Cos'è l'HCV, come si trasmette, ci sono sintomi ed è curabile?

Cos'è l'HCV, come si trasmette, ci sono sintomi ed è curabile?La maggior parte delle persone che contraggono l'epatite C (epatite C) non hanno sintomi. Tuttavia, quelli che hanno sintomi potrebbero manifestare:

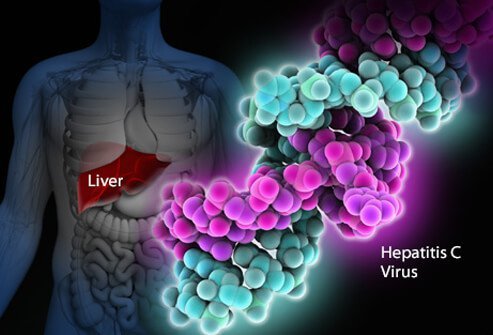

L'infezione da virus dell'epatite C è un'infezione del fegato causata dal virus dell'epatite C (indicato anche come HCV o epatite C). È difficile per il sistema immunitario umano eliminare l'epatite C dal corpo e l'infezione da epatite C di solito diventa cronica. Nel corso dei decenni, l'infezione cronica da epatite C danneggia il fegato e può causare insufficienza epatica. Negli Stati Uniti, il CDC ha stimato che nel 2016 si sono verificati circa 41.200 nuovi casi di epatite C. Quando il virus entra per la prima volta nel corpo di solito non ci sono sintomi, quindi questo numero è una stima. Circa il 75%-85% delle persone appena infette viene infettato cronicamente. Negli Stati Uniti, si stima che più di 2 milioni di persone siano infettate cronicamente dall'epatite C. L'infezione è più comunemente rilevata tra le persone di età compresa tra 40 e 60 anni, riflettendo gli alti tassi di infezione negli anni '70 e '80. Ci sono da 8.000 a 10.000 decessi ogni anno negli Stati Uniti legati all'infezione da epatite C. L'infezione da HCV è la principale causa di trapianto di fegato negli Stati Uniti ed è un fattore di rischio per il cancro al fegato. Nel 2016, 18.153 certificati di morte hanno indicato l'HCV come concausa di morte; si ritiene che questa sia una sottostima.

Circa il 10%-20% di coloro che sviluppano l'HCV cronico svilupperà la cirrosi entro 20-30 anni. La progressione alla cirrosi può essere accelerata dall'età superiore ai 50 anni, dal sesso maschile, dal consumo di alcol, dalla steatosi epatica non alcolica (NASH), dalla coinfezione con epatite B o HIV e dai farmaci immunosoppressori. L'infezione da HCV è la principale causa di trapianto di fegato a causa di insufficienza epatica negli Stati Uniti

Coloro che hanno la cirrosi da HCV hanno anche un rischio annuo di cancro al fegato (epatoma o carcinoma epatocellulare) di circa l'1%-5%.

Epatite significa infiammazione del fegato. L'epatite C è uno dei numerosi virus che possono causare l'epatite virale. Non è correlato agli altri comuni virus dell'epatite (ad esempio, l'epatite A o l'epatite B). L'epatite C è un membro dei Flaviviridae famiglia di virus. Altri membri di questa famiglia di virus includono quelli che causano la febbre gialla e la febbre dengue.

Esistono almeno sei diversi genotipi (ceppi) del virus che hanno diversi profili genetici (genotipi da 1 a 6). Negli Stati Uniti, il genotipo 1 è il ceppo più comune di epatite C. Anche all'interno di un singolo genotipo possono esserci alcune variazioni (genotipo 1a e 1b, per esempio). La genotipizzazione viene utilizzata per guidare il trattamento perché alcuni genotipi virali rispondono meglio ad alcune terapie che ad altre.

Come il virus dell'immunodeficienza umana (HIV), l'epatite C si moltiplica molto velocemente e raggiunge livelli molto elevati nel corpo. Anche i geni che fanno mutare (cambiare) rapidamente le proteine di superficie del virus e ogni giorno vengono prodotte migliaia di variazioni genetiche del virus ("quasi specie"). È impossibile per il corpo tenere il passo con la produzione di anticorpi anti-HCV contro tutte le quasi specie che circolano contemporaneamente. Non è stato ancora possibile sviluppare un vaccino efficace perché il vaccino deve proteggere da tutti i genotipi.

L'infezione da epatite C nel fegato innesca il sistema immunitario, che porta all'infiammazione. Circa il 20%-30% delle persone infette in modo acuto sperimenterà i tipici sintomi dell'epatite come dolore addominale, ittero, urine scure o feci color argilla. Tuttavia, l'epatite C cronica di solito non provoca sintomi fino a molto tardi nella malattia e l'epatite C è stata definita dai malati il "drago dormiente". Nel corso di diversi anni o decenni, l'infiammazione cronica può causare la morte delle cellule del fegato e la formazione di cicatrici ("fibrosi"). Cicatrici estese nel fegato sono chiamate cirrosi. Ciò compromette progressivamente le funzioni vitali del fegato. I fegati cirrotici sono più inclini al cancro del fegato. Bere alcol accelera il danno epatico con l'epatite C. L'infezione concomitante da HIV, così come l'infezione acuta da epatite A o B, accelererà anche la progressione verso la cirrosi.

Circa il 70%-80% delle persone non presenta sintomi quando contrae per la prima volta l'infezione da HCV. Il restante 20%-30% potrebbe averlo

I primi sintomi dell'epatite C possono includere urine scure, occhi gialli o feci color argilla, sebbene ciò sia insolito. Nel tempo, le persone con infezione cronica da HCV possono sviluppare segni di infiammazione del fegato che suggeriscono che l'infezione potrebbe essere presente. Gli individui infetti possono affaticarsi facilmente o lamentarsi di sintomi non specifici. I successivi sintomi e segni di cirrosi sono spesso assenti fino a quando l'infiammazione non è abbastanza avanzata. Con il progredire della cirrosi, i sintomi e i segni aumentano e possono includere:

Poiché l'epatite C viene trasmessa dall'esposizione al sangue, non esiste un periodo specifico di contagiosità. Le persone che sviluppano l'epatite C cronica portano il virus nel sangue e, quindi, sono contagiose per gli altri per tutta la loro vita, a meno che non siano guarite dalla loro epatite C.

È difficile dire con certezza quale sia il periodo di incubazione per l'epatite C, perché la maggior parte delle persone infette da epatite C non presenta sintomi all'inizio del corso dell'infezione. Coloro che sviluppano i sintomi subito dopo essere stati infettati (da 2 a 12 settimane in media, ma possono essere più lunghi) manifestano sintomi gastrointestinali lievi che potrebbero non richiedere una visita dal medico.

La maggior parte dei segni e dei sintomi dell'infezione da epatite C riguarda il fegato. Meno spesso, l'infezione da epatite C può colpire organi diversi dal fegato.

L'infezione da epatite C può indurre il corpo a produrre anticorpi anormali chiamati crioglobuline. Le crioglobuline causano infiammazione delle arterie (vasculite). Ciò può danneggiare la pelle, le articolazioni e i reni. I pazienti con crioglobulinemia (crioglobuline nel sangue) possono avere

Inoltre, gli individui infetti con crioglobulinemia possono sviluppare il fenomeno di Raynaud in cui le dita delle mani e dei piedi diventano colorate (bianche, poi viola, poi rosse) e diventano dolenti a basse temperature.

La task force dei servizi sanitari preventivi degli Stati Uniti raccomanda che tutti gli adulti nati tra il 1945 e il 1965 siano sottoposti a un test di routine per l'epatite C, indipendentemente dalla presenza di fattori di rischio per l'epatite C. Si consiglia inoltre di eseguire un test una tantum per:

Le persone che potrebbero essere state esposte all'epatite C nei 6 mesi precedenti dovrebbero essere testate per la carica di RNA virale piuttosto che per gli anticorpi anti-HCV, perché gli anticorpi potrebbero non essere presenti fino a 12 settimane o più dopo l'infezione, sebbene l'RNA dell'HCV possa essere rilevabile nel sangue non appena 2-3 settimane dopo l'infezione.

In generale, lo screening annuale può essere appropriato per le persone con fattori di rischio in corso come malattie sessualmente trasmissibili (MST) ripetute o molti partner sessuali, uso di droghe per via endovenosa in corso o partner sessuali a lungo termine di persone con epatite C. Se testare o meno queste persone sono determinate da una decisione caso per caso.

C'è un rischio del 4%-7% di trasmettere l'HCV dalla madre al bambino ad ogni gravidanza. Attualmente, non esiste una raccomandazione del CDC per lo screening di routine dell'epatite C durante la gravidanza e non esiste attualmente alcun medicinale raccomandato per prevenire la trasmissione dalla madre al bambino (profilassi). Tuttavia, il CDC sta monitorando i risultati della ricerca e potrebbe formulare raccomandazioni in futuro man mano che emergono prove.

Sebbene i dati siano ancora limitati, un recente studio su oltre 1.000 casi nel Regno Unito ha rilevato che l'11% dei bambini era stato infettato alla nascita e che questi bambini potevano sviluppare la cirrosi all'inizio dei 30 anni. Il caso dello screening per l'HCV durante la gravidanza include la possibilità di trattare in sicurezza le madri durante la gravidanza con agenti antivirali ad azione diretta (DAA) per trattare la madre prima che si sviluppi la cirrosi, prevenire la trasmissione infantile e prevenire la trasmissione ad altri. I bambini nati da madri con infezione da HCV possono anche ricevere cure in tenera età per prevenire la cirrosi e la trasmissione ad altri. Il coordinamento dell'assistenza tra più specialisti sarà importante per raggiungere questi obiettivi.

I bambini di madri con infezione da HCV possono essere sottoposti a screening per l'epatite C già a 1-2 mesi di età utilizzando la carica virale dell'epatite C o il test PCR (vedere Esami del sangue per l'epatite C). Gli anticorpi contro l'epatite C trasmessi dalla madre al figlio saranno presenti per un massimo di 18 mesi, quindi i bambini dovrebbero essere testati per gli anticorpi HCV non prima di questo.

L'epatite C viene trattata da un gastroenterologo, un epatologo (un gastroenterologo con formazione aggiuntiva in malattie del fegato) o uno specialista in malattie infettive. L'équipe di trattamento può comprendere più di uno specialista, a seconda dell'entità del danno epatico. I chirurghi specializzati in chirurgia del fegato, compreso il trapianto di fegato, fanno parte dell'équipe medica e dovrebbero vedere pazienti con malattia avanzata (insufficienza epatica o cirrosi) precoce, prima che il paziente necessiti di un trapianto di fegato. Possono essere in grado di identificare i problemi che devono essere affrontati prima di poter prendere in considerazione un intervento chirurgico. Altre persone che possono essere utili nella gestione dei pazienti includono dietisti da consultare su questioni nutrizionali e farmacisti per assistere nella gestione dei farmaci.

Esistono diversi esami del sangue per la diagnosi di infezione da epatite C. Il sangue può essere testato per l'anticorpo contro l'epatite C (anticorpo anti-HCV). Occorrono in media circa 8-12 settimane e fino a 6 mesi perché gli anticorpi si sviluppino dopo l'infezione iniziale con l'epatite C, quindi lo screening per gli anticorpi potrebbe non rilevare alcuni individui di nuova infezione. Avere anticorpi non è un'indicazione assoluta di virus dell'epatite C attivo che si moltiplica, ma se il test anticorpale è positivo (è presente l'anticorpo), la probabilità statistica di infezione attiva è maggiore del 99%.

Sono disponibili diversi test per misurare la quantità di virus dell'epatite C nel sangue di una persona (la carica virale). L'RNA del virus dell'epatite C può essere identificato da un tipo di test chiamato reazione a catena della polimerasi (PCR) che rileva il virus circolante nel sangue già 2-3 settimane dopo l'infezione, quindi può essere utilizzato per rilevare la sospetta infezione acuta con l'epatite C infezione precoce. Viene anche utilizzato per determinare se l'epatite attiva è presente in qualcuno che ha anticorpi contro l'epatite C e per seguire la carica virale durante il trattamento.

Vengono anche eseguiti esami del sangue per identificare i genotipi di HCV. I genotipi rispondono in modo diverso a trattamenti diversi, quindi queste informazioni sono importanti nella selezione del regime di trattamento più appropriato.

Anche la stima della fibrosi epatica mediante esami del sangue è abbastanza affidabile nella diagnosi di cicatrici clinicamente significative; questi includono FIB-4, FibroSure, Fibrotest e l'indice del rapporto aspartato aminotransferasi-piastrine (APRI).

Il passo successivo è determinare il livello di cicatrici epatiche che si sono verificate. La biopsia epatica consente l'esame di un piccolo campione di tessuto epatico al microscopio, tuttavia, la biopsia epatica è un test invasivo e presenta rischi significativi di sanguinamento. Potrebbe anche mancare aree anormali nelle prime fasi della malattia.

I test non invasivi hanno ampiamente sostituito la biopsia epatica tranne che in situazioni speciali. La rigidità epatica indica che possono essere presenti cicatrici o cirrosi epatiche avanzate. Transient elastography may be used to measure this stiffness by ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Pre-treatment evaluation for hepatitis C also should include:

Interferons, for example, Roferon-A and Infergen, and pegylated interferons such as Peg-Intron T , Pegasys, were mainstays of treatment for years. Interferons produced sustained viral response (SVR, or cure) of up to 15%. Later, peglatedll forms produced SVR of 50%-80%. These drugs were injected, had many adverse effects, required frequent monitoring, and were often combined with oral ribavirin, which caused anemia. Treatment durations ranged up to 48 weeks.

Direct-acting anti-viral agents (DAAs) are antiviral drugs that act directly on hepatitis C multiplication.

Hepatitis C treatment is best discussed with a doctor or specialist familiar with current and developing options as this field is changing, and even major guidelines may become outdated quickly.

The latest treatment guidelines by the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) and Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) recommends use of DAAs as first-line treatment for hepatitis C infection. The choice of DAA varies by specific virus genotype, and the presence or absence of cirrhosis. In the U.S., specific insurance providers also might influence the choice due to the high cost of DAAs. Although the individual, public health, and cost benefits of treating all patients with hepatitis C is clear, the most difficult barrier to treating all people with HCV is the very high cost of the drug regimens. Patients are encouraged to discuss options with their health care professional.

Treatment is recommended in all patients with chronic hepatitis C unless they have a short life expectancy that is not related to liver disease. Severe life-threatening liver disease may require liver transplantation. Newer therapies with DAAs have allowed more and more patients to be treated.

The ultimate goals of antiviral therapy are to

A side goal is preventing co-infections with other hepatitis viruses, such as A and B, which can cause more liver disease than HCV alone. These can be prevented by vaccines and treatment.

When people first get hepatitis C, the infection is said to be acute. Most people with acute hepatitis C do not have symptoms so they are not recognized as being infected. However, some have low-grade fever, fatigue or other symptoms that lead to an early diagnosis. Others who become infected and have a known exposure to an infected source, such as a needlestick injury, are monitored closely.

Treatment decisions should be made on a case-by-case basis. Response to treatment is higher in acute hepatitis infection than chronic infection. However, many experts prefer to hold off treatment for 8-12 weeks to see whether the patient naturally eliminates the virus without treatment. Approaches to treatment are evolving. Patients with acute hepatitis C infection should discuss treatment options with a health care professional who is experienced in treating the disease. There is no established treatment regimen at this time.

If the hepatitis C RNA remains undetectable at the end of the treatment and follow-up period, this is called a sustained virologic response (SVR) and is considered a cure. Over 90% of people treated with DAAs are cured. These people have significantly reduced liver inflammation, and liver scarring may even be reversed.

About 5% of people who are treated for HCV infection are not cured by some of the older regimens. These people may still have options for cure with the newer regimens.

Few people with hepatitis C are at risk for problems if they are treated, however there are some factors that affect treatment regimens, such as concurrent HIV medications and kidney dysfunction. Some drugs are not safe for people with cirrhosis. Individuals who are unable to comply with the treatment schedule for psychological reasons or ongoing drug or alcohol abuse may not be good candidates for treatment because the drugs are very costly and require adherence to the pill regimen and regular follow-up visits. There are some important drug interactions with some of the medications that should be considered by the health care professional.

People with past hepatitis B or who have chronic active hepatitis B should not be treated for HCV without treating for HBV as well. As highly effective treatment for HCV has emerged, reports of serious hepatitis B have come to light. Similar to HCV, hepatitis B usually does not clear from the liver after acute infection, even though it is far less likely to cause chronic active hepatitis than hepatitis C infection. It remains dormant in most people, but it can reactivate with changes in the immune system. It is not clear why eliminating the HCV can allow the HBV infection to flare up. Hepatitis B screening is an important part of the hepatitis C evaluation. Those who have laboratory evidence of active or past infection with HBV should be monitored while receiving HCV treatment.

Compared to interferons and ribavirin drugs, the side effects of DAAs are far fewer and more tolerable. These side effects usually do not require discontinuation of therapy and are self-limiting after completion of therapy.

Patients with hepatitis B co-infection should be monitored for symptoms of reactivation of hepatitis, which are the same as the symptoms of acute hepatitis. The treating doctor may perform blood screening for this as well.

Hepatitis C is the leading reason for 40% to 45% of liver transplants in the U.S. Hepatitis C usually recurs after transplantation and infects the new liver. Approximately 25% of these patients with recurrent hepatitis will develop cirrhosis within five years of transplantation. Despite this, the five-year survival rate for patients with hepatitis C is similar to that of patients who are transplanted for other types of liver disease.

Most transplant centers delay therapy until recurrent hepatitis C in the transplanted liver is confirmed. Oral, highly effective, direct-acting antivirals have shown encouraging results in patients who have undergone liver transplantation for hepatitis C infection and have recurrent hepatitis C. The choice of therapy needs to be individualized and is rapidly evolving.

Once patients successfully complete treatment, the viral load after treatment determines if there is an SVR or cure. If cure is achieved (undetectable viral load after treatment), no further additional testing is recommended unless the patient has cirrhosis. Those who are not cured will need continued monitoring for progression of liver disease and its complications.

While cure eliminates worsening of fibrosis by hepatitis C, complications may still affect those with cirrhosis. These individuals still need regular screening for liver cancer as well as monitoring for esophageal varices that may bleed.

Because hepatitis B co-infection may reactivate or worsen even after treatment for HCV, monitoring for hepatitis symptoms may be needed after the end of therapy.

At this time there are no effective home or over-the-counter treatments for hepatitis C.

Over several years or decades, chronic inflammation may cause death of liver cells and cirrhosis (scaring, fibrosis). When the liver becomes cirrhotic, it becomes stiff, and it cannot perform its normal functions of clearing waste products from the blood. As fibrosis worsens, symptoms of liver failure begin to appear. This is called "decompensated cirrhosis " or "end-stage liver disease. " Symptoms of end-stage liver disease include:

The liver and spleen have an important function of clearing bacteria from the blood stream. Cirrhosis affects many areas of immune function, including attraction of white blood cells to bacteria, reduced killing of bacteria, reduced production of proteins involved in immune defenses, and decreased life span of white blood cells involved in immune defenses. This may be referred to as having cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction syndrome or CAIDS.

Transmission of hepatitis C can be prevented in several ways.

Prevention programs aim at needle sharing among drug addicts. Needle exchange programs and education have reduced transmission of hepatitis C infection. However, IV drug users are a difficult to reach population, and rates of hepatitis C remain high among them.

Among health care workers, safe needle-usage techniques have been developed to reduce accidental needlesticks. Newer needle systems prevent manual recapping of needles after use of syringes, which is a frequent cause of accidental needlesticks

There is no clear way to prevent hepatitis C transmission from mother to fetus at this time.

People with multiple sexual partners should use barrier precautions such as condoms to limit the risk of hepatitis C and other sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV.

If one partner is infected, monogamous couples may want to consider the low risk of transmission of hepatitis C infection when deciding whether to use condoms during sex. Some couples may decide to use them and some may not.

Screening of the blood supply has almost eliminated the risk of transmission of hepatitis C infection through transfusion.

People with hepatitis C infection should not share razors or toothbrushes with others because of the possibility that these items may be contaminated with blood.

People who want to get a body piercing(s) or tattoo(s) are encouraged to do so only at licensed piercing and tattoo shops (facilities), and verify that the body piercing or tattoo shop uses infection-control practices.

It is critical that physicians and clinics follow manufacturers and regulatory agency directions for sterilizing/cleaning instruments and that disposable instruments be discarded properly. There is no need to use special isolation procedures when dealing with hepatitis C infected patients.

In general, among patients with untreated hepatitis C:

Drinking alcohol and acquiring other hepatitis viruses are risk factors for worse liver disease. People with chronic hepatitis C should avoid drinking alcohol and should be screened for antibodies to hepatitis A and B. If they do not have antibodies, they should be vaccinated against these other hepatitis viruses.

People with hepatitis C should be educated about preventing HIV infection. Infection with both HIV and hepatitis C speeds up and worsens liver damage caused by hepatitis C. Hepatitis C also can affect the HIV infection and how it is treated. About 25% of people with HIV infection are co-infected (also infected) with hepatitis C, and up to 90% of IV drug users with HIV are co-infected with hepatitis C. Screening for hepatitis viruses is important in all people infected with HIV, just as screening for HIV is important in people who have hepatitis C.

Liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma, or hepatoma) is associated with cirrhosis from chronic hepatitis C. Some experts recommend screening patients with hepatitis C infection and cirrhosis for liver cancer periodically.

As our knowledge of hepatitis C increases, more and more patients are being diagnosed with chronic infection. Current research is very active and includes diagnosis, natural history, treatment, and vaccine development. Thus the field is constantly changing, with new guidelines added frequently.

Il modello matematico rivela il rischio di infezione da SARS-CoV-2 dopo il trapianto di microbiota fecale

Il modello matematico rivela il rischio di infezione da SARS-CoV-2 dopo il trapianto di microbiota fecale

Colite:sintomi, tipi, dieta e trattamento

Colite:sintomi, tipi, dieta e trattamento

Incontra i gemelli Mac, fondatori di The Gut Stuff

Incontra i gemelli Mac, fondatori di The Gut Stuff

Malattia infiammatoria intestinale (IBD)

Malattia infiammatoria intestinale (IBD)

Amici di una dieta specifica con carboidrati in evidenza:Susan "The SCD Girl"

Amici di una dieta specifica con carboidrati in evidenza:Susan "The SCD Girl"

Che cos'è una cromoendoscopia?

Che cos'è una cromoendoscopia?

Come fai a sapere se hai sintomi di emorroidi o qualcosa di più grave?

Cosa sono le emorroidi? Le piccole macchie di sangue possono essere un sintomo di emorroidi, ma se cè sangue più consistente che appare durante i movimenti intestinali, potrebbe essere un segno di

Come fai a sapere se hai sintomi di emorroidi o qualcosa di più grave?

Cosa sono le emorroidi? Le piccole macchie di sangue possono essere un sintomo di emorroidi, ma se cè sangue più consistente che appare durante i movimenti intestinali, potrebbe essere un segno di

Perché la maggior parte delle persone non riesce a stare bene

Era il 2008 e stavo di nuovo piangendo in un bagno al lavoro. Il mio capo mi chiamava con il walkie-talkie, arrabbiato perché non li stavo aiutando a riparare un guasto critico della macchina nellimpi

Perché la maggior parte delle persone non riesce a stare bene

Era il 2008 e stavo di nuovo piangendo in un bagno al lavoro. Il mio capo mi chiamava con il walkie-talkie, arrabbiato perché non li stavo aiutando a riparare un guasto critico della macchina nellimpi

Il microbioma intestinale è una realtà anche nella vita fetale

Uno studio pubblicato su Journal of Clinical Investigation mostra che sia nei topi che nelluomo, lintestino fetale ha il suo microbioma, che probabilmente deriva direttamente dallorganismo materno.

Il microbioma intestinale è una realtà anche nella vita fetale

Uno studio pubblicato su Journal of Clinical Investigation mostra che sia nei topi che nelluomo, lintestino fetale ha il suo microbioma, che probabilmente deriva direttamente dallorganismo materno.