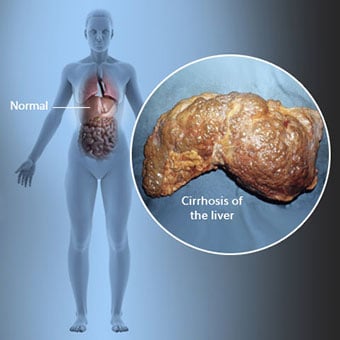

La cirrosi è una complicanza della malattia epatica che comporta la perdita di cellule epatiche e cicatrici irreversibili del fegato.

La cirrosi è una complicanza della malattia epatica che comporta la perdita di cellule epatiche e cicatrici irreversibili del fegato. Gli individui con cirrosi possono avere pochi o nessun sintomo e segno di malattia del fegato. Alcuni dei sintomi possono essere aspecifici, cioè non suggeriscono che il fegato sia la loro causa. Alcuni dei sintomi e segni più comuni di cirrosi includono:

Gli individui con cirrosi sviluppano anche sintomi e segni dalle complicanze della cirrosi.

Esistono molte cause di cirrosi tra cui sostanze chimiche (come alcol, grassi e alcuni farmaci), virus, sostanze tossiche metalli e malattie autoimmuni del fegato in cui il sistema immunitario del corpo attacca il fegato.

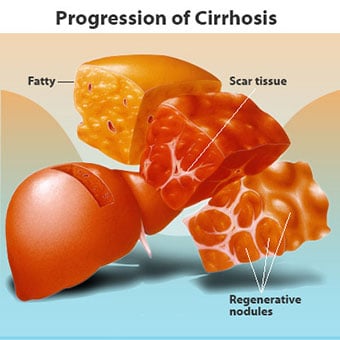

Esistono molte cause di cirrosi tra cui sostanze chimiche (come alcol, grassi e alcuni farmaci), virus, sostanze tossiche metalli e malattie autoimmuni del fegato in cui il sistema immunitario del corpo attacca il fegato. La cirrosi è una complicazione di molte malattie del fegato caratterizzate da una struttura e una funzione anormali del fegato. Le malattie che portano alla cirrosi lo fanno perché danneggiano e uccidono le cellule del fegato, dopodiché l'infiammazione e la riparazione associate alle cellule epatiche morenti provocano la formazione di tessuto cicatriziale. Le cellule del fegato che non muoiono si moltiplicano nel tentativo di sostituire le cellule che sono morte. Ciò si traduce in gruppi di cellule epatiche di nuova formazione (noduli rigenerativi) all'interno del tessuto cicatriziale. Esistono molte cause di cirrosi tra cui sostanze chimiche (come alcol, grassi e alcuni farmaci), virus, metalli tossici (come ferro e rame che si accumulano nel fegato a causa di malattie genetiche) e malattie autoimmuni del fegato in cui il il sistema immunitario del corpo attacca il fegato.

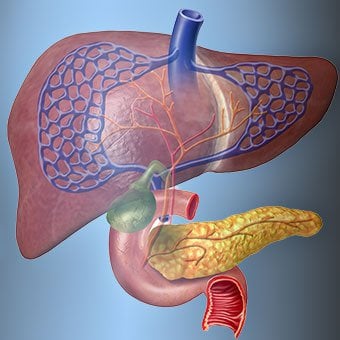

Il rapporto del fegato con il sangue è unico.

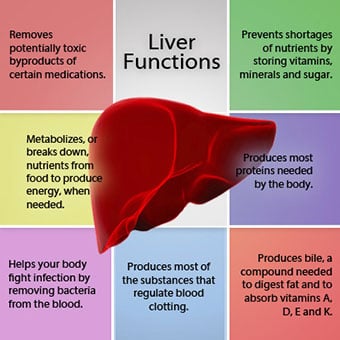

Il rapporto del fegato con il sangue è unico. Il fegato è un organo importante nel corpo. Svolge molte funzioni critiche, due delle quali sono la produzione di sostanze necessarie all'organismo, ad esempio le proteine della coagulazione necessarie per la coagulazione del sangue e la rimozione di sostanze tossiche che possono essere dannose per l'organismo, ad esempio i farmaci . Il fegato ha anche un ruolo importante nella regolazione dell'apporto di glucosio (zucchero) e lipidi (grassi) che l'organismo utilizza come combustibile. Per svolgere queste funzioni critiche, le cellule epatiche devono funzionare normalmente e devono essere molto vicine al sangue perché le sostanze che vengono aggiunte o rimosse dal fegato vengono trasportate da e verso il fegato dal sangue.

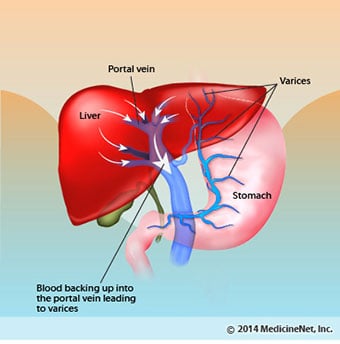

Il rapporto del fegato con il sangue è unico. A differenza della maggior parte degli organi del corpo, solo una piccola quantità di sangue viene fornita al fegato dalle arterie. La maggior parte dell'apporto di sangue al fegato proviene dalle vene intestinali mentre il sangue ritorna al cuore. La vena principale che restituisce il sangue dall'intestino è chiamata vena porta. Quando la vena porta passa attraverso il fegato, si rompe in vene sempre più piccole. Le vene più piccole (chiamate sinusoidi per la loro struttura unica) sono a stretto contatto con le cellule del fegato. Le cellule del fegato si allineano lungo la lunghezza delle sinusoidi. Questa stretta relazione tra le cellule del fegato e il sangue della vena porta consente alle cellule del fegato di rimuovere e aggiungere sostanze al sangue. Una volta che il sangue è passato attraverso le sinusoidi, viene raccolto in vene sempre più grandi che alla fine formano un'unica vena, la vena epatica, che restituisce il sangue al cuore.

Nella cirrosi, la relazione tra sangue e cellule epatiche viene distrutta. Anche se le cellule epatiche che sopravvivono o si sono appena formate possono essere in grado di produrre e rimuovere sostanze dal sangue, non hanno la normale relazione intima con il sangue e questo interferisce con la capacità delle cellule epatiche di aggiungere o rimuovere sostanze dal sangue. Inoltre, le cicatrici all'interno del fegato cirrotico ostruiscono il flusso di sangue attraverso il fegato e verso le cellule del fegato. Come risultato dell'ostruzione al flusso di sangue attraverso il fegato, il sangue "arretra" nella vena porta e la pressione nella vena porta aumenta, una condizione chiamata ipertensione portale. A causa dell'ostruzione al flusso e delle alte pressioni nella vena porta, il sangue nella vena porta cerca altre vene in cui tornare al cuore, vene con pressioni inferiori che bypassano il fegato. Sfortunatamente, il fegato non è in grado di aggiungere o rimuovere sostanze dal sangue che lo bypassano. È una combinazione di numero ridotto di cellule epatiche, perdita del normale contatto tra il sangue che passa attraverso il fegato e le cellule epatiche e sangue che bypassa il fegato che porta a molti dei segni della cirrosi.

Un secondo motivo per i problemi causati dalla cirrosi è il rapporto disturbato tra le cellule del fegato ei canali attraverso i quali scorre la bile. La bile è un fluido prodotto dalle cellule del fegato che svolge due importanti funzioni:favorire la digestione e rimuovere ed eliminare le sostanze tossiche dall'organismo. La bile prodotta dalle cellule epatiche viene secreta in canali molto piccoli che scorrono tra le cellule epatiche che rivestono le sinusoidi, chiamati canalicoli. I canalicoli si svuotano in piccoli condotti che poi si uniscono per formare condotti sempre più grandi. Tutti i condotti si combinano in un condotto che entra nell'intestino tenue dove può aiutare con la digestione del cibo. Allo stesso tempo, le sostanze tossiche contenute nella bile entrano nell'intestino e poi vengono eliminate con le feci. Nella cirrosi, i canalicoli sono anormali e la relazione tra cellule epatiche e canalicoli viene distrutta, proprio come la relazione tra cellule epatiche e sangue nei sinusoidi. Di conseguenza, il fegato non è in grado di eliminare normalmente le sostanze tossiche e possono accumularsi nel corpo. In misura minore, anche la digestione nell'intestino è ridotta.

I sintomi ei segni comuni di cirrosi includono ittero, affaticamento, debolezza, perdita di appetito, prurito e facile formazione di lividi.

I sintomi ei segni comuni di cirrosi includono ittero, affaticamento, debolezza, perdita di appetito, prurito e facile formazione di lividi. Le persone con cirrosi possono avere pochi o nessun sintomo e segno di malattia del fegato. Alcuni dei sintomi possono essere aspecifici e non suggeriscono che il fegato sia la loro causa. I sintomi e i segni comuni di cirrosi includono:

Le persone con cirrosi se il fegato sviluppa anche sintomi e segni dalle complicanze della malattia.

La cirrosi di per sé è già una fase avanzata del danno epatico. Nelle prime fasi della malattia del fegato ci sarà un'infiammazione del fegato. Se questa infiammazione non viene trattata può portare a cicatrici (fibrosi). In questa fase è ancora possibile che il fegato guarisca con il trattamento.

Se la fibrosi del fegato non viene trattata, può causare cirrosi. In questa fase, il tessuto cicatriziale non può guarire, ma la progressione della cicatrizzazione può essere prevenuta o rallentata. Le persone con cirrosi che presentano segni di complicanze possono sviluppare una malattia epatica allo stadio terminale (ESLD) e l'unico trattamento in questa fase è il trapianto di fegato.

Complicazioni di edema, ascite e peritonite batterica

Complicazioni di edema, ascite e peritonite batterica Quando la cirrosi epatica diventa grave, i segnali vengono inviati ai reni per trattenere il sale e l'acqua nel corpo. Il sale e l'acqua in eccesso si accumulano prima nel tessuto sotto la pelle delle caviglie e delle gambe a causa dell'effetto della gravità quando si è in piedi o seduti. Questo accumulo di liquido è chiamato edema periferico o edema da vaiolatura. (L'edema da vaiolatura si riferisce al fatto che premere con decisione un polpastrello contro una caviglia o una gamba con edema provoca una rientranza nella pelle che persiste per qualche tempo dopo il rilascio della pressione. Qualsiasi tipo di pressione, ad esempio dall'elastico di un calzino , può essere sufficiente a causare pitting.) Il gonfiore spesso peggiora alla fine della giornata dopo essere stati in piedi o seduti e può diminuire durante la notte quando si è sdraiati. Man mano che la cirrosi peggiora e viene trattenuta una quantità maggiore di sale e acqua, il liquido può accumularsi anche nella cavità addominale tra la parete addominale e gli organi addominali (chiamati ascite) causando gonfiore dell'addome, fastidio addominale e aumento di peso.

Il liquido nella cavità addominale (ascite) è il luogo perfetto per la crescita dei batteri. Normalmente, la cavità addominale contiene una quantità molto piccola di liquido che può resistere bene alle infezioni e i batteri che entrano nell'addome (di solito dall'intestino) vengono uccisi o trovano la loro strada nella vena porta e nel fegato dove vengono uccisi. Nella cirrosi, il liquido che si raccoglie nell'addome non è in grado di resistere normalmente all'infezione. Inoltre, più batteri si fanno strada dall'intestino all'ascite. È probabile che si verifichi un'infezione all'interno dell'addome e dell'ascite, chiamata peritonite batterica spontanea o SBP. La SBP è una complicanza pericolosa per la vita. Alcuni pazienti con SBP non hanno sintomi, mentre altri hanno febbre, brividi, dolore e dolorabilità addominali, diarrea e ascite in peggioramento.

Complicanze di sanguinamento e milza

Complicanze di sanguinamento e milza Nel fegato cirrotico, il tessuto cicatriziale blocca il flusso di sangue che ritorna al cuore dall'intestino e aumenta la pressione nella vena porta (ipertensione portale). Quando la pressione nella vena porta diventa sufficientemente alta, fa fluire il sangue intorno al fegato attraverso le vene con pressione più bassa per raggiungere il cuore. Le vene più comuni attraverso le quali il sangue bypassa il fegato sono le vene che rivestono la parte inferiore dell'esofago e la parte superiore dello stomaco.

Come risultato dell'aumento del flusso sanguigno e del conseguente aumento della pressione, le vene nell'esofago inferiore e nella parte superiore dello stomaco si espandono e quindi vengono denominate varici esofagee e gastriche; maggiore è la pressione portale, più grandi sono le varici e più è probabile che un paziente sanguini dalle varici nell'esofago o nello stomaco.

Il sanguinamento da varici è grave e senza un trattamento immediato può essere fatale. I sintomi dell'emorragia da varici includono vomito di sangue (può apparire come sangue rosso mescolato a coaguli o "fondi di caffè"), feci che sono nere e catramose a causa di cambiamenti nel sangue mentre attraversa l'intestino (melena) e ortostasi vertigini o svenimenti (causati da un calo della pressione sanguigna soprattutto quando ci si alza da una posizione sdraiata).

Il sanguinamento può verificarsi raramente da varici che si formano altrove nell'intestino, ad esempio il colon. I pazienti ricoverati in ospedale a causa di varici esofagee sanguinanti attivamente hanno un alto rischio di sviluppare peritonite batterica spontanea, anche se le ragioni di ciò non sono ancora chiare.

La milza normalmente funge da filtro per rimuovere i globuli rossi, i globuli bianchi e le piastrine (piccole particelle importanti per la coagulazione del sangue). Il sangue che drena dalla milza si unisce al sangue nella vena porta dall'intestino. Quando la pressione nella vena porta aumenta nella cirrosi, blocca sempre più il flusso di sangue dalla milza. Il sangue "fa il backup", accumulandosi nella milza, e la milza si gonfia di dimensioni, una condizione chiamata splenomegalia. A volte, la milza è così ingrossata da causare dolore addominale.

Man mano che la milza si ingrandisce, filtra sempre più cellule del sangue e piastrine finché il loro numero nel sangue non si riduce. L'ipersplenismo è il termine usato per descrivere questa condizione ed è associato a un basso numero di globuli rossi (anemia), basso numero di globuli bianchi (leucopenia) e/o basso numero di piastrine (trombocitopenia). L'anemia può causare debolezza, la leucopenia può portare a infezioni e la trombocitopenia può compromettere la coagulazione del sangue e provocare sanguinamento prolungato

Complicanze epatiche (epatiche)

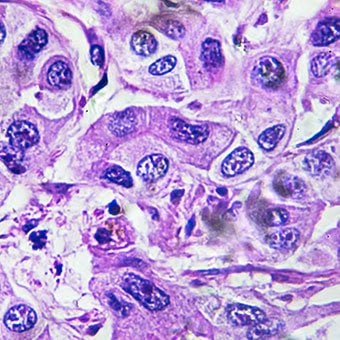

Complicanze epatiche (epatiche) La cirrosi dovuta a qualsiasi causa aumenta il rischio di cancro primario del fegato (carcinoma epatocellulare). Primario si riferisce al fatto che il tumore ha origine nel fegato. Un cancro al fegato secondario è quello che ha origine in altre parti del corpo e si diffonde (metastatizza) al fegato.

I sintomi e i segni più comuni del carcinoma epatico primario sono dolore e gonfiore addominale, ingrossamento del fegato, perdita di peso e febbre. Inoltre, i tumori del fegato possono produrre e rilasciare una serie di sostanze, comprese quelle che causano un aumento della conta dei globuli rossi (eritrocitosi), bassi livelli di zucchero nel sangue (ipoglicemia) e livelli elevati di calcio nel sangue (ipercalcemia).

Alcune delle proteine del cibo che sfuggono alla digestione e all'assorbimento vengono utilizzate dai batteri che sono normalmente presenti nell'intestino. Mentre usano la proteina per i propri scopi, i batteri producono sostanze che rilasciano nell'intestino per poi essere assorbite dal corpo. Alcune di queste sostanze, come l'ammoniaca, possono avere effetti tossici sul cervello. Normalmente, queste sostanze tossiche vengono trasportate dall'intestino nella vena porta al fegato dove vengono rimosse dal sangue e disintossicate.

Quando è presente la cirrosi, le cellule epatiche non possono funzionare normalmente perché sono danneggiate o perché hanno perso la loro normale relazione con il sangue. Inoltre, parte del sangue nella vena porta bypassa il fegato attraverso altre vene. Il risultato di queste anomalie è che le sostanze tossiche non possono essere rimosse dalle cellule del fegato e invece si accumulano nel sangue.

Quando le sostanze tossiche si accumulano a sufficienza nel sangue, la funzione del cervello è compromessa, una condizione chiamata encefalopatia epatica. Dormire durante il giorno piuttosto che di notte (inversione del normale schema del sonno) è un sintomo precoce dell'encefalopatia epatica. Altri sintomi includono irritabilità, incapacità di concentrarsi o eseguire calcoli, perdita di memoria, confusione o livelli di coscienza depressi. In definitiva, l'encefalopatia epatica grave provoca coma e morte.

Le sostanze tossiche rendono inoltre il cervello dei pazienti con cirrosi molto sensibile ai farmaci che normalmente vengono filtrati e disintossicati dal fegato. Potrebbe essere necessario ridurre le dosi di molti farmaci per evitare un accumulo di sostanze tossiche nella cirrosi, in particolare sedativi e farmaci usati per favorire il sonno. In alternativa, possono essere utilizzati farmaci che non necessitano di essere disintossicati o eliminati dall'organismo dal fegato, come i farmaci eliminati dai reni.

I pazienti con cirrosi in peggioramento possono sviluppare la sindrome epatorenale. Questa sindrome è una grave complicanza in cui la funzione dei reni è ridotta. È un problema funzionale nei reni, il che significa che non ci sono danni fisici ai reni. Invece, la funzione ridotta è dovuta ai cambiamenti nel modo in cui il sangue scorre attraverso i reni stessi. La sindrome epatorenale è definita come l'incapacità progressiva dei reni di eliminare le sostanze dal sangue e di produrre quantità adeguate di urina mentre vengono mantenute altre importanti funzioni del rene, come la ritenzione di sale. Se la funzionalità epatica migliora o un fegato sano viene trapiantato in un paziente con sindrome epatorenale, i reni di solito ricominciano a funzionare normalmente. Ciò suggerisce che la ridotta funzionalità dei reni è il risultato dell'accumulo di sostanze tossiche nel sangue o della funzionalità epatica anormale quando il fegato si guasta. Esistono due tipi di sindrome epatorenale. Un tipo si verifica gradualmente nel corso dei mesi. L'altro si verifica rapidamente nell'arco di una o due settimane.

Raramente, alcuni pazienti con cirrosi avanzata possono sviluppare la sindrome epatopolmonare. Questi pazienti possono avere difficoltà a respirare perché alcuni ormoni rilasciati nella cirrosi avanzata causano un funzionamento anomalo dei polmoni. Il problema di base nel polmone è che non scorre abbastanza sangue attraverso i piccoli vasi sanguigni nei polmoni che sono in contatto con gli alveoli (sacche d'aria) dei polmoni. Il sangue che scorre attraverso i polmoni viene deviato attorno agli alveoli e non può raccogliere abbastanza ossigeno dall'aria negli alveoli. Di conseguenza, il paziente avverte mancanza di respiro, in particolare con lo sforzo.

Esistono 12 cause comuni di cirrosi.

Esistono 12 cause comuni di cirrosi. Cause comuni di cirrosi epatica includono:

Cause meno comuni di cirrosi includono:

In alcune parti del mondo (in particolare il Nord Africa), l'infezione del fegato da un parassita (schistosomiasi) è la causa più comune di malattie epatiche e cirrosi.

Alcohol and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease are common causes of cirrhosis.

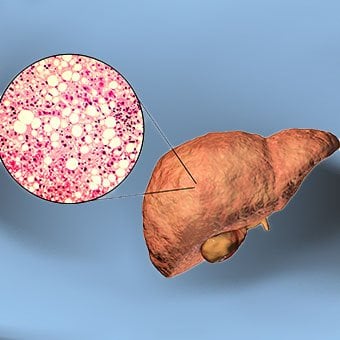

Alcohol and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease are common causes of cirrhosis. Alcohol is a very common cause of cirrhosis, particularly in the Western world. Chronic, high levels of alcohol consumption injure liver cells. Thirty percent of individuals who drink daily at least eight to sixteen ounces of hard liquor or the equivalent for fifteen or more years will develop cirrhosis. Alcohol causes a range of liver diseases, which include simple and uncomplicated fatty liver (steatosis), more serious fatty liver with inflammation (steatohepatitis or alcoholic hepatitis), and cirrhosis.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) refers to a wide spectrum of liver diseases that, like alcoholic liver disease, range from simple steatosis, to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), to cirrhosis. All stages of NAFLD have in common the accumulation of fat in liver cells. The term nonalcoholic is used because NAFLD occurs in individuals who do not consume excessive amounts of alcohol, yet in many respects the microscopic picture of NAFLD is similar to what can be seen in liver disease that is due to excessive alcohol. NAFLD is associated with a condition called insulin resistance, which, in turn, is associated with metabolic syndrome and diabetes mellitus type 2. Obesity is the main cause of insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes. NAFLD is the most common liver disease in the United States and is responsible for up to 25% of all liver disease. The number of livers transplanted for NAFLD-related cirrhosis is on the rise. Public health officials are worried that the current epidemic of obesity will dramatically increase the development of NAFLD and cirrhosis in the population.

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a liver disease caused by an abnormality of the immune system that is found predominantly in women.

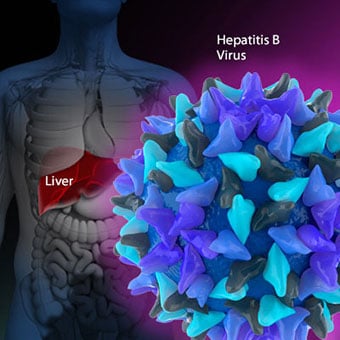

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a liver disease caused by an abnormality of the immune system that is found predominantly in women. Chronic viral hepatitis is a condition in which hepatitis B or hepatitis C virus infects the liver for years. Most patients with viral hepatitis will not develop chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis. The majority of patients infected with hepatitis A recover completely within weeks, without developing chronic infection. In contrast, some patients infected with hepatitis B virus and most patients infected with hepatitis C virus develop chronic hepatitis, which, in turn, causes progressive liver damage and leads to cirrhosis, and, sometimes, liver cancers.

Autoimmune hepatitis is a liver disease found more commonly in women that is caused by an abnormality of the immune system. The abnormal immune activity in autoimmune hepatitis causes progressive inflammation and destruction of liver cells (hepatocytes), leading ultimately to cirrhosis.

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a liver disease caused by an abnormality of the immune system that is found predominantly in women. The abnormal immunity in PBC causes chronic inflammation and destruction of the small bile ducts within the liver. The bile ducts are passages within the liver through which bile travels to the intestine. Bile is a fluid produced by the liver that contains substances required for digestion and absorption of fat in the intestine, as well as other compounds that are waste products, such as the pigment bilirubin. (Bilirubin is produced by the breakdown of hemoglobin from old red blood cells.). Along with the gallbladder, the bile ducts make up the biliary tract. In PBC, the destruction of the small bile ducts blocks the normal flow of bile into the intestine. As the inflammation continues to destroy more of the bile ducts, it also spreads to destroy nearby liver cells. As the destruction of the hepatocytes proceeds, scar tissue (fibrosis) forms and spreads throughout the areas of destruction. The combined effects of progressive inflammation, scarring, and the toxic effects of accumulating waste products culminates in cirrhosis.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is an uncommon disease frequently found in patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. In PSC, the large bile ducts outside of the liver become inflamed, narrowed, and obstructed. Obstruction to the flow of bile leads to infections of the bile ducts and jaundice, eventually causing cirrhosis. In some patients, injury to the bile ducts (usually because of surgery) also can cause obstruction and cirrhosis of the liver.

Different liver diseases should be diagnosed by specialists and different tests such as liver blood test, biopsy, and others.

Different liver diseases should be diagnosed by specialists and different tests such as liver blood test, biopsy, and others. Inherited (genetic) disorders that result in the accumulation of toxic substances in the liver, which leads to tissue damage and cirrhosis. Examples include the abnormal accumulation of iron (hemochromatosis) or copper (Wilson disease). In hemochromatosis, patients inherit a tendency to absorb an excessive amount of iron from food. Over time, iron accumulation in different organs throughout the body causes cirrhosis, arthritis, heart muscle damage leading to heart failure, and testicular dysfunction causing loss of sexual drive. Treatment is aimed at preventing damage to organs by removing iron from the body through phlebotomy (removing blood). In Wilson disease, there is an inherited abnormality in one of the proteins that control copper in the body. Over time, copper accumulates in the liver, eyes, and brain. Cirrhosis, tremor, psychiatric disturbances, and other neurological difficulties occur if the condition is not treated early. Treatment is with oral medication, which increases the amount of copper that is eliminated from the body in the urine.

Cryptogenic cirrhosis (cirrhosis due to unidentified causes) is a common reason for liver transplantation. It is termed called cryptogenic cirrhosis because for many years doctors have been being unable to explain why a proportion of patients developed cirrhosis. Doctors now believe that cryptogenic cirrhosis is due to NASH (nonalcoholic steatohepatitis) caused by long-standing obesity, type 2 diabetes, and insulin resistance. The fat in the liver of patients with NASH is believed to disappear with the onset of cirrhosis, and this has made it difficult for doctors to make the connection between NASH and cryptogenic cirrhosis for a long time. One important clue that NASH leads to cryptogenic cirrhosis is the finding of a high occurrence of NASH in the new livers of patients undergoing liver transplant for cryptogenic cirrhosis. Finally, a study from France suggests that patients with NASH have a similar risk of developing cirrhosis as patients with long-standing infection with hepatitis C virus. (See discussion that follows.) However, the progression to cirrhosis from NASH is thought to be slow and the diagnosis of cirrhosis typically is made in people in their sixties.

Infants can be born without bile ducts (biliary atresia) and ultimately develop cirrhosis. Other infants are born lacking vital enzymes for controlling sugars that lead to the accumulation of sugars and cirrhosis. On rare occasions, the absence of a specific enzyme can cause cirrhosis and scarring of the lung (alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency).

Less common causes of cirrhosis include unusual reactions to some drugs and prolonged exposure to toxins, as well as chronic heart failure (cardiac cirrhosis). In certain parts of the world (particularly Northern Africa), infection of the liver with a parasite (schistosomiasis) is the most common cause of liver disease and cirrhosis.

Different liver diseases should be diagnosed by specialists and different tests such as liver blood test, biopsy, and others.

Different liver diseases should be diagnosed by specialists and different tests such as liver blood test, biopsy, and others. The single best test for diagnosing cirrhosis is a biopsy of the liver. Liver biopsies carry a small risk for serious complications, and biopsy often is reserved for those patients in whom the diagnosis of the type of liver disease or the presence of cirrhosis is not clear. The history, physical examination, or routine testing may suggest the possibility of cirrhosis. If cirrhosis is present, other tests can be used to determine the severity of the cirrhosis and the presence of complications. Tests also may be used to diagnose the underlying disease that is causing the cirrhosis. Examples of how doctors diagnose and evaluate cirrhosis are:

There are four types of treatment of cirrhosis.

There are four types of treatment of cirrhosis. Treatment of cirrhosis includes

Consume a balanced diet and one multivitamin daily. Patients with PBC with impaired absorption of fat-soluble vitamins may need additional vitamins D and K.

Avoid drugs (including alcohol) that cause liver damage. All patients with cirrhosis should avoid alcohol. Most patients with alcohol-induced cirrhosis experience an improvement in liver function with abstinence from alcohol. Even patients with chronic hepatitis B and C can substantially reduce liver damage and slow the progression towards cirrhosis with abstinence from alcohol.

Avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, e.g., ibuprofen). Patients with cirrhosis can experience worsening of liver and kidney function with NSAIDs.

Eradicate hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus by using anti-viral medications. Not all patients with cirrhosis due to chronic viral hepatitis are candidates for drug treatment. Some patients may experience serious deterioration in liver function and/or intolerable side effects during treatment. Thus, decisions to treat viral hepatitis have to be individualized, after consulting with doctors experienced in treating liver diseases (hepatologists).

Remove blood from patients with hemochromatosis to reduce the levels of iron and prevent further damage to the liver. In Wilson's disease, medications can be used to increase the excretion of copper in the urine to reduce the levels of copper in the body and prevent further damage to the liver.

Suppress the immune system with drugs such as prednisone and azathioprine (Imuran) to decrease inflammation of the liver in autoimmune hepatitis.

Treat patients with PBC with a bile acid preparation, ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), also called ursodiol (Actigall). Results of an analysis that combined the results from several clinical trials showed that UDCA increased survival among PBC patients during 4 years of therapy. The development of portal hypertension also was reduced by the UDCA. It is important to note that despite producing clear benefits, UDCA treatment primarily retards progression and does not cure PBC. Other medications such as colchicine and methotrexate also may have benefits in subsets of patients with PBC.

Immunize patients with cirrhosis against infection with hepatitis A and B to prevent a serious deterioration in liver. There are currently no vaccines available for immunizing against hepatitis C.

Treatment for edema, ascites, and hypersplenism complications.

Treatment for edema, ascites, and hypersplenism complications. Retaining salt and water can lead to swelling of the ankles and legs (edema) or abdomen (ascites) in patients with cirrhosis. Doctors often advise patients with cirrhosis to restrict dietary salt (sodium) and fluid to decrease edema and ascites. The amount of salt in the diet usually is restricted to 2 grams per day and fluid to 1.2 liters per day. In most patients with cirrhosis, salt and fluid restriction is not enough and diuretics have to be added.

Diuretics are medications that work in the kidneys to promote the elimination of salt and water into the urine. A combination of the diuretics spironolactone (Aldactone) and furosemide (Lasix) can reduce or eliminate the edema and ascites in most patients. During treatment with diuretics, it is important to monitor the function of the kidneys by measuring blood levels of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine to determine if too much diuretic is being used. Too much diuretic can lead to kidney dysfunction that is reflected in elevations of the BUN and creatinine levels in the blood.

Sometimes, when the diuretics do not work (in which case the ascites is said to be refractory), a long needle or catheter is used to draw out the ascitic fluid directly from the abdomen, a procedure called abdominal paracentesis. It is common to withdraw large amounts (liters) of fluid from the abdomen when the ascites is causing painful abdominal distension and/or difficulty breathing because it limits the movement of the diaphragms.

Another treatment for refractory ascites is a procedure called transjugular intravenous portosystemic shunting (TIPS).

The spleen normally acts as a filter to remove older red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets (small particles important for the clotting of blood). The blood that drains from the spleen joins the blood in the portal vein from the intestines. As the pressure in the portal vein rises in cirrhosis, it increasingly blocks the flow of blood from the spleen. The blood "backs-up," accumulating in the spleen, and the spleen swells in size, a condition referred to as splenomegaly. Sometimes, the spleen is so enlarged it causes abdominal pain.

As the spleen enlarges, it filters out more and more of the blood cells and platelets until their numbers in the blood are reduced. Hypersplenism is the term used to describe this condition, and it is associated with a low red blood cell count (anemia), low white blood cell count (leukopenia), and/or a low platelet count (thrombocytopenia). Anemia can cause weakness, leucopenia can lead to infections, and thrombocytopenia can impair the clotting of blood and result in prolonged bleeding.

Once varices have bled, they tend to rebleed and the probability that a patient will die from each bleeding episode is high (30% to 35%). Treatment is necessary to prevent the first bleeding episode as well as rebleeding.

Once varices have bled, they tend to rebleed and the probability that a patient will die from each bleeding episode is high (30% to 35%). Treatment is necessary to prevent the first bleeding episode as well as rebleeding. If large varices develop in the esophagus or upper stomach, patients with cirrhosis are at risk for serious bleeding due to rupture of these varices. Once varices have bled, they tend to rebleed and the probability that a patient will die from each bleeding episode is high (30% to 35%). Treatment is necessary to prevent the first bleeding episode as well as rebleeding. Treatments include medications and procedures to decrease the pressure in the portal vein and procedures to destroy the varices.

Hepatic encephalopathy usually should be treated with a low protein diet and oral lactulose.

Hepatic encephalopathy usually should be treated with a low protein diet and oral lactulose. Patients with an abnormal sleep cycle, impaired thinking, odd behavior, or other signs of hepatic encephalopathy usually should be treated with a low protein diet and oral lactulose. Dietary protein is restricted because it is a source of toxic compounds that cause hepatic encephalopathy. Lactulose, which is a liquid, traps toxic compounds in the colon so they cannot be absorbed into the bloodstream, and thus cause encephalopathy. Lactulose is converted to lactic acid in the colon, and the acidic environment that results is believed to trap the toxic compounds produced by the bacteria. To be sure adequate lactulose is present in the colon at all times, the patient should adjust the dose to produce 2 to 3 semiformed bowel movements a day. Lactulose is a laxative, and the effectiveness of treatment can be judged by loosening or increasing the frequency of stools. Rifaximin (Xifaxan) is an antibiotic taken orally that is not absorbed into the body but rather remains in the intestines. It is the preferred mode of treatment of hepatic encephalopathy. Antibiotics work by suppressing the bacteria that produce the toxic compounds in the colon.

Most patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis are hospitalized and treated with intravenous antibiotics.

Most patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis are hospitalized and treated with intravenous antibiotics. Patients suspected of having spontaneous bacterial peritonitis usually will undergo paracentesis. The fluid that is removed is examined for white blood cells and cultured for bacteria. Culturing involves inoculating a sample of the ascites into a bottle of nutrient-rich fluid that encourages the growth of bacteria, thus facilitating the identification of even small numbers of bacteria. Blood and urine samples also are often obtained for culturing because many patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis also will have infections in their blood and urine. Many doctors believe the infection may have begun in the blood and the urine and spread to the ascitic fluid to cause spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Most patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis are hospitalized and treated with intravenous antibiotics such as cefotaxime (Claforan). Patients usually treated with antibiotics include:

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is a serious infection. It often occurs in patients with advanced cirrhosis whose immune systems are weak, but with modern antibiotics and early detection and treatment, the prognosis of recovering from an episode of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is good.

In some patients, oral antibiotics (norfloxacin [Noroxin] or sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim [Bactrim]) can be prescribed to prevent spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Not all patients with cirrhosis and ascites should be treated with antibiotics to prevent spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, but some patients are at high risk for developing spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and warrant preventive treatment.

The prognosis and life expectancy for cirrhosis of the liver varies and depends on the cause, the severity, any complications, and any underlying diseases.

The prognosis and life expectancy for cirrhosis of the liver varies and depends on the cause, the severity, any complications, and any underlying diseases. Several types of liver disease that cause cirrhosis (such as hepatitis B and C) are associated with a high incidence of liver cancer. It is useful to screen for liver cancer in patients with cirrhosis, as early surgical treatment or transplantation of the liver can cure the patient of cancer. The difficulty is that the methods available for screening are only partially effective, identifying at best only half of patients at a curable stage of their cancer. Despite the partial effectiveness of screening, most patients with cirrhosis, particularly hepatitis B and C, are screened yearly or every six months with ultrasound examination of the liver and measurements of cancer-produced proteins in the blood, for example, alpha-fetoprotein.

Cirrhosis is irreversible. Liver function usually gradually worsens despite treatment, and complications of cirrhosis increase and become difficult to treat. When cirrhosis is far advanced liver transplantation often is the only option for treatment. Recent advances in surgical transplantation and medications to prevent infection and rejection of the transplanted liver have greatly improved survival after transplantation. On average, more than 80% of patients who receive transplants are alive after five years. Not everyone with cirrhosis is a candidate for transplantation. Furthermore, there is a shortage of livers to transplant, and they're usually is a long (months to years) wait before a liver for transplanting becomes available. Measures to slow the progression of liver disease, and treat and prevent complications of cirrhosis are vitally important.

The prognosis and life expectancy for cirrhosis of the liver varies and depends on the cause, the severity, any complications, and any underlying diseases.

Progress in the management and prevention of cirrhosis continues. Research is ongoing to determine the mechanism of scar formation in the liver and how this process of scarring can be interrupted or even reversed. Newer and better treatments for viral liver disease are being developed to prevent the progression to cirrhosis. Prevention of viral hepatitis by vaccination, which is available for hepatitis B, is being developed for hepatitis C. Treatments for the complications of cirrhosis are being developed or revised, and tested continually. Finally, research is being directed at identifying new proteins in the blood that can detect liver cancer early or predict which patients will develop liver cancer.

Il virus Ebola è contagioso?

Il virus Ebola è contagioso?

13 strumenti per mantenersi in salute durante il viaggio

13 strumenti per mantenersi in salute durante il viaggio

Le diete a base vegetale possono aiutare a proteggere dalle malattie cardiache?

Le diete a base vegetale possono aiutare a proteggere dalle malattie cardiache?

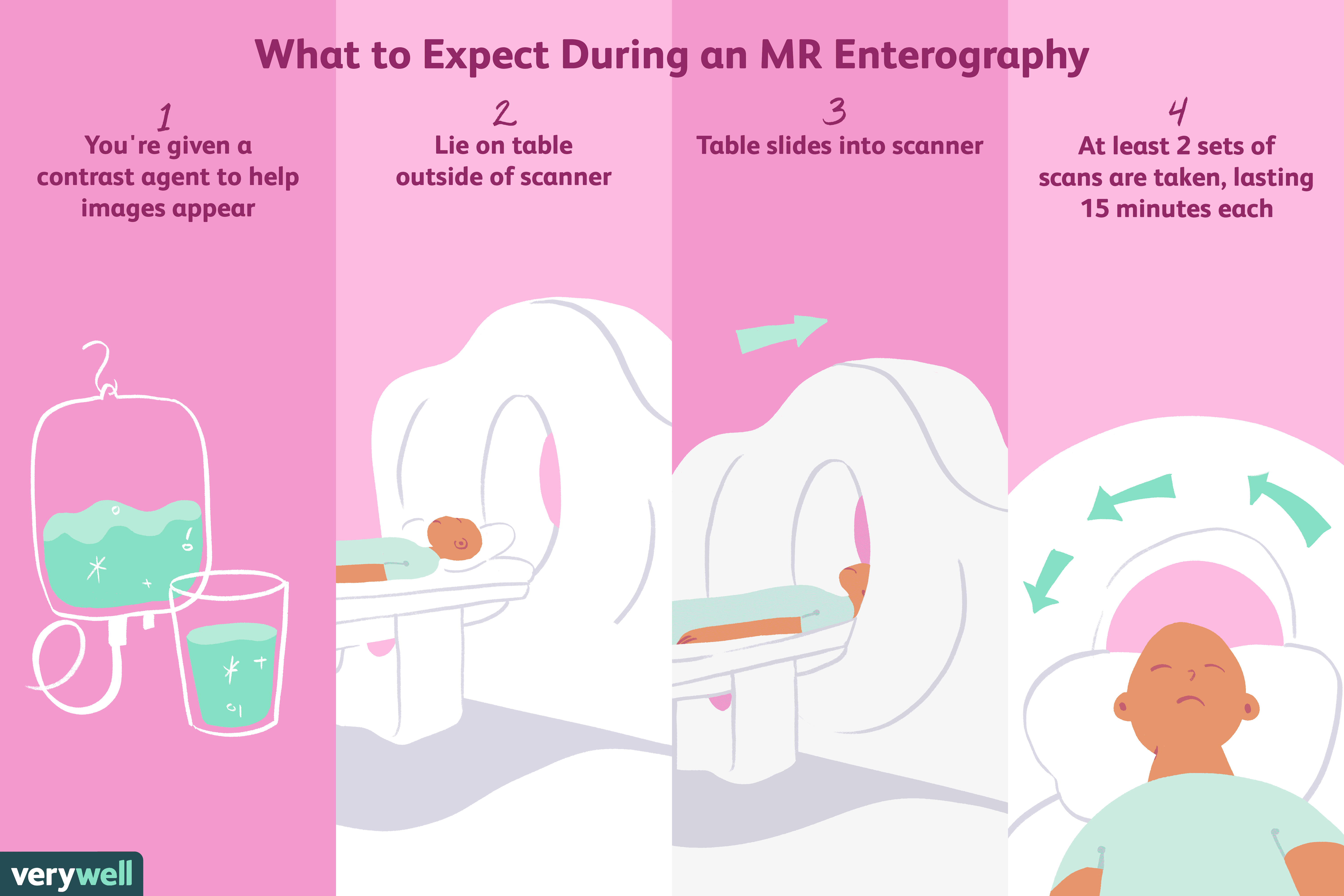

Che cos'è l'enterografia a risonanza magnetica?

Che cos'è l'enterografia a risonanza magnetica?

Disturbi digestivi:guida visiva alle ulcere allo stomaco

Disturbi digestivi:guida visiva alle ulcere allo stomaco

La plastica ora si trova comunemente nelle feci umane

La plastica ora si trova comunemente nelle feci umane

Epatica e crisi alcolica

Il fegato è il tuo organo interno più grande, con un peso di circa 1,5 kg negli adulti. Il tuo fegato si trova appena sotto le costole nella parte superiore destra delladdome. Svolge più di 500 funzio

Epatica e crisi alcolica

Il fegato è il tuo organo interno più grande, con un peso di circa 1,5 kg negli adulti. Il tuo fegato si trova appena sotto le costole nella parte superiore destra delladdome. Svolge più di 500 funzio

Quando dovrei preoccuparmi del dolore da ernia?

Cosè il dolore da ernia? Puoi avere unernia senza provare alcun dolore. È una buona idea chiedere consiglio a un medico se ti ritrovi a provare dolore da ernia insieme ad altri sintomi. Unernia

Quando dovrei preoccuparmi del dolore da ernia?

Cosè il dolore da ernia? Puoi avere unernia senza provare alcun dolore. È una buona idea chiedere consiglio a un medico se ti ritrovi a provare dolore da ernia insieme ad altri sintomi. Unernia

Quali sono i cibi migliori da mangiare quando si ha un'ulcera allo stomaco?

Cosè unulcera allo stomaco? Le ulcere dello stomaco sono ferite aperte che si sviluppano sul rivestimento dello stomaco quando gli acidi del cibo digerito danneggiano la parete dello stomaco. Alime

Quali sono i cibi migliori da mangiare quando si ha un'ulcera allo stomaco?

Cosè unulcera allo stomaco? Le ulcere dello stomaco sono ferite aperte che si sviluppano sul rivestimento dello stomaco quando gli acidi del cibo digerito danneggiano la parete dello stomaco. Alime