il liquido rimane nell'esofago inferiore. Occasionalmente in alcuni pazienti con GERD, quantità maggiori di liquidi, a volte contenenti cibo, vengono refluite e raggiungono l'esofago superiore.

All'estremità superiore dell'esofago si trova lo sfintere esofageo superiore (UES). L'UES è un anello muscolare circolare che è molto simile nelle sue azioni al LES. Cioè, l'UES impedisce al contenuto esofageo di risalire nella gola. Quando piccole quantità di liquidi e/o alimenti refluiti oltrepassano l'UES ed entrano nella gola, potrebbe esserci un sapore acido in bocca. Se quantità maggiori superano l'UES, i pazienti possono improvvisamente trovare la bocca piena di liquidi o cibo. Inoltre, un rigurgito frequente o prolungato può portare a erosioni dei denti indotte dall'acido.

La nausea è rara nella GERD. In alcuni pazienti, tuttavia, può essere frequente o grave e può provocare vomito. Infatti, nei pazienti con nausea e/o vomito inspiegabili, la GERD è una delle prime condizioni da considerare. Non è chiaro perché alcuni pazienti con GERD sviluppino principalmente bruciore di stomaco e altri sviluppino principalmente nausea.

Il liquido dallo stomaco che refluisce nell'esofago danneggia le cellule che rivestono l'esofago. Il corpo risponde nel modo in cui di solito risponde al danno, ovvero con l'infiammazione (esofagite). Lo scopo dell'infiammazione è neutralizzare l'agente dannoso e iniziare il processo di guarigione. Se il danno penetra in profondità nell'esofago, si forma un'ulcera. Un'ulcera è semplicemente un'interruzione del rivestimento dell'esofago che si verifica in un'area infiammatoria. Le ulcere e l'ulteriore infiammazione che provocano possono erodere i vasi sanguigni esofagei e dare origine a sanguinamento nell'esofago.

Occasionalmente, l'emorragia è grave e può richiedere:

Le ulcere dell'esofago guariscono con la formazione di cicatrici (fibrosi). Nel tempo, il tessuto cicatriziale si restringe e restringe il lume (cavità interna) dell'esofago. Questo restringimento sfregiato è chiamato stenosi. Il cibo ingerito può rimanere bloccato nell'esofago una volta che il restringimento diventa abbastanza grave (di solito quando limita il lume esofageo a un diametro di un centimetro). Questa situazione può richiedere la rimozione endoscopica del cibo bloccato. Quindi, per evitare che il cibo si attacchi, il restringimento deve essere allungato (allargato). Inoltre, per prevenire il ripetersi della stenosi, è necessario prevenire anche il reflusso.

GERD di lunga data e/o grave provoca cambiamenti nelle cellule che rivestono l'esofago in alcuni pazienti. Queste cellule sono precancerose e possono, sebbene di solito, diventare cancerose. Questa condizione è indicata come esofago di Barrett e si verifica in circa il 10% dei pazienti con GERD. Il tipo di cancro esofageo associato all'esofago di Barrett (adenocarcinoma) sta aumentando di frequenza. Non è chiaro il motivo per cui alcuni pazienti con GERD sviluppano l'esofago di Barrett, ma la maggior parte no.

L'esofago di Barrett può essere riconosciuto visivamente al momento di un'endoscopia e confermato dall'esame microscopico delle cellule di rivestimento. Quindi, i pazienti con esofago di Barrett possono essere sottoposti a periodiche endoscopie di sorveglianza con biopsie sebbene non vi sia accordo su quali pazienti richiedono la sorveglianza. Lo scopo della sorveglianza è rilevare la progressione dal pre-cancro a cambiamenti più cancerosi in modo da poter iniziare un trattamento di prevenzione del cancro. Si ritiene inoltre che i pazienti con esofago di Barrett debbano ricevere il massimo trattamento per GERD per prevenire ulteriori danni all'esofago. Sono allo studio procedure che rimuovono le cellule di rivestimento anormali. Diverse tecniche endoscopiche e non chirurgiche possono essere utilizzate per rimuovere le cellule. Queste tecniche sono attraenti perché non richiedono un intervento chirurgico; tuttavia, sono associate a complicazioni e l'efficacia a lungo termine dei trattamenti non è stata ancora determinata. La rimozione chirurgica dell'esofago è sempre un'opzione.

Molti nervi si trovano nell'esofago inferiore. Alcuni di questi nervi sono stimolati dal reflusso acido e questa stimolazione provoca dolore (di solito bruciore di stomaco). Altri nervi che vengono stimolati non producono dolore. Invece, stimolano ancora altri nervi che provocano la tosse. In questo modo, il liquido di riflusso può provocare la tosse senza mai raggiungere la gola! In modo simile, il reflusso nell'esofago inferiore può stimolare i nervi esofagei che si connettono e possono stimolare i nervi che vanno ai polmoni. Questi nervi ai polmoni possono quindi causare il restringimento dei tubi respiratori più piccoli, provocando un attacco di asma.

Sebbene la GERD possa causare tosse, non è una causa comune di tosse inspiegabile. Sebbene anche la GERD possa essere una causa di asma, è più probabile che precipiti attacchi asmatici in pazienti che hanno già l'asma. Sebbene la tosse cronica e l'asma siano disturbi comuni, non è chiaro con quale frequenza siano aggravati o causati da GERD.

Se il liquido di riflusso supera lo sfintere esofageo superiore, può entrare nella gola (faringe) e persino nella casella vocale (laringe). L'infiammazione risultante può portare a mal di gola e raucedine. Come per la tosse e l'asma, non è chiaro quanto comunemente la GERD sia responsabile di un'infiammazione altrimenti inspiegabile della gola e della laringe.

Il liquido di riflusso che passa dalla gola (faringe) e nella laringe può entrare nei polmoni (aspirazione). Il riflusso di liquidi nei polmoni (chiamato aspirazione) provoca spesso tosse e soffocamento. L'aspirazione, tuttavia, può verificarsi anche senza produrre questi sintomi. Con o senza questi sintomi, l'aspirazione può portare a infezioni dei polmoni e provocare polmonite. Questo tipo di polmonite è un problema serio che richiede un trattamento immediato. Quando l'aspirazione non è accompagnata da sintomi, può provocare una lenta e progressiva cicatrizzazione dei polmoni (fibrosi polmonare) che può essere vista sui raggi X del torace. È più probabile che l'aspirazione avvenga di notte perché è quando i processi (meccanismi) che proteggono dal reflusso non sono attivi e anche il riflesso della tosse che protegge i polmoni non è attivo.

La gola comunica con i passaggi nasali. Nei bambini piccoli, due chiazze di tessuto linfatico, chiamate adenoidi, si trovano dove la parte superiore della gola si unisce ai passaggi nasali. I passaggi dei seni e dei tubi dell'orecchio medio (trombe di Eustachio) si aprono nella parte posteriore dei passaggi nasali vicino alle adenoidi. Il liquido di riflusso che entra nella parte superiore della gola può infiammare le adenoidi e farle gonfiare. Le adenoidi gonfie possono quindi bloccare i passaggi dai seni e dalle trombe di Eustachio. Quando i seni e le orecchie medie sono chiusi dai passaggi nasali dal gonfiore delle adenoidi, il liquido si accumula al loro interno. Questo accumulo di liquido può causare disagio nei seni paranasali e nelle orecchie. Poiché le adenoidi sono prominenti nei bambini piccoli e non negli adulti, questo accumulo di liquido nelle orecchie e nei seni si osserva nei bambini e non negli adulti.

Esistono diverse procedure, test e valutazione dei sintomi (ad esempio, bruciore di stomaco) per diagnosticare e valutare i pazienti con GERD.

Il solito modo in cui GERD è il suo sintomo caratteristico, il bruciore di stomaco. Il bruciore di stomaco è più frequentemente descritto come un bruciore sottosternale (sotto la parte centrale del torace) che si verifica dopo i pasti e spesso peggiora quando si è sdraiati. Per confermare la diagnosi, i medici spesso trattano i pazienti con farmaci per sopprimere la produzione di acido da parte dello stomaco. Se il bruciore di stomaco è quindi ridotto in larga misura, la diagnosi di GERD è considerata confermata. Questo approccio di fare una diagnosi sulla base di una risposta dei sintomi al trattamento è comunemente chiamato prova terapeutica.

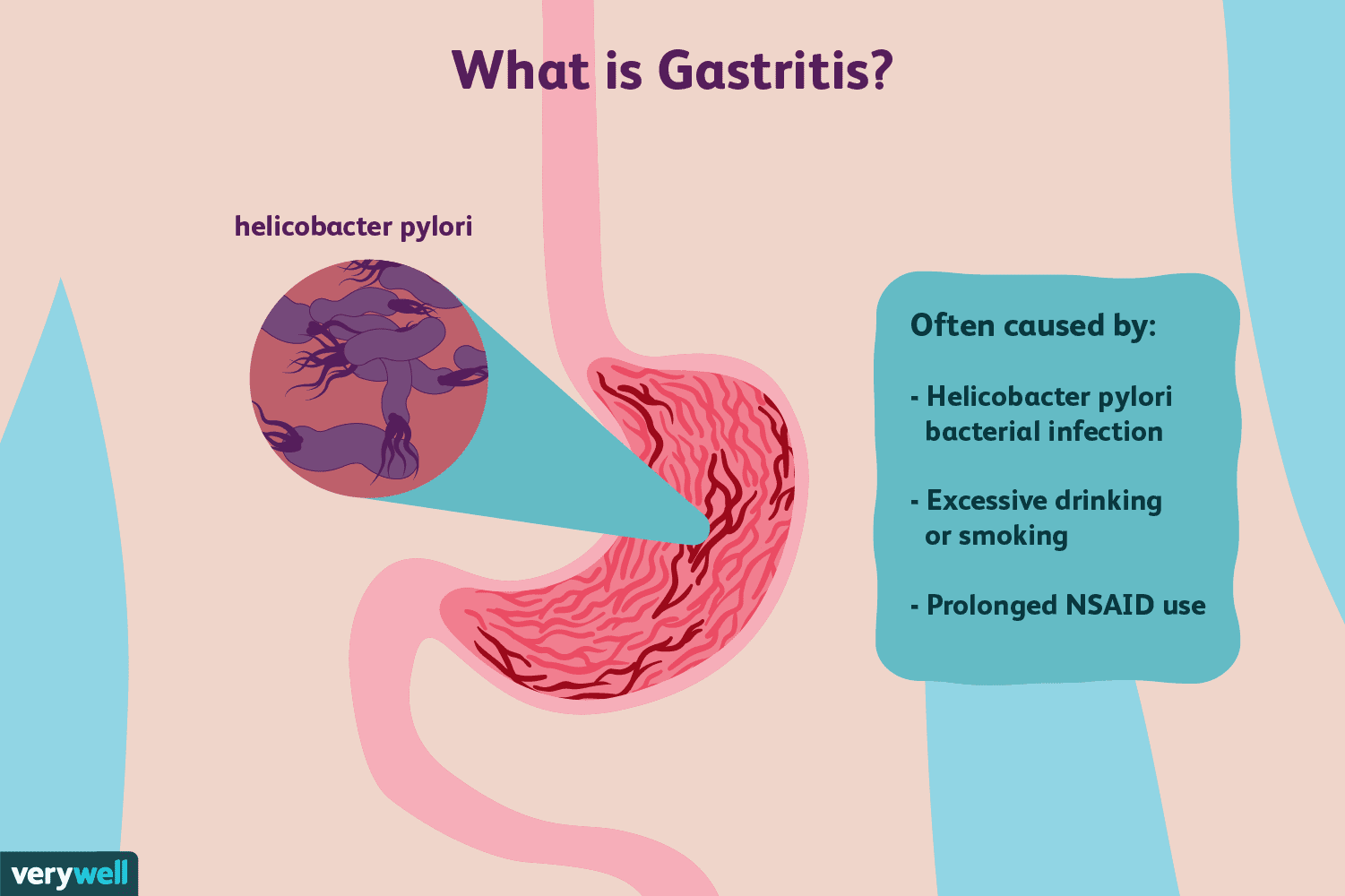

Ci sono problemi con questo approccio. Ad esempio, i pazienti che hanno condizioni che possono simulare GERD, in particolare ulcere duodenali o gastriche (stomaco), possono anche effettivamente rispondere a tale trattamento. In questa situazione, se il medico presume che il problema sia GERD, la causa della malattia dell'ulcera verrebbe ignorata come un tipo di infezione chiamata Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori ), o farmaci antinfiammatori non steroidei o FANS (ad esempio, ibuprofene), possono anche causare ulcere e queste condizioni sarebbero trattate in modo diverso dalla GERD.

Inoltre, come con qualsiasi trattamento, esiste forse un effetto placebo del 20%, il che significa che il 20% dei pazienti risponderà a una pillola placebo (inattiva) o, in effetti, a qualsiasi trattamento. Ciò significa che il 20% dei pazienti che hanno cause dei loro sintomi diverse da GERD (o ulcere) avranno una diminuzione dei loro sintomi dopo aver ricevuto il trattamento per GERD. Pertanto, sulla base della loro risposta al trattamento (lo studio terapeutico), questi pazienti continueranno a essere trattati per GERD, anche se non hanno GERD. Inoltre, la vera causa dei loro sintomi non verrà perseguita.

L'endoscopia del tratto gastrointestinale superiore (nota anche come esofago-gastro-duodenoscopia o EGD) è un modo comune per diagnosticare la GERD. L'EGD è una procedura in cui viene ingerita una provetta contenente un sistema ottico per la visualizzazione. Man mano che il tubo avanza lungo il tratto gastrointestinale, è possibile esaminare il rivestimento dell'esofago, dello stomaco e del duodeno.

L'esofago della maggior parte dei pazienti con sintomi di reflusso sembra normale. Pertanto, nella maggior parte dei pazienti, l'endoscopia non aiuta nella diagnosi di GERD. Tuttavia, a volte il rivestimento dell'esofago appare infiammato (esofagite). Inoltre, se si osservano erosioni (rotture superficiali nel rivestimento esofageo) o ulcere (rotture più profonde nel rivestimento), è possibile fare una diagnosi di GERD con sicurezza. L'endoscopia identificherà anche molte delle complicanze della GERD, in particolare ulcere, stenosi e l'esofago di Barrett. Si possono anche ottenere biopsie.

Infine, con l'EGD possono essere diagnosticati altri problemi comuni che potrebbero causare sintomi simili alla GERD (ad esempio ulcere, infiammazioni o tumori dello stomaco o del duodeno).

Le biopsie dell'esofago ottenute attraverso l'endoscopio non sono considerate molto utili per la diagnosi di GERD. Sono utili, tuttavia, nella diagnosi di tumori o cause di infiammazione esofagea diverse dal reflusso acido, in particolare le infezioni. Inoltre, le biopsie sono l'unico mezzo per diagnosticare i cambiamenti cellulari dell'esofago di Barrett. Più recentemente, è stato suggerito che anche nei pazienti con GERD i cui esofagi appaiono normali alla vista, le biopsie mostreranno un allargamento degli spazi tra le cellule di rivestimento, forse un'indicazione di danno. È troppo presto per concludere, tuttavia, che vedere l'allargamento è abbastanza specifico per essere sicuri che la GERD sia presente.

Prima dell'introduzione dell'endoscopia, una radiografia dell'esofago (chiamata esofago) era l'unico mezzo per diagnosticare la GERD. I pazienti hanno ingerito bario (materiale di contrasto) e sono state quindi eseguite radiografie dell'esofago pieno di bario. Il problema con l'esofago era che si trattava di un test insensibile per la diagnosi di GERD. Cioè, non è riuscito a trovare segni di GERD in molti pazienti che avevano GERD perché i pazienti avevano poco o nessun danno al rivestimento dell'esofago. I raggi X sono stati in grado di mostrare solo le rare complicanze della GERD, ad esempio ulcere e stenosi. I raggi X sono stati abbandonati come mezzo per diagnosticare la GERD, sebbene possano ancora essere utili insieme all'endoscopia nella valutazione delle complicanze.

Quando la GERD colpisce la gola o la laringe e provoca sintomi di tosse, raucedine o mal di gola, i pazienti spesso visitano uno specialista dell'orecchio, del naso e della gola (ORL). L'otorinolaringoiatra trova spesso segni di infiammazione della gola o della laringe. Sebbene le malattie della gola o della laringe di solito siano la causa dell'infiammazione, a volte la GERD può essere la causa. Di conseguenza, gli specialisti otorinolaringoiatri spesso provano un trattamento di soppressione dell'acido per confermare la diagnosi di GERD. Questo approccio, tuttavia, presenta gli stessi problemi discussi sopra, risultanti dall'utilizzo della risposta al trattamento per confermare la GERD.

Il test dell'acido esofageo è considerato un "gold standard" per la diagnosi di GERD. Come discusso in precedenza, il reflusso di acido è comune nella popolazione generale. Tuttavia, i pazienti con i sintomi o le complicanze della GERD hanno un reflusso di più acido rispetto agli individui senza i sintomi o le complicanze della GERD. Inoltre, individui normali e pazienti con GERD possono essere distinti moderatamente bene l'uno dall'altro per la quantità di tempo in cui l'esofago contiene acido.

La quantità di tempo in cui l'esofago contiene acido è determinata da un test chiamato test del pH esofageo di 24 ore. (il pH è un modo matematico per esprimere la quantità di acidità.) Per questo test, un tubicino (catetere) viene fatto passare attraverso il naso e posizionato nell'esofago. Sulla punta del catetere c'è un sensore che rileva l'acido. L'altra estremità del catetere esce dal naso, si avvolge all'indietro sull'orecchio e scende fino alla vita, dove è attaccata a un registratore. Ogni volta che l'acido rifluisce nell'esofago dallo stomaco, stimola il sensore e il registratore registra l'episodio di reflusso. Dopo un periodo di tempo compreso tra 20 e 24 ore, il catetere viene rimosso e viene analizzata la registrazione del reflusso dal registratore.

Ci sono problemi con l'utilizzo del test del pH per la diagnosi di GERD. Nonostante il fatto che individui normali e pazienti con GERD possano essere separati abbastanza bene sulla base di studi sul pH, la separazione non è perfetta. Pertanto, alcuni pazienti con GERD avranno quantità normali di reflusso acido e alcuni pazienti senza GERD avranno quantità anormali di reflusso acido. Richiede qualcosa di diverso dal test del pH per confermare la presenza di GERD, ad esempio sintomi tipici, risposta al trattamento o presenza di complicanze di GERD. La malattia da reflusso gastroesofageo può anche essere diagnosticata con sicurezza quando gli episodi di bruciore di stomaco sono correlati al reflusso acido, come dimostrato dal test acido.

Il test del pH ha usi nella gestione di GERD diversi dalla semplice diagnosi di GERD. Ad esempio, il test può aiutare a determinare perché i sintomi di GERD non rispondono al trattamento. Forse dal 10 al 20% dei pazienti non avrà i sintomi sostanzialmente migliorati dal trattamento per GERD. Questa mancanza di risposta al trattamento potrebbe essere causata da un trattamento inefficace. Ciò significa che il farmaco non sta sopprimendo adeguatamente la produzione di acido da parte dello stomaco e non sta riducendo il reflusso acido. In alternativa, la mancanza di risposta può essere spiegata da una diagnosi errata di GERD. In entrambe queste situazioni, il test del pH può essere molto utile. Se il test rivela un sostanziale reflusso di acido mentre il farmaco viene continuato, il trattamento è inefficace e dovrà essere modificato. Se il test rivela una buona soppressione dell'acido con un reflusso minimo di acido, è probabile che la diagnosi di GERD sia sbagliata e che siano necessarie altre cause per i sintomi.

Il test del pH può anche essere utilizzato per aiutare a valutare se il reflusso è la causa dei sintomi (di solito bruciore di stomaco). Per effettuare questa valutazione, mentre viene eseguito il test del ph nelle 24 ore, i pazienti registrano ogni volta che presentano sintomi. Quindi, durante l'analisi del test, è possibile determinare se si è verificato o meno reflusso acido al momento dei sintomi. Se il reflusso si è verificato contemporaneamente ai sintomi, è probabile che il reflusso sia la causa dei sintomi. Se non c'era reflusso al momento dei sintomi, è improbabile che il reflusso sia la causa dei sintomi.

Infine, il test del pH può essere utilizzato per valutare i pazienti prima del trattamento endoscopico o chirurgico per GERD. Come discusso in precedenza, circa il 20% dei pazienti avrà una diminuzione dei sintomi anche se non ha GERD (l'effetto placebo). Prima del trattamento endoscopico o chirurgico, è importante identificare questi pazienti perché è improbabile che traggano beneficio dai trattamenti. Lo studio del pH può essere utilizzato per identificare questi pazienti perché avranno quantità normali di reflusso acido.

A newer method for prolonged measurement (48 hours) of acid exposure in the esophagus utilizes a small, wireless capsule that is attached to the esophagus just above the LES. The capsule is passed to the lower esophagus by a tube inserted through either the mouth or the nose. After the capsule is attached to the esophagus, the tube is removed. The capsule measures the acid refluxing into the esophagus and transmits this information to a receiver that is worn at the waist. After the study, usually after 48 hours, the information from the receiver is downloaded into a computer and analyzed. The capsule falls off of the esophagus after 3-5 days and is passed in the stool. (The capsule is not reused.)

The advantage of the capsule over standard pH testing is that there is no discomfort from a catheter that passes through the throat and nose. Moreover, with the capsule, patients look normal (they don't have a catheter protruding from their noses) and are more likely to go about their daily activities, for example, go to work, without feeling self-conscious. Because the capsule records for a longer period than the catheter (48 versus 24 hours), more data on acid reflux and symptoms are obtained. Nevertheless, it is not clear whether obtaining additional information is important.

Capsule pH testing is expensive. Sometimes the capsule does not attach to the esophagus or falls off prematurely. For periods of time the receiver may not receive signals from the capsule, and some of the information about reflux of acid may be lost. Occasionally there is pain with swallowing after the capsule has been placed, and the capsule may need to be removed endoscopically. Use of the capsule is an exciting use of new technology although it has its own specific problems.

Esophageal motility testing determines how well the muscles of the esophagus are working. For motility testing, a thin tube (catheter) is passed through a nostril, down the back of the throat, and into the esophagus. On the part of the catheter that is inside the esophagus are sensors that sense pressure. A pressure is generated within the esophagus that is detected by the sensors on the catheter when the muscle of the esophagus contracts. The end of the catheter that protrudes from the nostril is attached to a recorder that records the pressure. During the test, the pressure at rest and the relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter are evaluated. The patient then swallows sips of water to evaluate the contractions of the esophagus.

Esophageal motility testing has two important uses in evaluating GERD. The first is in evaluating symptoms that do not respond to treatment for GERD since the abnormal function of the esophageal muscle sometimes causes symptoms that resemble the symptoms of GERD. Motility testing can identify some of these abnormalities and lead to a diagnosis of an esophageal motility disorder. The second use is evaluation prior to surgical or endoscopic treatment for GERD. In this situation, the purpose is to identify patients who also have motility disorders of the esophageal muscle. The reason for this is that in patients with motility disorders, some surgeons will modify the type of surgery they perform for GERD.

Gastric emptying studies are studies that determine how well food empties from the stomach. As discussed above, about 20 % of patients with GERD have slow emptying of the stomach that may be contributing to the reflux of acid. For gastric emptying studies, the patient eats a meal that is labeled with a radioactive substance. A sensor that is similar to a Geiger counter is placed over the stomach to measure how quickly the radioactive substance in the meal empties from the stomach.

Information from the emptying study can be useful for managing patients with GERD. For example, if a patient with GERD continues to have symptoms despite treatment with the usual medications, doctors might prescribe other medications that speed-up emptying of the stomach. Alternatively, in conjunction with GERD surgery, they might do a surgical procedure that promotes a more rapid emptying of the stomach. Nevertheless, it is still debated whether a finding of reduced gastric emptying should prompt changes in the surgical treatment of GERD.

Symptoms of nausea, vomiting, and regurgitation may be due either to abnormal gastric emptying or GERD. An evaluation of gastric emptying, therefore, may be useful in identifying patients whose symptoms are due to abnormal emptying of the stomach rather than to GERD.

The acid perfusion (Bernstein) test is used to determine if chest pain is caused by acid reflux. For the acid perfusion test, a thin tube is passed through one nostril, down the back of the throat, and into the middle of the esophagus. A dilute, acid solution and a physiologic salt solution (similar to the fluid that bathes the body's cells) are alternately poured (perfused) through the catheter and into the esophagus. The patient is unaware of which solution is being infused. If the perfusion with acid provokes the patient's usual pain and perfusion of the salt solution produces no pain, it is likely that the patient's pain is caused by acid reflux.

The acid perfusion test, however, is used only rarely. A better test for correlating pain and acid reflux is a 24-hour esophageal pH or pH capsule study during which patients note when they are having pain. It then can be determined from the pH recording if there was an episode of acid reflux at the time of the pain. This is the preferable way of deciding if acid reflux is causing a patient's pain. It does not work well, however, for patients who have infrequent pain, for example every two to three days, which may be missed by a one or two day pH study. In these cases, an acid perfusion test may be reasonable.

One of the simplest treatments for GERD is referred to as life-style changes, a combination of several changes in habit, particularly related to eating.

As discussed above, reflux of acid is more injurious at night than during the day. At night, when individuals are lying down, it is easier for reflux to occur. The reason that it is easier is because gravity is not opposing the reflux, as it does in the upright position during the day. In addition, the lack of an effect of gravity allows the refluxed liquid to travel further up the esophagus and remain in the esophagus longer. These problems can be overcome partially by elevating the upper body in bed. The elevation is accomplished either by putting blocks under the bed's feet at the head of the bed or, more conveniently, by sleeping with the upper body on a foam rubber wedge. These maneuvers raise the esophagus above the stomach and partially restore the effects of gravity. It is important that the upper body and not just the head be elevated. Elevating only the head does not raise the esophagus and fails to restore the effects of gravity.

Elevation of the upper body at night generally is recommended for all patients with GERD. Nevertheless, most patients with GERD have reflux only during the day and elevation at night is of little benefit for them. It is not possible to know for certain which patients will benefit from elevation at night unless acid testing clearly demonstrates night reflux. However, patients who have heartburn, regurgitation, or other symptoms of GERD at night are probably experiencing reflux at night and definitely should elevate their upper body when sleeping. Reflux also occurs less frequently when patients lie on their left rather than their right sides.

Several changes in eating habits can be beneficial in treating GERD. Reflux is worse following meals. This probably is so because the stomach is distended with food at that time and transient relaxations of the lower esophageal sphincter are more frequent. Therefore, smaller and earlier evening meals may reduce the amount of reflux for two reasons. First, the smaller meal results in lesser distention of the stomach. Second, by bedtime, a smaller and earlier meal is more likely to have emptied from the stomach than is a larger one. As a result, reflux is less likely to occur when patients with GERD lie down to sleep.

Certain foods are known to reduce the pressure in the lower esophageal sphincter and thereby promote reflux. These foods should be avoided and include:

Fatty foods (which should be decreased) and smoking (which should be stopped) also reduce the pressure in the sphincter and promote reflux.

In addition, patients with GERD may find that other foods aggravate their symptoms. Examples are spicy or acid-containing foods, like citrus juices, carbonated beverages, and tomato juice. These foods should also be avoided if they provoke symptoms.

One novel approach to the treatment of GERD is chewing gum. Chewing gum stimulates the production of more bicarbonate-containing saliva and increases the rate of swallowing. After the saliva is swallowed, it neutralizes acid in the esophagus. In effect, chewing gum exaggerates one of the normal processes that neutralize acid in the esophagus. It is not clear, however, how effective chewing gum is in treating heartburn. Nevertheless, chewing gum after meals is certainly worth a try.

There is a variety of over-the-counter (for example, antacids and foam barriers) and prescription medications (for example, proton pump inhibitors, histamine antagonists, and promotility drugs) for treating GERD.

Despite the development of potent medications for the treatment of GERD, antacids remain a mainstay of treatment. Antacids neutralize the acid in the stomach so that there is no acid to reflux. The problem with antacids is that their action is brief. They are emptied from the empty stomach quickly, in less than an hour, and the acid then re-accumulates. The best way to take antacids, therefore, is approximately one hour after meals, which is just before the symptoms of reflux begin after a meal. Since the food from meals slows the emptying from the stomach, an antacid taken after a meal stays in the stomach longer and is effective longer. For the same reason, a second dose of antacids approximately two hours after a meal takes advantage of the continuing post-meal slower emptying of the stomach and replenishes the acid-neutralizing capacity within the stomach.

Antacids may be aluminum, magnesium, or calcium-based. Calcium-based antacids (usually calcium carbonate), unlike other antacids, stimulate the release of gastrin from the stomach and duodenum. Gastrin is the hormone that is primarily responsible for the stimulation of acid secretion by the stomach. Therefore, the secretion of acid rebounds after the direct acid-neutralizing effect of the calcium carbonate is exhausted. The rebound is due to the release of gastrin, which results in an overproduction of acid. Theoretically at least, this increased acid is not good for GERD.

Acid rebound, however, is not clinically important. That is, treatment with calcium carbonate is not less effective or safe than treatment with antacids not containing calcium carbonate. Nevertheless, the phenomenon of acid rebound is theoretically harmful. In practice, therefore, calcium-containing antacids such as Tums and Rolaids are not recommended for frequent use. The occasional use of these calcium carbonate-containing antacids, however, is not believed to be harmful. The advantages of calcium carbonate-containing antacids are their low cost, the calcium they add to the diet, and their convenience as compared to liquids.

Aluminum-containing antacids tend to cause constipation, while magnesium-containing antacids tend to cause diarrhea. If diarrhea or constipation becomes a problem, it may be necessary to switch antacids, or use antacids containing both aluminum and magnesium.

Although antacids can neutralize acid, they do so for only a short period. For substantial neutralization of acid throughout the day, antacids would need to be given frequently, at least every hour.

The first medication developed for the more effective and convenient treatment of acid-related diseases, including GERD, was a histamine antagonist, specifically cimetidine (Tagamet). Histamine is an important chemical because it stimulates acid production by the stomach. Released within the wall of the stomach, histamine attaches to receptors (binders) on the stomach's acid-producing cells and stimulates the cells to produce acid. Histamine antagonists work by blocking the receptor for histamine and thereby preventing histamine from stimulating the acid-producing cells. (Histamine antagonists are referred to as H2 antagonists because the specific receptor they block is the histamine type 2 receptor.)

As histamine is particularly important for the stimulation of acid after meals, H2 antagonists are best taken 30 minutes before meals. The reason for this timing is so that the H2 antagonists will be at peak levels in the body after the meal when the stomach is actively producing acid. H2 antagonists also can be taken at bedtime to suppress the nighttime production of acid.

H2 antagonists are very good for relieving the symptoms of GERD, particularly heartburn. However, they are not very good for healing the inflammation (esophagitis) that may accompany GERD. They are used primarily for the treatment of heartburn in GERD that is not associated with inflammation or complications, such as erosions or ulcers, strictures, or Barrett's esophagus.

Three different H2 antagonists are available by prescription, including cimetidine (Tagamet), nizatidine (Axid), and famotidine (Pepcid). Two of these, cimetidine (Tagamet HB) and famotidine (Pepcid AC, Zantac 360) are available over-the-counter (OTC), without the need for a prescription. However, the OTC dosages are lower than those available by prescription.

The second type of drug developed specifically for acid-related diseases, such as GERD, was a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), specifically, omeprazole (Prilosec). A PPI blocks the secretion of acid into the stomach by the acid-secreting cells. The advantage of a PPI over an H2 antagonist is that the PPI shuts off acid production more completely and for a longer period of time. Not only is the PPI good for treating the symptom of heartburn, but it also is good for protecting the esophagus from acid so that esophageal inflammation can heal.

PPIs are used when H2 antagonists do not relieve symptoms adequately or when complications of GERD such as erosions or ulcers, strictures, or Barrett's esophagus exist. Five different PPIs are approved for the treatment of GERD, including omeprazole (Prilosec, Dexilant), lansoprazole (Prevacid), rabeprazole (Aciphex), pantoprazole (Protonix), and esomeprazole (Nexium), and dexlansoprazole (Dexilant). A sixth PPI product consists of a combination of omeprazole and sodium bicarbonate (Zegerid). PPIs (except for Zegerid) are best taken an hour before meals. The reason for this timing is that the PPIs work best when the stomach is most actively producing acid, which occurs after meals. If the PPI is taken before the meal, it is at peak levels in the body after the meal when the acid is being made.

Pro-motility drugs work by stimulating the muscles of the gastrointestinal tract, including the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and/or colon. One pro-motility drug, metoclopramide (Reglan), is approved for GERD. Pro-motility drugs increase the pressure in the lower esophageal sphincter and strengthen the contractions (peristalsis) of the esophagus. Both effects would be expected to reduce the reflux of acid. However, these effects on the sphincter and esophagus are small. Therefore, it is believed that the primary effect of metoclopramide may be to speed up emptying of the stomach, which also would be expected to reduce reflux.

Pro-motility drugs are most effective when taken 30 minutes before meals and again at bedtime. They are not very effective for treating either the symptoms or complications of GERD. Therefore, the pro-motility agents are reserved either for patients who do not respond to other treatments or are added to enhance other treatments for GERD.

Foam barriers provide a unique form of treatment for GERD. Foam barriers are tablets that are composed of an antacid and a foaming agent. As the tablet disintegrates and reaches the stomach, it turns into foam that floats on top of the liquid contents of the stomach. The foam forms a physical barrier to the reflux of liquid. At the same time, the antacid bound to the foam neutralizes acid that comes into contact with the foam. The tablets are best taken after meals (when the stomach is distended) and when lying down, both times when reflux is more likely to occur. Foam barriers are not often used as the first or only treatment for GERD. Rather, they are added to other drugs for GERD when the other drugs are not adequately effective in relieving symptoms. There is only one foam barrier, which is a combination of aluminum hydroxide gel, magnesium trisilicate, and alginate (Gaviscon).

The drugs described above usually are effective in treating the symptoms and complications of GERD. Nevertheless, sometimes they are not. For example, despite adequate suppression of acid and relief from heartburn, regurgitation, with its potential for complications in the lungs, may still occur. Moreover, the amounts and/or numbers of drugs that are required for satisfactory treatment are sometimes so great that drug treatment is unreasonable. In such situations, surgery can effectively stop reflux.

The surgical procedure that is done to prevent reflux is technically known as fundoplication and is called reflux surgery or anti-reflux surgery. During fundoplication, any hiatal hernial sac is pulled below the diaphragm and stitched there. In addition, the opening in the diaphragm through which the esophagus passes is tightened around the esophagus. Finally, the upper part of the stomach next to the opening of the esophagus into the stomach is wrapped around the lower esophagus to make an artificial lower esophageal sphincter. All of this surgery can be done through an incision in the abdomen (laparotomy) or using a technique called laparoscopy. During laparoscopy, a small viewing device and surgical instruments are passed through several small puncture sites in the abdomen. This procedure avoids the need for a major abdominal incision.

Surgery is very effective at relieving symptoms and treating the complications of GERD. Approximately 80% of patients will have good or excellent relief of their symptoms for at least 5 to 10 years. Nevertheless, many patients who have had surgery will continue to take drugs for reflux. It is not clear whether they take the drugs because they continue to have reflux and symptoms of reflux or if they take them for symptoms that are being caused by problems other than GERD. The most common complication of fundoplication is swallowed food that sticks at the artificial sphincter. Fortunately, the sticking usually is temporary. If it is not transient, endoscopic treatment to stretch (dilate) the artificial sphincter usually will relieve the problem. Only occasionally is it necessary to re-operate to revise the prior surgery.

Very recently, endoscopic techniques for the treatment of GERD have been developed and tested. One type of endoscopic treatment involves suturing (stitching) the area of the lower esophageal sphincter, which essentially tightens the sphincter.

A second type involves the application of radio-frequency waves to the lower part of the esophagus just above the sphincter. The waves cause damage to the tissue beneath the esophageal lining and a scar (fibrosis) forms. The scar shrinks and pulls on the surrounding tissue, thereby tightening the sphincter and the area above it.

A third type of endoscopic treatment involves the injection of materials into the esophageal wall in the area of the LES. The injected material is intended to increase pressure in the LES and thereby prevent reflux. In one treatment the injected material was a polymer. Unfortunately, the injection of polymer led to serious complications, and the material for injection is no longer available. Another treatment involving injection of expandable pellets also was discontinued. Limited information is available about a third type of injection which uses gelatinous polymethylmethacrylate microspheres.

Endoscopic treatment has the advantage of not requiring surgery. It can be performed without hospitalization. Experience with endoscopic techniques is limited. It is not clear how effective they are, especially long-term. Because the effectiveness and the full extent of potential complications of endoscopic techniques are not clear, it is felt generally that endoscopic treatment should only be done as part of experimental trials.

Transient LES relaxations appear to be the most common way in which acid reflux occurs. Although there is an available drug that prevents relaxations (baclofen), it has side effects that are too frequent to be generally useful. Much attention is being directed at the development of drugs that prevent these relaxations without accompanying side effects.

There are several ways to approach the evaluation and management of GERD. The approach depends primarily on the frequency and severity of symptoms, the adequacy of the response to treatment, and the presence of complications.

For infrequent heartburn, the most common symptom of GERD, life-style changes and an occasional antacid may be all that is necessary. If heartburn is frequent, daily non-prescription-strength (over-the-counter) H2 antagonists may be adequate. A foam barrier also can be used with the antacid or H2 antagonist.

If life-style changes and antacids, non-prescription H2 antagonists, and a foam barrier do not adequately relieve heartburn, it is time to see a physician for further evaluation and to consider prescription-strength drugs. The evaluation by the physician should include an assessment for possible complications of GERD based on the presence of such symptoms or findings as:

Clues to the presence of diseases that may mimic GERD, such as gastric or duodenal ulcers and esophageal motility disorders, should be sought.

If there are no symptoms or signs of complications and no suspicion of other diseases, a therapeutic trial of acid suppression with H2 antagonists often is used. If H2 antagonists are not adequately effective, a second trial, with the more potent PPIs, can be given. Sometimes, a trial of treatment begins with a PPI and skips the H2 antagonist. If treatment relieves the symptoms completely, no further evaluation may be necessary and the effective drug, the H2 antagonist or PPI, is continued. As discussed previously, however, there are potential problems with this commonly used approach, and some physicians would recommend a further evaluation for almost all patients they see.

If at the time of evaluation, there are symptoms or signs that suggest complicated GERD or a disease other than GERD or if the relief of symptoms with H2 antagonists or PPIs is not satisfactory, a further evaluation by endoscopy (EGD) definitely should be done.

There are several possible results of endoscopy and each requires a different approach to treatment. If the esophagus is normal and no other diseases are found, the goal of treatment simply is to relieve symptoms. Therefore, prescription strength H2 antagonists or PPIs are appropriate. If damage to the esophagus (esophagitis or ulceration) is found, the goal of treatment is healing the damage. In this case, PPIs are preferred over H2 antagonists because they are more effective for healing.

If complications of GERD, such as stricture or Barrett's esophagus are found, treatment with PPIs also is more appropriate. However, the adequacy of the PPI treatment probably should be evaluated with a 24-hour pH study during treatment with the PPI. (With PPIs, although the amount of acid reflux may be reduced enough to control symptoms, it may still be abnormally high. Therefore, judging the adequacy of suppression of acid reflux by only the response of symptoms to treatment is not satisfactory.) Strictures may also need to be treated by endoscopic dilatation (widening) of the esophageal narrowing. With Barrett's esophagus, periodic endoscopic examination should be done to identify pre-malignant changes in the esophagus.

If symptoms of GERD do not respond to maximum doses of PPI, there are two options for management. The first is to perform 24-hour pH testing to determine whether the PPI is ineffective or if a disease other than GERD is likely to be present. If the PPI is ineffective, a higher dose of PPI may be tried. The second option is to go ahead without 24 hour pH testing and to increase the dose of PPI. Another alternative is to add another drug to the PPI that works in a way that is different from the PPI, for example, a pro-motility drug or a foam barrier. If necessary, all three types of drugs can be used. If there is not a satisfactory response to this maximal treatment, 24 hour pH testing should be done.

Who should consider surgery or, perhaps, an endoscopic treatment trial for GERD? (As mentioned previously, the effectiveness of the recently developed endoscopic treatments remains to be determined.) Patients should consider surgery if they have regurgitation that cannot be controlled with drugs. This recommendation is particularly important if the regurgitation results in infections in the lungs or occurs at night when aspiration into the lungs is more likely. Patients also should consider surgery if they require large doses of PPI or multiple drugs to control their reflux. It is debated whether or not a desire to be free of the need to take life-long drugs to prevent symptoms of GERD is by itself a satisfactory reason for having surgery.

Some physicians - primarily surgeons - recommend that all patients with Barrett's esophagus should have surgery. This recommendation is based on the belief that surgery is more effective than endoscopic surveillance or ablation of the abnormal tissue followed by treatment with acid-suppressing drugs in preventing both the reflux and the cancerous changes in the esophagus. There are no studies, however, demonstrating the superiority of surgery over drugs or ablation for the treatment of GERD and its complications. Moreover, the effectiveness of drug treatment can be monitored with 24 hour pH testing.

One unresolved issue in GERD is the inconsistent relationships among acid reflux, heartburn, and damage to the lining of the esophagus (esophagitis and the complications).

Clearly, we have much to learn about the relationship between acid reflux and esophageal damage, and about the processes (mechanisms) responsible for heartburn. This issue is of more than passing interest. Knowledge of the mechanisms that produce heartburn and esophageal damage raises the possibility of new treatments that would target processes other than acid reflux.

One of the more interesting theories that has been proposed to answer some of these questions involves the reason for pain when acid refluxes. It often is assumed that the pain is caused by irritating acid contacting an inflamed esophageal lining. But the esophageal lining usually is not inflamed. It is possible therefore, that the acid is stimulating the pain nerves within the esophageal wall just beneath the lining. Although this may be the case, a second explanation is supported by the work of one group of scientists. These scientists find that heartburn provoked by acid in the esophagus is associated with contraction of the muscle in the lower esophagus. Perhaps it is the contraction of the muscle that somehow leads to the pain. It also is possible, however, that the contraction is an epiphenomenon, that is, refluxed acid stimulates pain nerves and causes the muscle to contract, but it is not the contraction that causes the pain. More studies will be necessary before the exact mechanism(s) that causes heartburn is clear.

There are potentially injurious agents that can be refluxed other than acid, for example, bile. Until recently it has been impossible or difficult to accurately identify non-acid reflux and, therefore, to study whether or not non-acid reflux is injurious or can cause symptoms.

A new technology allows the accurate determination of non-acid reflux. This technology uses the measurement of impedance changes within the esophagus to identify reflux of liquid, be it acid or non-acid. By combining measurement of impedance and pH it is possible to identify reflux and to tell if the reflux is acid or non-acid. It is too early to know how important non-acid reflux is in causing esophageal damage, symptoms, or complications, but there is little doubt that this new technology will be able to resolve the issues surrounding non-acid reflux.

L-Glutammina:7 cose da fare e da non fare per le persone con permeabilità intestinale e autoimmunità

L-Glutammina:7 cose da fare e da non fare per le persone con permeabilità intestinale e autoimmunità

Come il cibo ha cambiato la mia vita:superare stanchezza schiacciante, depressione e problemi digestivi

Come il cibo ha cambiato la mia vita:superare stanchezza schiacciante, depressione e problemi digestivi

Cosa puoi mangiare quando hai la gastrite?

Cosa puoi mangiare quando hai la gastrite?

Come funzionano i sequestranti degli acidi biliari

Come funzionano i sequestranti degli acidi biliari

Lo streptococco è contagioso? 12 Sintomi e segni

Lo streptococco è contagioso? 12 Sintomi e segni

Che cos'è la gastrite?

Che cos'è la gastrite?

Come fare lo yogurt 24 ore su 24 a casa con il latte di capra (passo dopo passo con le immagini)

Ho già scritto sul blog di quanto sia importante, secondo me, lo yogurt dietetico con carboidrati specifici (AKA yogurt 24 ore) per la guarigione. Puoi leggere esattamente perché penso che tutti dovre

Come fare lo yogurt 24 ore su 24 a casa con il latte di capra (passo dopo passo con le immagini)

Ho già scritto sul blog di quanto sia importante, secondo me, lo yogurt dietetico con carboidrati specifici (AKA yogurt 24 ore) per la guarigione. Puoi leggere esattamente perché penso che tutti dovre

I microbi sulla lingua potrebbero essere usati per diagnosticare il cancro al pancreas

Ricercatori della Zhenjiang University School of Medicine, La Cina ha scoperto che linterruzione della composizione microbica del rivestimento della lingua potrebbe fungere da biomarcatore per il canc

I microbi sulla lingua potrebbero essere usati per diagnosticare il cancro al pancreas

Ricercatori della Zhenjiang University School of Medicine, La Cina ha scoperto che linterruzione della composizione microbica del rivestimento della lingua potrebbe fungere da biomarcatore per il canc

La pancolite è uguale alla colite ulcerosa?

La pancolite è una forma di colite ulcerosa (CU) che infiamma lintero intestino crasso. Vivere con la pancolite spesso richiede cure mediche e cambiamenti nello stile di vita. La colite ulcerosa (UC)

La pancolite è uguale alla colite ulcerosa?

La pancolite è una forma di colite ulcerosa (CU) che infiamma lintero intestino crasso. Vivere con la pancolite spesso richiede cure mediche e cambiamenti nello stile di vita. La colite ulcerosa (UC)