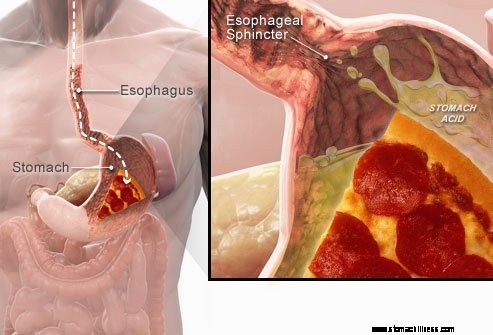

Cuando traga alimentos, estos bajan por el esófago y pasan a través de un anillo muscular conocido como esfínter esofágico inferior ( LES). Esta estructura se abre para permitir que los alimentos pasen al estómago. Se supone que debe permanecer cerrado para mantener los contenidos del estómago donde pertenecen.

Cuando traga alimentos, estos bajan por el esófago y pasan a través de un anillo muscular conocido como esfínter esofágico inferior ( LES). Esta estructura se abre para permitir que los alimentos pasen al estómago. Se supone que debe permanecer cerrado para mantener los contenidos del estómago donde pertenecen.

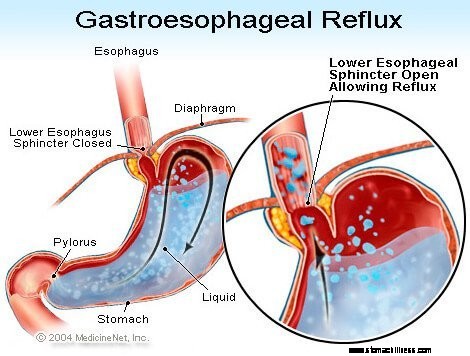

Los síntomas de ERGE o reflujo ácido son causados por la regurgitación del contenido estomacal líquido ácido hacia el esófago. El síntoma más común de la ERGE es la acidez estomacal.

Otros síntomas que pueden ocurrir como resultado de GERD incluyen:

El síntoma más común de la ERGE es la acidez estomacal.

El síntoma más común de la ERGE es la acidez estomacal. La enfermedad por reflujo gastroesofágico, comúnmente conocida como ERGE o reflujo ácido, es una afección en la que el contenido líquido del estómago regurgita (retrocede o refluye) hacia el esófago. El líquido puede inflamar y dañar el revestimiento (esofagitis), aunque se producen signos visibles de inflamación en una minoría de pacientes. El líquido regurgitado suele contener ácido y pepsina que son producidos por el estómago. (La pepsina es una enzima que inicia la digestión de proteínas en el estómago). El líquido refluido también puede contener bilis que se ha acumulado en el estómago desde el duodeno. La primera parte del intestino delgado unida al estómago. Se cree que el ácido es el componente más perjudicial del líquido a reflujo. La pepsina y la bilis también pueden dañar el esófago, pero su papel en la producción de inflamación y daño esofágico no es tan claro como el papel del ácido.

GERD es una condición crónica. Una vez que comienza, por lo general dura toda la vida. Si hay una lesión en el revestimiento del esófago (esofagitis), también es una afección crónica. Además, después de que el esófago se haya curado con el tratamiento y se detenga el tratamiento, la lesión regresará en la mayoría de los pacientes en unos pocos meses. Sin embargo, una vez que se inicia el tratamiento para la ERGE, deberá continuarse indefinidamente. Sin embargo, algunos pacientes con síntomas intermitentes y sin esofagitis pueden tratarse solo durante los períodos sintomáticos.

De hecho, el reflujo del contenido líquido del estómago hacia el esófago ocurre en la mayoría de los individuos normales. Un estudio encontró que el reflujo ocurre con frecuencia en individuos normales como en pacientes con ERGE. En pacientes con GERD, sin embargo, el líquido refluido contiene ácido con mayor frecuencia y el ácido permanece en el esófago por más tiempo. También se ha encontrado que el líquido refluye a un nivel más alto en el esófago en pacientes con ERGE que en individuos normales.

Como suele ser el caso, el cuerpo tiene formas de protegerse de los efectos nocivos del reflujo y el ácido. Por ejemplo, la mayor parte del reflujo ocurre durante el día cuando las personas están erguidas. En la posición vertical, es más probable que el líquido refluido regrese al estómago debido al efecto de la gravedad. Además, mientras los individuos están despiertos, tragan repetidamente, haya o no reflujo. Cada trago lleva cualquier líquido refluido de regreso al estómago. Finalmente, las glándulas salivales de la boca producen saliva, que contiene bicarbonato. Con cada trago, la saliva que contiene bicarbonato desciende por el esófago. El bicarbonato neutraliza la pequeña cantidad de ácido que queda en el esófago después de que la gravedad y la ingestión hayan eliminado la mayor parte del líquido ácido.

La gravedad, la deglución y la saliva son mecanismos protectores importantes para el esófago, pero solo son efectivos cuando las personas están en posición vertical. Por la noche, durante el sueño, la gravedad no tiene efecto, se detiene la deglución y se reduce la secreción de saliva. Por lo tanto, es más probable que el reflujo que ocurre por la noche provoque que el ácido permanezca en el esófago por más tiempo y cause un mayor daño al esófago.

Ciertas condiciones hacen que una persona sea susceptible a la ERGE. Por ejemplo, la ERGE puede ser un problema grave durante el embarazo. Los niveles elevados de hormonas del embarazo probablemente causen reflujo al disminuir la presión en el esfínter esofágico inferior (ver más abajo). Al mismo tiempo, el feto en crecimiento aumenta la presión en el abdomen. Se esperaría que ambos efectos aumentaran el reflujo. Además, los pacientes con enfermedades que debilitan los músculos del esófago, como la esclerodermia o enfermedades mixtas del tejido conjuntivo, son más propensos a desarrollar ERGE.

La causa de la ERGE es compleja y puede implicar múltiples causas. Además, diferentes causas pueden afectar a diferentes individuos o incluso en el mismo individuo en diferentes momentos. Un pequeño número de pacientes con ERGE produce cantidades anormalmente grandes de ácido, pero esto es poco común y no es un factor contribuyente en la gran mayoría de los pacientes.

Los factores que contribuyen a la ERGE son:

La acción del esfínter esofágico inferior (EEI) es quizás el factor (mecanismo) más importante para prevenir el reflujo. El esófago es un tubo muscular que se extiende desde la parte inferior de la garganta hasta el estómago. El LES es un anillo especializado de músculo que rodea el extremo inferior del esófago donde se une al estómago. El músculo que conforma el LES está activo la mayor parte del tiempo, es decir, en reposo. Esto significa que se está contrayendo y cerrando el paso del esófago al estómago. Este cierre del paso evita el reflujo. Cuando se traga comida o saliva, el EEI se relaja durante unos segundos para permitir que la comida o la saliva pasen del esófago al estómago y luego se vuelve a cerrar.

Se han encontrado varias anomalías diferentes del EEI en pacientes con ERGE. Dos de ellos involucran la función del LES. El primero es una contracción anormalmente débil del EEI, lo que reduce su capacidad para prevenir el reflujo. El segundo son las relajaciones anormales del LES, llamadas relajaciones transitorias del LES. Son anormales porque no acompañan a las golondrinas y duran mucho tiempo, hasta varios minutos. Estas relajaciones prolongadas permiten que el reflujo ocurra más fácilmente. Las relajaciones transitorias de LES ocurren en pacientes con GERD más comúnmente después de las comidas cuando el estómago está distendido con alimentos. Las relajaciones transitorias del EEI también ocurren en personas sin ERGE, pero son poco frecuentes.

La anomalía descrita más recientemente en pacientes con ERGE es la laxitud del EEI. Específicamente, presiones de distensión similares abren más el LES en pacientes con GERD que en individuos sin GERD. Al menos teóricamente, esto permitiría una apertura más fácil del EEI y/o un mayor reflujo de ácido hacia el esófago cuando el EEI está abierto.

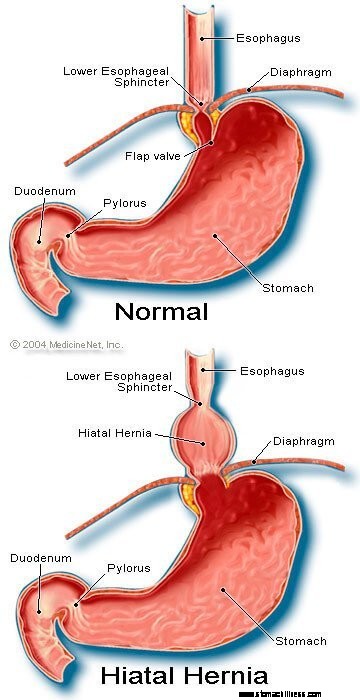

Las hernias de hiato contribuyen al reflujo, aunque no está clara la forma en que lo hacen. La mayoría de los pacientes con ERGE tienen hernias de hiato, pero muchos no. Por lo tanto, no es necesario tener una hernia de hiato para tener ERGE. Además, muchas personas tienen hernias de hiato pero no tienen ERGE. No se sabe con certeza cómo o por qué se desarrollan las hernias de hiato.

Normalmente, el LES está ubicado al mismo nivel donde el esófago pasa desde el tórax a través de una pequeña abertura en el diafragma hasta el abdomen. (El diafragma es una partición muscular horizontal que separa el tórax del abdomen). Cuando hay una hernia de hiato, una pequeña parte de la parte superior del estómago que se adhiere al esófago empuja hacia arriba a través del diafragma. Como resultado, una pequeña parte del estómago y el LES quedan en el tórax, y el LES ya no está al nivel del diafragma.

Imagen de hernia de hiato

Imagen de hernia de hiato

Parece que el diafragma que rodea el LES es importante para prevenir el reflujo. Es decir, en individuos sin hernia hiatal, el diafragma que rodea el esófago se contrae continuamente, pero luego se relaja al tragar, al igual que el LES. Tenga en cuenta que los efectos del LES y el diafragma ocurren en el mismo lugar en pacientes sin hernias de hiato. Por tanto, la barrera al reflujo es igual a la suma de las presiones generadas por el LES y el diafragma. Cuando el EEI se mueve hacia el tórax con una hernia hiatal, el diafragma y el EEI continúan ejerciendo su presión y efecto de barrera. Sin embargo, ahora lo hacen en diferentes lugares. En consecuencia, las presiones ya no son aditivas. En su lugar, una sola barrera de alta presión contra el reflujo se reemplaza por dos barreras de menor presión y, por lo tanto, el reflujo se produce más fácilmente. Por lo tanto, disminuir la barrera de presión es una forma en que una hernia de hiato puede contribuir al reflujo.

Como se mencionó anteriormente, las golondrinas son importantes para eliminar el ácido en el esófago. La deglución provoca una onda anular de contracción de los músculos del esófago, que estrecha la luz (cavidad interna) del esófago. La contracción, conocida como peristalsis, comienza en la parte superior del esófago y viaja hasta la parte inferior del esófago. Empuja la comida, la saliva y cualquier otra cosa que esté en el esófago hacia el estómago.

Cuando la onda de contracción es defectuosa, el ácido refluido no regresa al estómago. En pacientes con ERGE, se han descrito varias anomalías de la contracción. Por ejemplo, es posible que las ondas de contracción no comiencen después de cada deglución o que las ondas de contracción desaparezcan antes de llegar al estómago. Además, la presión generada por las contracciones puede ser demasiado débil para empujar el ácido hacia el estómago. Estas anomalías de la contracción, que reducen la eliminación de ácido del esófago, se encuentran con frecuencia en pacientes con ERGE. De hecho, se encuentran con mayor frecuencia en aquellos pacientes con la ERGE más grave. Se esperaría que los efectos de las contracciones esofágicas anormales fueran peores por la noche cuando la gravedad no está ayudando a devolver el ácido refluido al estómago. Tenga en cuenta que fumar también reduce sustancialmente la eliminación de ácido del esófago. Este efecto continúa durante al menos 6 horas después del último cigarrillo.

La mayor parte del reflujo durante el día ocurre después de las comidas. Este reflujo probablemente se deba a relajaciones transitorias del EEI causadas por la distensión del estómago con la comida. Se ha encontrado que una minoría de pacientes con ERGE, aproximadamente, tienen estómagos que se vacían anormalmente lentamente después de una comida. Esto se llama gastroparesia. El vaciado más lento del estómago prolonga la distensión del estómago con los alimentos después de las comidas. Por lo tanto, el vaciado más lento prolonga el período de tiempo durante el cual es más probable que ocurra el reflujo. Hay varios medicamentos asociados con el vaciamiento gástrico alterado, como:

Las personas no deben dejar de tomar estos o cualquier medicamento recetado hasta que el médico que los recetó haya discutido con ellos la posible situación de ERGE.

Los síntomas de la ERGE sin complicaciones son principalmente:

Otros síntomas ocurren cuando hay complicaciones de GERD y serán discutidos con las complicaciones.

Cuando el ácido regresa al esófago en pacientes con ERGE, se estimulan las fibras nerviosas del esófago. Esta estimulación nerviosa resulta más comúnmente en acidez estomacal, el dolor que es característico de la ERGE. La acidez estomacal generalmente se describe como un dolor ardiente en el medio del pecho. Puede comenzar en la parte alta del abdomen o puede extenderse hasta el cuello. En algunos pacientes, sin embargo, el dolor puede ser agudo o similar a una presión, en lugar de ardor. Tal dolor puede imitar el dolor del corazón (angina). En otros pacientes, el dolor puede extenderse a la espalda.

Dado que el reflujo ácido es más común después de las comidas, la acidez estomacal es más común después de las comidas. La acidez estomacal también es más común cuando las personas se acuestan porque sin los efectos de la gravedad, el reflujo ocurre más fácilmente y el ácido regresa al estómago más lentamente. Muchos pacientes con ERGE se despiertan por la acidez estomacal.

Los episodios de acidez estomacal tienden a ocurrir periódicamente. Esto significa que los episodios son más frecuentes o graves durante un período de varias semanas o meses, y luego se vuelven menos frecuentes o graves o incluso desaparecen durante varias semanas o meses. Esta periodicidad de los síntomas justifica el tratamiento intermitente en pacientes con ERGE que no tienen esofagitis. Sin embargo, la acidez estomacal es un problema de por vida y casi siempre regresa.

La regurgitación es la aparición de líquido refluido en la boca. En la mayoría de los pacientes con ERGE, por lo general, solo pequeñas cantidades de líquido llegan al esófago y el líquido permanece en la parte inferior del esófago. Ocasionalmente, en algunos pacientes con ERGE, grandes cantidades de líquido, que a veces contienen alimentos, refluyen y alcanzan la parte superior del esófago.

En el extremo superior del esófago se encuentra el esfínter esofágico superior (UES). El UES es un anillo circular de músculo que es muy similar en sus acciones al LES. Es decir, el UES evita que el contenido esofágico retroceda hacia la garganta. Cuando pequeñas cantidades de líquido y/o alimentos refluidos pasan el UES y entran en la garganta, puede haber un sabor ácido en la boca. Si grandes cantidades rompen el UES, los pacientes pueden encontrar repentinamente que sus bocas se llenan con el líquido o la comida. Además, la regurgitación frecuente o prolongada puede provocar erosiones de los dientes inducidas por el ácido.

Las náuseas son poco comunes en la ERGE. En algunos pacientes, sin embargo, puede ser frecuente o grave y provocar vómitos. De hecho, en pacientes con náuseas y/o vómitos inexplicables, la ERGE es una de las primeras condiciones a considerar. No está claro por qué algunos pacientes con ERGE desarrollan principalmente acidez estomacal y otros principalmente náuseas.

El líquido del estómago que refluye hacia el esófago daña las células que recubren el esófago. El cuerpo responde de la forma en que normalmente responde al daño, que es con inflamación (esofagitis). El propósito de la inflamación es neutralizar el agente dañino y comenzar el proceso de curación. Si el daño penetra profundamente en el esófago, se forma una úlcera. Una úlcera es simplemente una ruptura en el revestimiento del esófago que ocurre en un área de inflamación. Las úlceras y la inflamación adicional que provocan pueden erosionar los vasos sanguíneos del esófago y provocar sangrado en el esófago.

Ocasionalmente, el sangrado es severo y puede requerir:

Las úlceras del esófago se curan con la formación de cicatrices (fibrosis). Con el tiempo, el tejido cicatricial se encoge y estrecha la luz (cavidad interna) del esófago. Este estrechamiento cicatrizado se llama estenosis. Los alimentos ingeridos pueden atascarse en el esófago una vez que el estrechamiento se vuelve lo suficientemente severo (generalmente cuando restringe la luz esofágica a un diámetro de un centímetro). Esta situación puede requerir la extracción endoscópica de la comida atascada. Luego, para evitar que los alimentos se peguen, se debe estirar (ensanchar) el estrechamiento. Además, para prevenir la recurrencia de la estenosis, también se debe prevenir el reflujo.

La ERGE prolongada y/o grave provoca cambios en las células que recubren el esófago en algunos pacientes. Estas células son precancerosas y pueden, aunque normalmente, volverse cancerosas. Esta condición se conoce como esófago de Barrett y ocurre en aproximadamente el 10% de los pacientes con ERGE. El tipo de cáncer de esófago asociado con el esófago de Barrett (adenocarcinoma) está aumentando en frecuencia. No está claro por qué algunos pacientes con ERGE desarrollan esófago de Barrett, pero la mayoría no.

El esófago de Barrett puede reconocerse visualmente en el momento de una endoscopia y confirmarse mediante un examen microscópico de las células de revestimiento. Luego, los pacientes con esófago de Barrett pueden someterse a endoscopias periódicas de vigilancia con biopsias, aunque no hay acuerdo sobre qué pacientes requieren vigilancia. El propósito de la vigilancia es detectar la progresión de precáncer a cambios más cancerosos para que se pueda iniciar un tratamiento para prevenir el cáncer. También se cree que los pacientes con esófago de Barrett deben recibir el máximo tratamiento para la ERGE a fin de evitar un mayor daño al esófago. Se están estudiando procedimientos para eliminar las células de revestimiento anormales. Se pueden utilizar varias técnicas endoscópicas no quirúrgicas para extraer las células. Estas técnicas son atractivas porque no requieren cirugía; sin embargo, existen complicaciones asociadas y aún no se ha determinado la efectividad a largo plazo de los tratamientos. La extirpación quirúrgica del esófago siempre es una opción.

Muchos nervios están en el esófago inferior. Algunos de estos nervios son estimulados por el ácido refluido, y esta estimulación produce dolor (por lo general acidez estomacal). Otros nervios que se estimulan no producen dolor. En cambio, estimulan otros nervios que provocan la tos. ¡De esta manera, el líquido refluido puede causar tos sin llegar nunca a la garganta! De manera similar, el reflujo hacia la parte inferior del esófago puede estimular los nervios esofágicos que se conectan y pueden estimular los nervios que van a los pulmones. Estos nervios que van a los pulmones pueden hacer que los conductos respiratorios más pequeños se estrechen, lo que provoca un ataque de asma.

Aunque la ERGE puede causar tos, no es una causa común de tos inexplicable. Aunque la ERGE también puede ser una causa de asma, es más probable que precipite ataques de asma en pacientes que ya tienen asma. Aunque la tos crónica y el asma son dolencias comunes, no está claro con qué frecuencia se agravan o son causadas por la ERGE.

Si el líquido refluido pasa el esfínter esofágico superior, puede ingresar a la garganta (faringe) e incluso a la laringe (laringe). La inflamación resultante puede provocar dolor de garganta y ronquera. Al igual que con la tos y el asma, no está claro con qué frecuencia la ERGE es responsable de la inflamación inexplicable de la garganta y la laringe.

El líquido refluido que pasa de la garganta (faringe) a la laringe puede ingresar a los pulmones (aspiración). El reflujo de líquido a los pulmones (llamado aspiración) a menudo provoca tos y asfixia. La aspiración, sin embargo, también puede ocurrir sin producir estos síntomas. Con o sin estos síntomas, la aspiración puede provocar una infección de los pulmones y provocar neumonía. Este tipo de neumonía es un problema grave que requiere tratamiento inmediato. Cuando la aspiración no se acompaña de síntomas, puede provocar una cicatrización lenta y progresiva de los pulmones (fibrosis pulmonar) que se puede ver en las radiografías de tórax. La aspiración es más probable que ocurra durante la noche porque es cuando los procesos (mecanismos) que protegen contra el reflujo no están activos y el reflejo de la tos que protege los pulmones tampoco está activo.

La garganta se comunica con las fosas nasales. En los niños pequeños, dos parches de tejido linfático, llamados adenoides, se ubican donde la parte superior de la garganta se une a las fosas nasales. Los conductos de los senos paranasales y los conductos del oído medio (trompas de Eustaquio) desembocan en la parte posterior de los conductos nasales cerca de las adenoides. El líquido refluido que ingresa a la parte superior de la garganta puede inflamar las adenoides y hacer que se hinchen. Las adenoides inflamadas pueden bloquear los conductos de los senos paranasales y las trompas de Eustaquio. Cuando los senos paranasales y el oído medio están cerrados de las fosas nasales por la hinchazón de las adenoides, se acumula líquido dentro de ellos. Esta acumulación de líquido puede provocar molestias en los senos paranasales y los oídos. Dado que las adenoides son prominentes en los niños pequeños y no en los adultos, esta acumulación de líquido en los oídos y los senos paranasales se observa en los niños y no en los adultos.

Hay una variedad de procedimientos, pruebas y evaluación de síntomas (por ejemplo, acidez estomacal) para diagnosticar y evaluar pacientes con ERGE.

La forma habitual de que la ERGE sea por su síntoma característico, la acidez estomacal. La acidez estomacal se describe con mayor frecuencia como un ardor subesternal (debajo de la mitad del pecho) que ocurre después de las comidas y, a menudo, empeora al acostarse. Para confirmar el diagnóstico, los médicos a menudo tratan a los pacientes con medicamentos para suprimir la producción de ácido en el estómago. Si la acidez estomacal disminuye en gran medida, el diagnóstico de ERGE se considera confirmado. Este enfoque de hacer un diagnóstico sobre la base de una respuesta de los síntomas al tratamiento se denomina comúnmente ensayo terapéutico.

Hay problemas con este enfoque. Por ejemplo, los pacientes que tienen afecciones que pueden simular la ERGE, específicamente úlceras duodenales o gástricas (estómago), también pueden responder a dicho tratamiento. En esta situación, si el médico supone que el problema es la ERGE, se perdería la causa de la úlcera, como un tipo de infección llamada Helicobacter pylori. (H. pylori ), o medicamentos antiinflamatorios no esteroideos o AINE (por ejemplo, ibuprofeno), también pueden causar úlceras y estas afecciones se tratarían de manera diferente a la ERGE.

Además, como con cualquier tratamiento, quizás haya un 20% de efecto placebo, lo que significa que el 20% de los pacientes responderán a una píldora placebo (inactiva) o, de hecho, a cualquier tratamiento. Esto significa que el 20 % de los pacientes cuyas causas de los síntomas no son ERGE (o úlceras) tendrán una disminución de sus síntomas después de recibir el tratamiento para la ERGE. Por lo tanto, sobre la base de su respuesta al tratamiento (el ensayo terapéutico), estos pacientes continuarán siendo tratados por ERGE, aunque no tengan ERGE. Es más, no se perseguirá la verdadera causa de sus síntomas.

La endoscopia gastrointestinal superior (también conocida como esófago-gastro-duodenoscopia o EGD) es una forma común de diagnosticar la ERGE. La EGD es un procedimiento en el que se traga un tubo que contiene un sistema óptico para la visualización. A medida que el tubo avanza por el tracto gastrointestinal, se puede examinar el revestimiento del esófago, el estómago y el duodeno.

El esófago de la mayoría de los pacientes con síntomas de reflujo parece normal. Por lo tanto, en la mayoría de los pacientes, la endoscopia no ayudará en el diagnóstico de ERGE. Sin embargo, a veces el revestimiento del esófago aparece inflamado (esofagitis). Además, si se observan erosiones (roturas superficiales en el revestimiento del esófago) o úlceras (roturas más profundas en el revestimiento), se puede hacer un diagnóstico de ERGE con confianza. La endoscopia también identificará varias de las complicaciones de la ERGE, específicamente, úlceras, estenosis y esófago de Barrett. También se pueden obtener biopsias.

Finalmente, otros problemas comunes que pueden estar causando síntomas similares a la ERGE pueden diagnosticarse (por ejemplo, úlceras, inflamación o cánceres de estómago o duodeno) con EGD.

Las biopsias del esófago que se obtienen a través del endoscopio no se consideran muy útiles para diagnosticar la ERGE. Son útiles, sin embargo, en el diagnóstico de cánceres o causas de inflamación esofágica distintas del reflujo ácido, particularmente infecciones. Además, las biopsias son el único medio para diagnosticar los cambios celulares del esófago de Barrett. Más recientemente, se ha sugerido que incluso en pacientes con GERD cuyos esófagos parecen normales a simple vista, las biopsias mostrarán un ensanchamiento de los espacios entre las células de revestimiento, posiblemente una indicación de daño. Sin embargo, es demasiado pronto para concluir que ver un ensanchamiento es lo suficientemente específico como para estar seguro de que la ERGE está presente.

Antes de la introducción de la endoscopia, una radiografía del esófago (llamada esofagograma) era el único medio para diagnosticar la ERGE. Los pacientes ingirieron bario (material de contraste) y luego se tomaron radiografías del esófago lleno de bario. El problema con el esofagograma era que era una prueba insensible para diagnosticar la ERGE. Es decir, no pudo encontrar signos de ERGE en muchos pacientes que tenían ERGE porque los pacientes tenían poco o ningún daño en el revestimiento del esófago. Las radiografías solo pudieron mostrar las complicaciones poco frecuentes de la ERGE, por ejemplo, úlceras y estenosis. Las radiografías se han abandonado como medio para diagnosticar la ERGE, aunque todavía pueden ser útiles junto con la endoscopia en la evaluación de complicaciones.

Cuando la ERGE afecta la garganta o la laringe y causa síntomas de tos, ronquera o dolor de garganta, los pacientes suelen visitar a un especialista en oído, nariz y garganta (otorrinolaringólogo). El otorrinolaringólogo encuentra con frecuencia signos de inflamación de garganta o laringe. Aunque las enfermedades de la garganta o la laringe suelen ser la causa de la inflamación, a veces la ERGE puede ser la causa. En consecuencia, los especialistas en otorrinolaringología a menudo intentan un tratamiento supresor de ácido para confirmar el diagnóstico de ERGE. Este enfoque, sin embargo, tiene los mismos problemas que se discutieron anteriormente, que resultan del uso de la respuesta al tratamiento para confirmar la ERGE.

La prueba de ácido esofágico se considera un "estándar de oro" para diagnosticar la ERGE. Como se discutió anteriormente, el reflujo de ácido es común en la población general. Sin embargo, los pacientes con síntomas o complicaciones de GERD tienen reflujo de más ácido que los individuos sin síntomas o complicaciones de GERD. Además, los individuos normales y los pacientes con ERGE se pueden distinguir moderadamente bien entre sí por la cantidad de tiempo que el esófago contiene ácido.

La cantidad de tiempo que el esófago contiene ácido se determina mediante una prueba llamada prueba de pH esofágico de 24 horas. (El pH es una forma matemática de expresar la cantidad de acidez). Para esta prueba, se pasa un pequeño tubo (catéter) a través de la nariz y se coloca en el esófago. En la punta del catéter hay un sensor que detecta el ácido. El otro extremo del catéter sale por la nariz, se envuelve sobre la oreja y baja hasta la cintura, donde se conecta a una grabadora. Cada vez que el ácido regresa al esófago desde el estómago, estimula el sensor y la grabadora registra el episodio de reflujo. Después de un período de tiempo de 20 a 24 horas, se retira el catéter y se analiza el registro de reflujo del registrador.

Hay problemas con el uso de pruebas de pH para diagnosticar la ERGE. A pesar de que los individuos normales y los pacientes con ERGE pueden separarse bastante bien sobre la base de los estudios de pH, la separación no es perfecta. Por lo tanto, algunos pacientes con ERGE tendrán cantidades normales de reflujo ácido y algunos pacientes sin ERGE tendrán cantidades anormales de reflujo ácido. Requiere algo más que la prueba de pH para confirmar la presencia de ERGE, por ejemplo, síntomas típicos, respuesta al tratamiento o la presencia de complicaciones de ERGE. La ERGE también se puede diagnosticar con confianza cuando los episodios de acidez estomacal se correlacionan con el reflujo ácido, como lo muestran las pruebas de ácido.

La prueba de pH tiene usos en el manejo de la ERGE además de solo diagnosticar la ERGE. Por ejemplo, la prueba puede ayudar a determinar por qué los síntomas de la ERGE no responden al tratamiento. Quizás del 10 al 20 por ciento de los pacientes no mejorarán sustancialmente sus síntomas con el tratamiento de la ERGE. Esta falta de respuesta al tratamiento podría deberse a un tratamiento ineficaz. Esto significa que el medicamento no suprime adecuadamente la producción de ácido en el estómago y no reduce el reflujo ácido. Alternativamente, la falta de respuesta puede explicarse por un diagnóstico incorrecto de ERGE. En ambas situaciones, la prueba de pH puede ser muy útil. Si las pruebas revelan un reflujo sustancial de ácido mientras se continúa con la medicación, entonces el tratamiento es ineficaz y será necesario cambiarlo. Si las pruebas revelan una buena supresión del ácido con un reflujo de ácido mínimo, es probable que el diagnóstico de ERGE sea incorrecto y se deban buscar otras causas de los síntomas.

La prueba de pH también se puede usar para ayudar a evaluar si el reflujo es la causa de los síntomas (por lo general, la acidez estomacal). Para hacer esta evaluación, mientras se realiza la prueba de ph de 24 horas, los pacientes registran cada vez que tienen síntomas. Luego, cuando se analiza la prueba, se puede determinar si se produjo o no reflujo ácido en el momento de los síntomas. Si el reflujo ocurrió al mismo tiempo que los síntomas, es probable que el reflujo sea la causa de los síntomas. Si no hubo reflujo en el momento de los síntomas, es poco probable que el reflujo sea la causa de los síntomas.

Por último, la prueba de pH se puede utilizar para evaluar a los pacientes antes del tratamiento endoscópico o quirúrgico para la ERGE. Como se discutió anteriormente, alrededor del 20% de los pacientes tendrán una disminución en sus síntomas aunque no tengan ERGE (el efecto placebo). Antes del tratamiento endoscópico o quirúrgico, es importante identificar a estos pacientes porque es poco probable que se beneficien de los tratamientos. El estudio de pH se puede utilizar para identificar a estos pacientes porque tendrán cantidades normales de reflujo ácido.

A newer method for prolonged measurement (48 hours) of acid exposure in the esophagus utilizes a small, wireless capsule that is attached to the esophagus just above the LES. The capsule is passed to the lower esophagus by a tube inserted through either the mouth or the nose. After the capsule is attached to the esophagus, the tube is removed. The capsule measures the acid refluxing into the esophagus and transmits this information to a receiver that is worn at the waist. After the study, usually after 48 hours, the information from the receiver is downloaded into a computer and analyzed. The capsule falls off of the esophagus after 3-5 days and is passed in the stool. (The capsule is not reused.)

The advantage of the capsule over standard pH testing is that there is no discomfort from a catheter that passes through the throat and nose. Moreover, with the capsule, patients look normal (they don't have a catheter protruding from their noses) and are more likely to go about their daily activities, for example, go to work, without feeling self-conscious. Because the capsule records for a longer period than the catheter (48 versus 24 hours), more data on acid reflux and symptoms are obtained. Nevertheless, it is not clear whether obtaining additional information is important.

Capsule pH testing is expensive. Sometimes the capsule does not attach to the esophagus or falls off prematurely. For periods of time the receiver may not receive signals from the capsule, and some of the information about reflux of acid may be lost. Occasionally there is pain with swallowing after the capsule has been placed, and the capsule may need to be removed endoscopically. Use of the capsule is an exciting use of new technology although it has its own specific problems.

Esophageal motility testing determines how well the muscles of the esophagus are working. For motility testing, a thin tube (catheter) is passed through a nostril, down the back of the throat, and into the esophagus. On the part of the catheter that is inside the esophagus are sensors that sense pressure. A pressure is generated within the esophagus that is detected by the sensors on the catheter when the muscle of the esophagus contracts. The end of the catheter that protrudes from the nostril is attached to a recorder that records the pressure. During the test, the pressure at rest and the relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter are evaluated. The patient then swallows sips of water to evaluate the contractions of the esophagus.

Esophageal motility testing has two important uses in evaluating GERD. The first is in evaluating symptoms that do not respond to treatment for GERD since the abnormal function of the esophageal muscle sometimes causes symptoms that resemble the symptoms of GERD. Motility testing can identify some of these abnormalities and lead to a diagnosis of an esophageal motility disorder. The second use is evaluation prior to surgical or endoscopic treatment for GERD. In this situation, the purpose is to identify patients who also have motility disorders of the esophageal muscle. The reason for this is that in patients with motility disorders, some surgeons will modify the type of surgery they perform for GERD.

Gastric emptying studies are studies that determine how well food empties from the stomach. As discussed above, about 20 % of patients with GERD have slow emptying of the stomach that may be contributing to the reflux of acid. For gastric emptying studies, the patient eats a meal that is labeled with a radioactive substance. A sensor that is similar to a Geiger counter is placed over the stomach to measure how quickly the radioactive substance in the meal empties from the stomach.

Information from the emptying study can be useful for managing patients with GERD. For example, if a patient with GERD continues to have symptoms despite treatment with the usual medications, doctors might prescribe other medications that speed-up emptying of the stomach. Alternatively, in conjunction with GERD surgery, they might do a surgical procedure that promotes a more rapid emptying of the stomach. Nevertheless, it is still debated whether a finding of reduced gastric emptying should prompt changes in the surgical treatment of GERD.

Symptoms of nausea, vomiting, and regurgitation may be due either to abnormal gastric emptying or GERD. An evaluation of gastric emptying, therefore, may be useful in identifying patients whose symptoms are due to abnormal emptying of the stomach rather than to GERD.

The acid perfusion (Bernstein) test is used to determine if chest pain is caused by acid reflux. For the acid perfusion test, a thin tube is passed through one nostril, down the back of the throat, and into the middle of the esophagus. A dilute, acid solution and a physiologic salt solution (similar to the fluid that bathes the body's cells) are alternately poured (perfused) through the catheter and into the esophagus. The patient is unaware of which solution is being infused. If the perfusion with acid provokes the patient's usual pain and perfusion of the salt solution produces no pain, it is likely that the patient's pain is caused by acid reflux.

The acid perfusion test, however, is used only rarely. A better test for correlating pain and acid reflux is a 24-hour esophageal pH or pH capsule study during which patients note when they are having pain. It then can be determined from the pH recording if there was an episode of acid reflux at the time of the pain. This is the preferable way of deciding if acid reflux is causing a patient's pain. It does not work well, however, for patients who have infrequent pain, for example every two to three days, which may be missed by a one or two day pH study. In these cases, an acid perfusion test may be reasonable.

One of the simplest treatments for GERD is referred to as life-style changes, a combination of several changes in habit, particularly related to eating.

As discussed above, reflux of acid is more injurious at night than during the day. At night, when individuals are lying down, it is easier for reflux to occur. The reason that it is easier is because gravity is not opposing the reflux, as it does in the upright position during the day. In addition, the lack of an effect of gravity allows the refluxed liquid to travel further up the esophagus and remain in the esophagus longer. These problems can be overcome partially by elevating the upper body in bed. The elevation is accomplished either by putting blocks under the bed's feet at the head of the bed or, more conveniently, by sleeping with the upper body on a foam rubber wedge. These maneuvers raise the esophagus above the stomach and partially restore the effects of gravity. It is important that the upper body and not just the head be elevated. Elevating only the head does not raise the esophagus and fails to restore the effects of gravity.

Elevation of the upper body at night generally is recommended for all patients with GERD. Nevertheless, most patients with GERD have reflux only during the day and elevation at night is of little benefit for them. It is not possible to know for certain which patients will benefit from elevation at night unless acid testing clearly demonstrates night reflux. However, patients who have heartburn, regurgitation, or other symptoms of GERD at night are probably experiencing reflux at night and definitely should elevate their upper body when sleeping. Reflux also occurs less frequently when patients lie on their left rather than their right sides.

Several changes in eating habits can be beneficial in treating GERD. Reflux is worse following meals. This probably is so because the stomach is distended with food at that time and transient relaxations of the lower esophageal sphincter are more frequent. Therefore, smaller and earlier evening meals may reduce the amount of reflux for two reasons. First, the smaller meal results in lesser distention of the stomach. Second, by bedtime, a smaller and earlier meal is more likely to have emptied from the stomach than is a larger one. As a result, reflux is less likely to occur when patients with GERD lie down to sleep.

Certain foods are known to reduce the pressure in the lower esophageal sphincter and thereby promote reflux. These foods should be avoided and include:

Fatty foods (which should be decreased) and smoking (which should be stopped) also reduce the pressure in the sphincter and promote reflux.

In addition, patients with GERD may find that other foods aggravate their symptoms. Examples are spicy or acid-containing foods, like citrus juices, carbonated beverages, and tomato juice. These foods should also be avoided if they provoke symptoms.

One novel approach to the treatment of GERD is chewing gum. Chewing gum stimulates the production of more bicarbonate-containing saliva and increases the rate of swallowing. After the saliva is swallowed, it neutralizes acid in the esophagus. In effect, chewing gum exaggerates one of the normal processes that neutralize acid in the esophagus. It is not clear, however, how effective chewing gum is in treating heartburn. Nevertheless, chewing gum after meals is certainly worth a try.

There is a variety of over-the-counter (for example, antacids and foam barriers) and prescription medications (for example, proton pump inhibitors, histamine antagonists, and promotility drugs) for treating GERD.

Despite the development of potent medications for the treatment of GERD, antacids remain a mainstay of treatment. Antacids neutralize the acid in the stomach so that there is no acid to reflux. The problem with antacids is that their action is brief. They are emptied from the empty stomach quickly, in less than an hour, and the acid then re-accumulates. The best way to take antacids, therefore, is approximately one hour after meals, which is just before the symptoms of reflux begin after a meal. Since the food from meals slows the emptying from the stomach, an antacid taken after a meal stays in the stomach longer and is effective longer. For the same reason, a second dose of antacids approximately two hours after a meal takes advantage of the continuing post-meal slower emptying of the stomach and replenishes the acid-neutralizing capacity within the stomach.

Antacids may be aluminum, magnesium, or calcium-based. Calcium-based antacids (usually calcium carbonate), unlike other antacids, stimulate the release of gastrin from the stomach and duodenum. Gastrin is the hormone that is primarily responsible for the stimulation of acid secretion by the stomach. Therefore, the secretion of acid rebounds after the direct acid-neutralizing effect of the calcium carbonate is exhausted. The rebound is due to the release of gastrin, which results in an overproduction of acid. Theoretically at least, this increased acid is not good for GERD.

Acid rebound, however, is not clinically important. That is, treatment with calcium carbonate is not less effective or safe than treatment with antacids not containing calcium carbonate. Nevertheless, the phenomenon of acid rebound is theoretically harmful. In practice, therefore, calcium-containing antacids such as Tums and Rolaids are not recommended for frequent use. The occasional use of these calcium carbonate-containing antacids, however, is not believed to be harmful. The advantages of calcium carbonate-containing antacids are their low cost, the calcium they add to the diet, and their convenience as compared to liquids.

Aluminum-containing antacids tend to cause constipation, while magnesium-containing antacids tend to cause diarrhea. If diarrhea or constipation becomes a problem, it may be necessary to switch antacids, or use antacids containing both aluminum and magnesium.

Although antacids can neutralize acid, they do so for only a short period. For substantial neutralization of acid throughout the day, antacids would need to be given frequently, at least every hour.

The first medication developed for the more effective and convenient treatment of acid-related diseases, including GERD, was a histamine antagonist, specifically cimetidine (Tagamet). Histamine is an important chemical because it stimulates acid production by the stomach. Released within the wall of the stomach, histamine attaches to receptors (binders) on the stomach's acid-producing cells and stimulates the cells to produce acid. Histamine antagonists work by blocking the receptor for histamine and thereby preventing histamine from stimulating the acid-producing cells. (Histamine antagonists are referred to as H2 antagonists because the specific receptor they block is the histamine type 2 receptor.)

As histamine is particularly important for the stimulation of acid after meals, H2 antagonists are best taken 30 minutes before meals. The reason for this timing is so that the H2 antagonists will be at peak levels in the body after the meal when the stomach is actively producing acid. H2 antagonists also can be taken at bedtime to suppress the nighttime production of acid.

H2 antagonists are very good for relieving the symptoms of GERD, particularly heartburn. However, they are not very good for healing the inflammation (esophagitis) that may accompany GERD. They are used primarily for the treatment of heartburn in GERD that is not associated with inflammation or complications, such as erosions or ulcers, strictures, or Barrett's esophagus.

Three different H2 antagonists are available by prescription, including cimetidine (Tagamet), nizatidine (Axid), and famotidine (Pepcid). Two of these, cimetidine (Tagamet HB) and famotidine (Pepcid AC, Zantac 360) are available over-the-counter (OTC), without the need for a prescription. However, the OTC dosages are lower than those available by prescription.

The second type of drug developed specifically for acid-related diseases, such as GERD, was a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), specifically, omeprazole (Prilosec). A PPI blocks the secretion of acid into the stomach by the acid-secreting cells. The advantage of a PPI over an H2 antagonist is that the PPI shuts off acid production more completely and for a longer period of time. Not only is the PPI good for treating the symptom of heartburn, but it also is good for protecting the esophagus from acid so that esophageal inflammation can heal.

PPIs are used when H2 antagonists do not relieve symptoms adequately or when complications of GERD such as erosions or ulcers, strictures, or Barrett's esophagus exist. Five different PPIs are approved for the treatment of GERD, including omeprazole (Prilosec, Dexilant), lansoprazole (Prevacid), rabeprazole (Aciphex), pantoprazole (Protonix), and esomeprazole (Nexium), and dexlansoprazole (Dexilant). A sixth PPI product consists of a combination of omeprazole and sodium bicarbonate (Zegerid). PPIs (except for Zegerid) are best taken an hour before meals. The reason for this timing is that the PPIs work best when the stomach is most actively producing acid, which occurs after meals. If the PPI is taken before the meal, it is at peak levels in the body after the meal when the acid is being made.

Pro-motility drugs work by stimulating the muscles of the gastrointestinal tract, including the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and/or colon. One pro-motility drug, metoclopramide (Reglan), is approved for GERD. Pro-motility drugs increase the pressure in the lower esophageal sphincter and strengthen the contractions (peristalsis) of the esophagus. Both effects would be expected to reduce the reflux of acid. However, these effects on the sphincter and esophagus are small. Therefore, it is believed that the primary effect of metoclopramide may be to speed up emptying of the stomach, which also would be expected to reduce reflux.

Pro-motility drugs are most effective when taken 30 minutes before meals and again at bedtime. They are not very effective for treating either the symptoms or complications of GERD. Therefore, the pro-motility agents are reserved either for patients who do not respond to other treatments or are added to enhance other treatments for GERD.

Foam barriers provide a unique form of treatment for GERD. Foam barriers are tablets that are composed of an antacid and a foaming agent. As the tablet disintegrates and reaches the stomach, it turns into foam that floats on top of the liquid contents of the stomach. The foam forms a physical barrier to the reflux of liquid. At the same time, the antacid bound to the foam neutralizes acid that comes into contact with the foam. The tablets are best taken after meals (when the stomach is distended) and when lying down, both times when reflux is more likely to occur. Foam barriers are not often used as the first or only treatment for GERD. Rather, they are added to other drugs for GERD when the other drugs are not adequately effective in relieving symptoms. There is only one foam barrier, which is a combination of aluminum hydroxide gel, magnesium trisilicate, and alginate (Gaviscon).

The drugs described above usually are effective in treating the symptoms and complications of GERD. Nevertheless, sometimes they are not. For example, despite adequate suppression of acid and relief from heartburn, regurgitation, with its potential for complications in the lungs, may still occur. Moreover, the amounts and/or numbers of drugs that are required for satisfactory treatment are sometimes so great that drug treatment is unreasonable. In such situations, surgery can effectively stop reflux.

The surgical procedure that is done to prevent reflux is technically known as fundoplication and is called reflux surgery or anti-reflux surgery. During fundoplication, any hiatal hernial sac is pulled below the diaphragm and stitched there. In addition, the opening in the diaphragm through which the esophagus passes is tightened around the esophagus. Finally, the upper part of the stomach next to the opening of the esophagus into the stomach is wrapped around the lower esophagus to make an artificial lower esophageal sphincter. All of this surgery can be done through an incision in the abdomen (laparotomy) or using a technique called laparoscopy. During laparoscopy, a small viewing device and surgical instruments are passed through several small puncture sites in the abdomen. This procedure avoids the need for a major abdominal incision.

Surgery is very effective at relieving symptoms and treating the complications of GERD. Approximately 80% of patients will have good or excellent relief of their symptoms for at least 5 to 10 years. Nevertheless, many patients who have had surgery will continue to take drugs for reflux. It is not clear whether they take the drugs because they continue to have reflux and symptoms of reflux or if they take them for symptoms that are being caused by problems other than GERD. The most common complication of fundoplication is swallowed food that sticks at the artificial sphincter. Fortunately, the sticking usually is temporary. If it is not transient, endoscopic treatment to stretch (dilate) the artificial sphincter usually will relieve the problem. Only occasionally is it necessary to re-operate to revise the prior surgery.

Very recently, endoscopic techniques for the treatment of GERD have been developed and tested. One type of endoscopic treatment involves suturing (stitching) the area of the lower esophageal sphincter, which essentially tightens the sphincter.

A second type involves the application of radio-frequency waves to the lower part of the esophagus just above the sphincter. The waves cause damage to the tissue beneath the esophageal lining and a scar (fibrosis) forms. The scar shrinks and pulls on the surrounding tissue, thereby tightening the sphincter and the area above it.

A third type of endoscopic treatment involves the injection of materials into the esophageal wall in the area of the LES. The injected material is intended to increase pressure in the LES and thereby prevent reflux. In one treatment the injected material was a polymer. Unfortunately, the injection of polymer led to serious complications, and the material for injection is no longer available. Another treatment involving injection of expandable pellets also was discontinued. Limited information is available about a third type of injection which uses gelatinous polymethylmethacrylate microspheres.

Endoscopic treatment has the advantage of not requiring surgery. It can be performed without hospitalization. Experience with endoscopic techniques is limited. It is not clear how effective they are, especially long-term. Because the effectiveness and the full extent of potential complications of endoscopic techniques are not clear, it is felt generally that endoscopic treatment should only be done as part of experimental trials.

Transient LES relaxations appear to be the most common way in which acid reflux occurs. Although there is an available drug that prevents relaxations (baclofen), it has side effects that are too frequent to be generally useful. Much attention is being directed at the development of drugs that prevent these relaxations without accompanying side effects.

There are several ways to approach the evaluation and management of GERD. The approach depends primarily on the frequency and severity of symptoms, the adequacy of the response to treatment, and the presence of complications.

For infrequent heartburn, the most common symptom of GERD, life-style changes and an occasional antacid may be all that is necessary. If heartburn is frequent, daily non-prescription-strength (over-the-counter) H2 antagonists may be adequate. A foam barrier also can be used with the antacid or H2 antagonist.

If life-style changes and antacids, non-prescription H2 antagonists, and a foam barrier do not adequately relieve heartburn, it is time to see a physician for further evaluation and to consider prescription-strength drugs. The evaluation by the physician should include an assessment for possible complications of GERD based on the presence of such symptoms or findings as:

Clues to the presence of diseases that may mimic GERD, such as gastric or duodenal ulcers and esophageal motility disorders, should be sought.

If there are no symptoms or signs of complications and no suspicion of other diseases, a therapeutic trial of acid suppression with H2 antagonists often is used. If H2 antagonists are not adequately effective, a second trial, with the more potent PPIs, can be given. Sometimes, a trial of treatment begins with a PPI and skips the H2 antagonist. If treatment relieves the symptoms completely, no further evaluation may be necessary and the effective drug, the H2 antagonist or PPI, is continued. As discussed previously, however, there are potential problems with this commonly used approach, and some physicians would recommend a further evaluation for almost all patients they see.

If at the time of evaluation, there are symptoms or signs that suggest complicated GERD or a disease other than GERD or if the relief of symptoms with H2 antagonists or PPIs is not satisfactory, a further evaluation by endoscopy (EGD) definitely should be done.

There are several possible results of endoscopy and each requires a different approach to treatment. If the esophagus is normal and no other diseases are found, the goal of treatment simply is to relieve symptoms. Therefore, prescription strength H2 antagonists or PPIs are appropriate. If damage to the esophagus (esophagitis or ulceration) is found, the goal of treatment is healing the damage. In this case, PPIs are preferred over H2 antagonists because they are more effective for healing.

If complications of GERD, such as stricture or Barrett's esophagus are found, treatment with PPIs also is more appropriate. However, the adequacy of the PPI treatment probably should be evaluated with a 24-hour pH study during treatment with the PPI. (With PPIs, although the amount of acid reflux may be reduced enough to control symptoms, it may still be abnormally high. Therefore, judging the adequacy of suppression of acid reflux by only the response of symptoms to treatment is not satisfactory.) Strictures may also need to be treated by endoscopic dilatation (widening) of the esophageal narrowing. With Barrett's esophagus, periodic endoscopic examination should be done to identify pre-malignant changes in the esophagus.

If symptoms of GERD do not respond to maximum doses of PPI, there are two options for management. The first is to perform 24-hour pH testing to determine whether the PPI is ineffective or if a disease other than GERD is likely to be present. If the PPI is ineffective, a higher dose of PPI may be tried. The second option is to go ahead without 24 hour pH testing and to increase the dose of PPI. Another alternative is to add another drug to the PPI that works in a way that is different from the PPI, for example, a pro-motility drug or a foam barrier. If necessary, all three types of drugs can be used. If there is not a satisfactory response to this maximal treatment, 24 hour pH testing should be done.

Who should consider surgery or, perhaps, an endoscopic treatment trial for GERD? (As mentioned previously, the effectiveness of the recently developed endoscopic treatments remains to be determined.) Patients should consider surgery if they have regurgitation that cannot be controlled with drugs. This recommendation is particularly important if the regurgitation results in infections in the lungs or occurs at night when aspiration into the lungs is more likely. Patients also should consider surgery if they require large doses of PPI or multiple drugs to control their reflux. It is debated whether or not a desire to be free of the need to take life-long drugs to prevent symptoms of GERD is by itself a satisfactory reason for having surgery.

Some physicians - primarily surgeons - recommend that all patients with Barrett's esophagus should have surgery. This recommendation is based on the belief that surgery is more effective than endoscopic surveillance or ablation of the abnormal tissue followed by treatment with acid-suppressing drugs in preventing both the reflux and the cancerous changes in the esophagus. There are no studies, however, demonstrating the superiority of surgery over drugs or ablation for the treatment of GERD and its complications. Moreover, the effectiveness of drug treatment can be monitored with 24 hour pH testing.

One unresolved issue in GERD is the inconsistent relationships among acid reflux, heartburn, and damage to the lining of the esophagus (esophagitis and the complications).

Clearly, we have much to learn about the relationship between acid reflux and esophageal damage, and about the processes (mechanisms) responsible for heartburn. This issue is of more than passing interest. Knowledge of the mechanisms that produce heartburn and esophageal damage raises the possibility of new treatments that would target processes other than acid reflux.

One of the more interesting theories that has been proposed to answer some of these questions involves the reason for pain when acid refluxes. It often is assumed that the pain is caused by irritating acid contacting an inflamed esophageal lining. But the esophageal lining usually is not inflamed. It is possible therefore, that the acid is stimulating the pain nerves within the esophageal wall just beneath the lining. Although this may be the case, a second explanation is supported by the work of one group of scientists. These scientists find that heartburn provoked by acid in the esophagus is associated with contraction of the muscle in the lower esophagus. Perhaps it is the contraction of the muscle that somehow leads to the pain. It also is possible, however, that the contraction is an epiphenomenon, that is, refluxed acid stimulates pain nerves and causes the muscle to contract, but it is not the contraction that causes the pain. More studies will be necessary before the exact mechanism(s) that causes heartburn is clear.

There are potentially injurious agents that can be refluxed other than acid, for example, bile. Until recently it has been impossible or difficult to accurately identify non-acid reflux and, therefore, to study whether or not non-acid reflux is injurious or can cause symptoms.

A new technology allows the accurate determination of non-acid reflux. This technology uses the measurement of impedance changes within the esophagus to identify reflux of liquid, be it acid or non-acid. By combining measurement of impedance and pH it is possible to identify reflux and to tell if the reflux is acid or non-acid. It is too early to know how important non-acid reflux is in causing esophageal damage, symptoms, or complications, but there is little doubt that this new technology will be able to resolve the issues surrounding non-acid reflux.

Personas que contraen infecciones de caca de cachorros en tiendas de mascotas:CDC

Últimas noticias sobre enfermedades infecciosas En la antigüedad, incluso los ricos tenían parásitos Los CDC advierten sobre un aumento de la rabia relacionado con los murciélagos E. Brote de coli en

Personas que contraen infecciones de caca de cachorros en tiendas de mascotas:CDC

Últimas noticias sobre enfermedades infecciosas En la antigüedad, incluso los ricos tenían parásitos Los CDC advierten sobre un aumento de la rabia relacionado con los murciélagos E. Brote de coli en

Anamnesis de invaginaciones intestinales - Diagnóstico de abdomen agudo

Las estadísticas de todos los autores, excepto las estadísticas de VA Krasin, incluyen más de 100 casos. Leyhtenstern también las enfermedades agudas, directamente predshestvovavsh con intestinal a l

Anamnesis de invaginaciones intestinales - Diagnóstico de abdomen agudo

Las estadísticas de todos los autores, excepto las estadísticas de VA Krasin, incluyen más de 100 casos. Leyhtenstern también las enfermedades agudas, directamente predshestvovavsh con intestinal a l

Cómo ayudan los probióticos a mantener el intestino sano

Con todos los productos antibacterianos que hay en el mercado hoy en día, uno podría llegar fácilmente a la conclusión de que todas las bacterias son dañinas. La verdad es que el cuerpo humano contien

Cómo ayudan los probióticos a mantener el intestino sano

Con todos los productos antibacterianos que hay en el mercado hoy en día, uno podría llegar fácilmente a la conclusión de que todas las bacterias son dañinas. La verdad es que el cuerpo humano contien