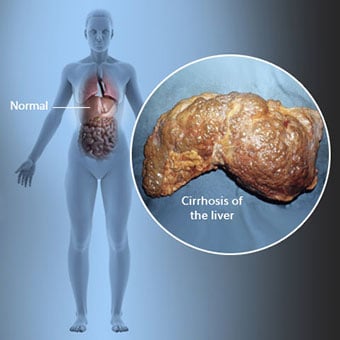

La cirrhose est une complication d'une maladie du foie qui implique une perte de cellules hépatiques et une cicatrisation irréversible du foie.

La cirrhose est une complication d'une maladie du foie qui implique une perte de cellules hépatiques et une cicatrisation irréversible du foie. Les personnes atteintes de cirrhose peuvent avoir peu ou pas de symptômes et de signes de maladie du foie. Certains des symptômes peuvent être non spécifiques, c'est-à-dire qu'ils ne suggèrent pas que le foie en est la cause. Certains des symptômes et signes les plus courants de la cirrhose comprennent :

Les personnes atteintes de cirrhose développent également des symptômes et des signes des complications de la cirrhose.

Il existe de nombreuses causes de cirrhose, notamment des produits chimiques (comme l'alcool, les graisses et certains médicaments), des virus, des les métaux et les maladies auto-immunes du foie dans lesquelles le système immunitaire de l'organisme attaque le foie.

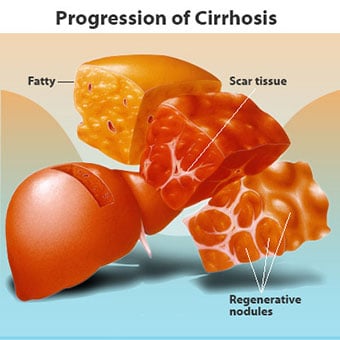

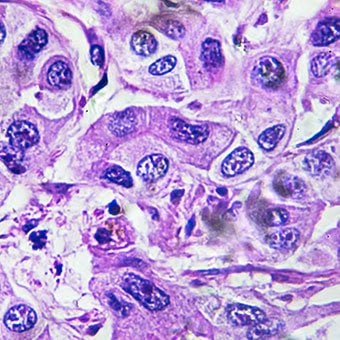

Il existe de nombreuses causes de cirrhose, notamment des produits chimiques (comme l'alcool, les graisses et certains médicaments), des virus, des les métaux et les maladies auto-immunes du foie dans lesquelles le système immunitaire de l'organisme attaque le foie. La cirrhose est une complication de nombreuses maladies du foie caractérisées par une structure et une fonction anormales du foie. Les maladies qui conduisent à la cirrhose le font parce qu'elles endommagent et tuent les cellules hépatiques, après quoi l'inflammation et la réparation associées à la mort des cellules hépatiques provoquent la formation de tissu cicatriciel. Les cellules hépatiques qui ne meurent pas se multiplient pour tenter de remplacer les cellules qui sont mortes. Il en résulte des amas de cellules hépatiques nouvellement formées (nodules régénératifs) dans le tissu cicatriciel. Il existe de nombreuses causes de cirrhose, notamment des produits chimiques (tels que l'alcool, les graisses et certains médicaments), des virus, des métaux toxiques (tels que le fer et le cuivre qui s'accumulent dans le foie à la suite de maladies génétiques) et une maladie hépatique auto-immune dans laquelle le le système immunitaire du corps attaque le foie.

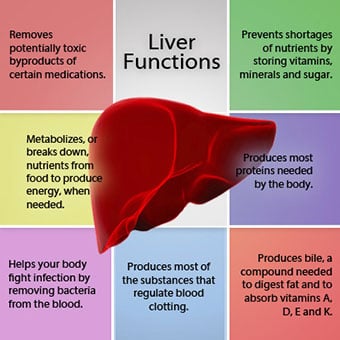

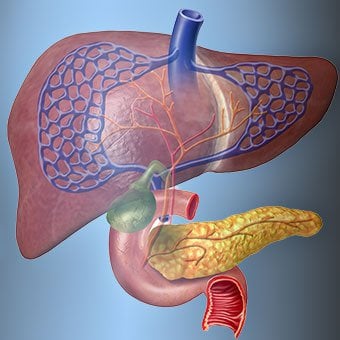

La relation entre le foie et le sang est unique.

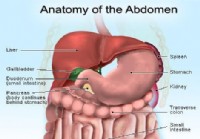

La relation entre le foie et le sang est unique. Le foie est un organe important du corps. Il remplit de nombreuses fonctions essentielles, dont deux produisent des substances nécessaires à l'organisme, par exemple, la coagulation des protéines nécessaires à la coagulation du sang et l'élimination des substances toxiques qui peuvent être nocives pour l'organisme, par exemple, comme les médicaments. . Le foie joue également un rôle important dans la régulation de l'apport de glucose (sucre) et de lipides (graisse) que l'organisme utilise comme carburant. Afin d'accomplir ces fonctions critiques, les cellules hépatiques doivent fonctionner normalement et elles doivent se trouver à proximité du sang, car les substances qui sont ajoutées ou retirées par le foie sont transportées vers et depuis le foie par le sang.

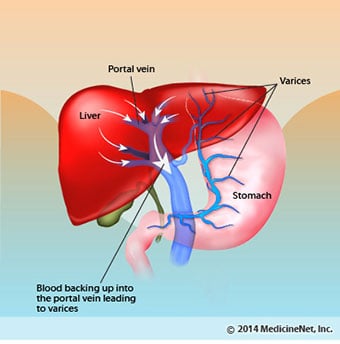

La relation entre le foie et le sang est unique. Contrairement à la plupart des organes du corps, seule une petite quantité de sang est fournie au foie par les artères. La majeure partie de l'approvisionnement en sang du foie provient des veines intestinales lorsque le sang retourne au cœur. La veine principale qui ramène le sang des intestins s'appelle la veine porte. Au fur et à mesure que la veine porte traverse le foie, elle se divise en veines de plus en plus petites. Les plus petites veines (appelées sinusoïdes en raison de leur structure unique) sont en contact étroit avec les cellules du foie. Les cellules hépatiques s'alignent le long des sinusoïdes. Cette relation étroite entre les cellules hépatiques et le sang de la veine porte permet aux cellules hépatiques d'éliminer et d'ajouter des substances au sang. Une fois que le sang a traversé les sinusoïdes, il est collecté dans des veines de plus en plus grosses qui forment finalement une seule veine, la veine hépatique, qui renvoie le sang vers le cœur.

Dans la cirrhose, la relation entre le sang et les cellules hépatiques est détruite. Même si les cellules hépatiques qui survivent ou sont nouvellement formées peuvent être capables de produire et d'éliminer des substances du sang, elles n'ont pas la relation normale et intime avec le sang, ce qui interfère avec la capacité des cellules hépatiques à ajouter ou à éliminer des substances. du sang. De plus, la cicatrisation dans le foie cirrhotique obstrue la circulation du sang dans le foie et vers les cellules hépatiques. En raison de l'obstruction de la circulation du sang dans le foie, le sang "refoule" dans la veine porte et la pression dans la veine porte augmente, une condition appelée hypertension portale. En raison de l'obstruction de l'écoulement et des pressions élevées dans la veine porte, le sang dans la veine porte cherche d'autres veines dans lesquelles retourner vers le cœur, des veines à plus faibles pressions qui contournent le foie. Malheureusement, le foie est incapable d'ajouter ou de retirer des substances du sang qui le contourne. C'est une combinaison de nombre réduit de cellules hépatiques, de perte du contact normal entre le sang traversant le foie et les cellules hépatiques, et de sang contournant le foie qui conduit à de nombreux signes de cirrhose.

Une deuxième raison des problèmes causés par la cirrhose est la relation perturbée entre les cellules du foie et les canaux par lesquels la bile circule. La bile est un liquide produit par les cellules du foie qui a deux fonctions importantes :aider à la digestion et retirer et éliminer les substances toxiques du corps. La bile produite par les cellules hépatiques est sécrétée dans de très petits canaux qui s'étendent entre les cellules hépatiques qui tapissent les sinusoïdes, appelés canalicules. Les canalicules se vident dans de petits conduits qui se rejoignent ensuite pour former des conduits de plus en plus gros. Tous les conduits se combinent en un seul conduit qui pénètre dans l'intestin grêle où il peut aider à la digestion des aliments. Dans le même temps, les substances toxiques contenues dans la bile pénètrent dans l'intestin puis sont éliminées dans les selles. Dans la cirrhose, les canalicules sont anormaux et la relation entre les cellules hépatiques et les canalicules est détruite, tout comme la relation entre les cellules hépatiques et le sang dans les sinusoïdes. En conséquence, le foie n'est pas en mesure d'éliminer normalement les substances toxiques et celles-ci peuvent s'accumuler dans l'organisme. Dans une moindre mesure, la digestion dans l'intestin est également réduite.

Les symptômes et signes courants de la cirrhose comprennent la jaunisse, la fatigue, la faiblesse, la perte d'appétit, les démangeaisons et les ecchymoses.

Les symptômes et signes courants de la cirrhose comprennent la jaunisse, la fatigue, la faiblesse, la perte d'appétit, les démangeaisons et les ecchymoses. Les personnes atteintes de cirrhose peuvent avoir peu ou pas de symptômes et de signes de maladie du foie. Certains des symptômes peuvent être non spécifiques et ne suggèrent pas que le foie en soit la cause. Les symptômes et signes courants de la cirrhose incluent :

Les personnes atteintes de cirrhose Si le foie développent également des symptômes et des signes des complications de la maladie.

La cirrhose en soi est déjà un stade avancé de l'atteinte hépatique. Aux premiers stades de la maladie du foie, il y aura une inflammation du foie. Si cette inflammation n'est pas traitée, elle peut entraîner des cicatrices (fibrose). À ce stade, il est encore possible pour le foie de guérir avec un traitement.

Si la fibrose du foie n'est pas traitée, elle peut entraîner une cirrhose. À ce stade, le tissu cicatriciel ne peut pas guérir, mais la progression de la cicatrisation peut être empêchée ou ralentie. Les personnes atteintes de cirrhose qui présentent des signes de complications peuvent développer une maladie hépatique en phase terminale (ESLD) et le seul traitement à ce stade est la transplantation hépatique.

Œdème, ascite et complications de la péritonite bactérienne

Œdème, ascite et complications de la péritonite bactérienne Lorsque la cirrhose du foie devient grave, des signaux sont envoyés aux reins pour retenir le sel et l'eau dans le corps. L'excès de sel et d'eau s'accumule d'abord dans les tissus sous la peau des chevilles et des jambes sous l'effet de la gravité en position debout ou assise. Cette accumulation de liquide est appelée œdème périphérique ou œdème piquant. (L'œdème piquant fait référence au fait qu'une pression ferme du bout du doigt contre une cheville ou une jambe avec œdème provoque une indentation dans la peau qui persiste pendant un certain temps après le relâchement de la pression. Tout type de pression, comme celle de la bande élastique d'une chaussette , peut suffire à provoquer des piqûres.) Le gonflement est souvent pire à la fin d'une journée après être resté debout ou assis et peut diminuer pendant la nuit en position couchée. À mesure que la cirrhose s'aggrave et que davantage de sel et d'eau sont retenus, du liquide peut également s'accumuler dans la cavité abdominale entre la paroi abdominale et les organes abdominaux (appelé ascite), provoquant un gonflement de l'abdomen, une gêne abdominale et une prise de poids.

Le liquide dans la cavité abdominale (ascite) est l'endroit idéal pour la croissance des bactéries. Normalement, la cavité abdominale contient une très petite quantité de liquide qui peut bien résister à l'infection, et les bactéries qui pénètrent dans l'abdomen (généralement à partir de l'intestin) sont tuées ou trouvent leur chemin dans la veine porte et le foie où elles sont tuées. Dans la cirrhose, le liquide qui s'accumule dans l'abdomen est incapable de résister normalement à l'infection. De plus, davantage de bactéries se frayent un chemin de l'intestin vers l'ascite. Une infection de l'abdomen et de l'ascite, appelée péritonite bactérienne spontanée ou SBP, est susceptible de se produire. La PAS est une complication potentiellement mortelle. Certains patients atteints de PAS ne présentent aucun symptôme, tandis que d'autres ont de la fièvre, des frissons, des douleurs et une sensibilité abdominales, de la diarrhée et une aggravation de l'ascite.

Complications hémorragiques et spléniques

Complications hémorragiques et spléniques Dans le foie cirrhotique, le tissu cicatriciel bloque le flux sanguin retournant vers le cœur depuis les intestins et augmente la pression dans la veine porte (hypertension portale). Lorsque la pression dans la veine porte devient suffisamment élevée, le sang circule dans le foie à travers les veines à faible pression pour atteindre le cœur. Les veines les plus courantes par lesquelles le sang contourne le foie sont les veines tapissant la partie inférieure de l'œsophage et la partie supérieure de l'estomac.

En raison de l'augmentation du flux sanguin et de l'augmentation de pression qui en résulte, les veines du bas de l'œsophage et du haut de l'estomac se dilatent et sont alors appelées varices œsophagiennes et gastriques; plus la pression portale est élevée, plus les varices sont grosses et plus le patient est susceptible de saigner des varices dans l'œsophage ou l'estomac.

Les saignements de varices sont graves et sans traitement immédiat peuvent être mortels. Les symptômes de saignement de varices comprennent des vomissements de sang (il peut apparaître sous forme de sang rouge mélangé à des caillots ou du «marc de café»), des selles noires et goudronneuses en raison de changements dans le sang lors de son passage dans l'intestin (méléna) et des selles orthostatiques étourdissements ou évanouissements (causés par une baisse de la pression artérielle, en particulier lorsque vous vous levez d'une position couchée).

Les saignements peuvent rarement se produire à partir de varices qui se forment ailleurs dans les intestins, par exemple, le côlon. Les patients hospitalisés en raison de varices œsophagiennes hémorragiques actives ont un risque élevé de développer une péritonite bactérienne spontanée, bien que les raisons n'en soient pas encore comprises.

La rate agit normalement comme un filtre pour éliminer les globules rouges, les globules blancs et les plaquettes (petites particules importantes pour la coagulation du sang). Le sang qui s'écoule de la rate rejoint le sang de la veine porte des intestins. À mesure que la pression dans la veine porte augmente dans la cirrhose, elle bloque de plus en plus le flux sanguin de la rate. Le sang "sauvegarde", s'accumule dans la rate, et la rate gonfle, une condition appelée splénomégalie. Parfois, la rate est tellement hypertrophiée qu'elle provoque des douleurs abdominales.

Au fur et à mesure que la rate grossit, elle filtre de plus en plus de cellules sanguines et de plaquettes jusqu'à ce que leur nombre dans le sang diminue. L'hypersplénisme est le terme utilisé pour décrire cette affection, et il est associé à un faible nombre de globules rouges (anémie), à un faible nombre de globules blancs (leucopénie) et/ou à un faible nombre de plaquettes (thrombocytopénie). L'anémie peut entraîner une faiblesse, la leucopénie peut entraîner des infections et la thrombocytopénie peut altérer la coagulation du sang et entraîner des saignements prolongés

Complications hépatiques (hépatiques)

Complications hépatiques (hépatiques) La cirrhose, quelle qu'en soit la cause, augmente le risque de cancer primitif du foie (carcinome hépatocellulaire). Primaire fait référence au fait que la tumeur prend naissance dans le foie. Un cancer du foie secondaire est un cancer qui prend naissance ailleurs dans le corps et se propage (métastase) au foie.

Les symptômes et les signes les plus courants du cancer primitif du foie sont des douleurs et un gonflement abdominaux, une hypertrophie du foie, une perte de poids et de la fièvre. De plus, les cancers du foie peuvent produire et libérer un certain nombre de substances, y compris celles qui provoquent une augmentation du nombre de globules rouges (érythrocytose), une hypoglycémie (hypoglycémie) et une hypercalcémie (hypercalcémie).

Une partie des protéines des aliments qui échappent à la digestion et à l'absorption est utilisée par des bactéries normalement présentes dans l'intestin. En utilisant la protéine à leurs propres fins, les bactéries fabriquent des substances qu'elles libèrent dans l'intestin pour ensuite être absorbées par le corps. Certaines de ces substances, comme l'ammoniac, peuvent avoir des effets toxiques sur le cerveau. Habituellement, ces substances toxiques sont transportées de l'intestin dans la veine porte vers le foie où elles sont retirées du sang et détoxifiées.

Lorsque la cirrhose est présente, les cellules hépatiques ne peuvent pas fonctionner normalement soit parce qu'elles sont endommagées, soit parce qu'elles ont perdu leur relation normale avec le sang. De plus, une partie du sang dans la veine porte contourne le foie par d'autres veines. Le résultat de ces anomalies est que les substances toxiques ne peuvent pas être éliminées par les cellules du foie et s'accumulent plutôt dans le sang.

Lorsque les substances toxiques s'accumulent suffisamment dans le sang, la fonction du cerveau est altérée, une condition appelée encéphalopathie hépatique. Dormir le jour plutôt que la nuit (inversion du rythme normal du sommeil) est un symptôme précoce de l'encéphalopathie hépatique. D'autres symptômes incluent l'irritabilité, l'incapacité à se concentrer ou à effectuer des calculs, la perte de mémoire, la confusion ou des niveaux de conscience déprimés. En fin de compte, une encéphalopathie hépatique sévère provoque le coma et la mort.

Les substances toxiques rendent également le cerveau des patients atteints de cirrhose très sensible aux médicaments normalement filtrés et détoxifiés par le foie. Les doses de nombreux médicaments peuvent devoir être réduites pour éviter une accumulation toxique dans la cirrhose, en particulier les sédatifs et les médicaments utilisés pour favoriser le sommeil. Alternativement, des médicaments peuvent être utilisés qui n'ont pas besoin d'être détoxifiés ou éliminés du corps par le foie, tels que les médicaments éliminés par les reins.

Les patients dont la cirrhose s'aggrave peuvent développer un syndrome hépatorénal. Ce syndrome est une complication grave dans laquelle la fonction des reins est réduite. Il s'agit d'un problème fonctionnel dans les reins, ce qui signifie qu'il n'y a aucun dommage physique aux reins. Au lieu de cela, la fonction réduite est due à des changements dans la façon dont le sang circule dans les reins eux-mêmes. Le syndrome hépatorénal est défini comme une incapacité progressive des reins à éliminer les substances du sang et à produire des quantités adéquates d'urine alors que d'autres fonctions importantes du rein, telles que la rétention de sel, sont maintenues. Si la fonction hépatique s'améliore ou si un foie sain est transplanté chez un patient atteint du syndrome hépatorénal, les reins recommencent généralement à fonctionner normalement. Cela suggère que la fonction réduite des reins est le résultat soit de l'accumulation de substances toxiques dans le sang, soit d'une fonction hépatique anormale lorsque le foie est défaillant. Il existe deux types de syndrome hépatorénal. Un type se produit progressivement au fil des mois. L'autre survient rapidement sur une semaine ou deux.

Rarement, certains patients atteints de cirrhose avancée peuvent développer un syndrome hépatopulmonaire. Ces patients peuvent éprouver des difficultés à respirer parce que certaines hormones libérées lors d'une cirrhose avancée entraînent un fonctionnement anormal des poumons. Le problème fondamental dans les poumons est qu'il n'y a pas assez de sang qui circule dans les petits vaisseaux sanguins des poumons qui sont en contact avec les alvéoles (sacs aériens) des poumons. Le sang circulant dans les poumons est shunté autour des alvéoles et ne peut pas capter suffisamment d'oxygène de l'air dans les alvéoles. En conséquence, le patient éprouve un essoufflement, en particulier à l'effort.

Il existe 12 causes courantes de cirrhose.

Il existe 12 causes courantes de cirrhose. Common causes of cirrhosis of the liver include:

Less common causes of cirrhosis include:

In certain parts of the world (particularly Northern Africa), infection of the liver with a parasite (schistosomiasis) is the most common cause of liver disease and cirrhosis.

Alcohol and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease are common causes of cirrhosis.

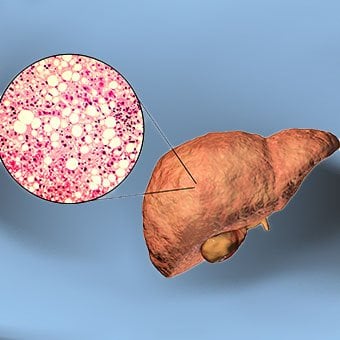

Alcohol and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease are common causes of cirrhosis. Alcohol is a very common cause of cirrhosis, particularly in the Western world. Chronic, high levels of alcohol consumption injure liver cells. Thirty percent of individuals who drink daily at least eight to sixteen ounces of hard liquor or the equivalent for fifteen or more years will develop cirrhosis. Alcohol causes a range of liver diseases, which include simple and uncomplicated fatty liver (steatosis), more serious fatty liver with inflammation (steatohepatitis or alcoholic hepatitis), and cirrhosis.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) refers to a wide spectrum of liver diseases that, like alcoholic liver disease, range from simple steatosis, to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), to cirrhosis. All stages of NAFLD have in common the accumulation of fat in liver cells. The term nonalcoholic is used because NAFLD occurs in individuals who do not consume excessive amounts of alcohol, yet in many respects the microscopic picture of NAFLD is similar to what can be seen in liver disease that is due to excessive alcohol. NAFLD is associated with a condition called insulin resistance, which, in turn, is associated with metabolic syndrome and diabetes mellitus type 2. Obesity is the main cause of insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes. NAFLD is the most common liver disease in the United States and is responsible for up to 25% of all liver disease. The number of livers transplanted for NAFLD-related cirrhosis is on the rise. Public health officials are worried that the current epidemic of obesity will dramatically increase the development of NAFLD and cirrhosis in the population.

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a liver disease caused by an abnormality of the immune system that is found predominantly in women.

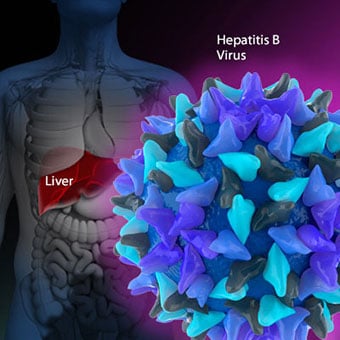

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a liver disease caused by an abnormality of the immune system that is found predominantly in women. Chronic viral hepatitis is a condition in which hepatitis B or hepatitis C virus infects the liver for years. Most patients with viral hepatitis will not develop chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis. The majority of patients infected with hepatitis A recover completely within weeks, without developing chronic infection. In contrast, some patients infected with hepatitis B virus and most patients infected with hepatitis C virus develop chronic hepatitis, which, in turn, causes progressive liver damage and leads to cirrhosis, and, sometimes, liver cancers.

Autoimmune hepatitis is a liver disease found more commonly in women that is caused by an abnormality of the immune system. The abnormal immune activity in autoimmune hepatitis causes progressive inflammation and destruction of liver cells (hepatocytes), leading ultimately to cirrhosis.

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a liver disease caused by an abnormality of the immune system that is found predominantly in women. The abnormal immunity in PBC causes chronic inflammation and destruction of the small bile ducts within the liver. The bile ducts are passages within the liver through which bile travels to the intestine. Bile is a fluid produced by the liver that contains substances required for digestion and absorption of fat in the intestine, as well as other compounds that are waste products, such as the pigment bilirubin. (Bilirubin is produced by the breakdown of hemoglobin from old red blood cells.). Along with the gallbladder, the bile ducts make up the biliary tract. In PBC, the destruction of the small bile ducts blocks the normal flow of bile into the intestine. As the inflammation continues to destroy more of the bile ducts, it also spreads to destroy nearby liver cells. As the destruction of the hepatocytes proceeds, scar tissue (fibrosis) forms and spreads throughout the areas of destruction. The combined effects of progressive inflammation, scarring, and the toxic effects of accumulating waste products culminates in cirrhosis.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is an uncommon disease frequently found in patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. In PSC, the large bile ducts outside of the liver become inflamed, narrowed, and obstructed. Obstruction to the flow of bile leads to infections of the bile ducts and jaundice, eventually causing cirrhosis. In some patients, injury to the bile ducts (usually because of surgery) also can cause obstruction and cirrhosis of the liver.

Different liver diseases should be diagnosed by specialists and different tests such as liver blood test, biopsy, and others.

Different liver diseases should be diagnosed by specialists and different tests such as liver blood test, biopsy, and others. Inherited (genetic) disorders that result in the accumulation of toxic substances in the liver, which leads to tissue damage and cirrhosis. Examples include the abnormal accumulation of iron (hemochromatosis) or copper (Wilson disease). In hemochromatosis, patients inherit a tendency to absorb an excessive amount of iron from food. Over time, iron accumulation in different organs throughout the body causes cirrhosis, arthritis, heart muscle damage leading to heart failure, and testicular dysfunction causing loss of sexual drive. Treatment is aimed at preventing damage to organs by removing iron from the body through phlebotomy (removing blood). In Wilson disease, there is an inherited abnormality in one of the proteins that control copper in the body. Over time, copper accumulates in the liver, eyes, and brain. Cirrhosis, tremor, psychiatric disturbances, and other neurological difficulties occur if the condition is not treated early. Treatment is with oral medication, which increases the amount of copper that is eliminated from the body in the urine.

Cryptogenic cirrhosis (cirrhosis due to unidentified causes) is a common reason for liver transplantation. It is termed called cryptogenic cirrhosis because for many years doctors have been being unable to explain why a proportion of patients developed cirrhosis. Doctors now believe that cryptogenic cirrhosis is due to NASH (nonalcoholic steatohepatitis) caused by long-standing obesity, type 2 diabetes, and insulin resistance. The fat in the liver of patients with NASH is believed to disappear with the onset of cirrhosis, and this has made it difficult for doctors to make the connection between NASH and cryptogenic cirrhosis for a long time. One important clue that NASH leads to cryptogenic cirrhosis is the finding of a high occurrence of NASH in the new livers of patients undergoing liver transplant for cryptogenic cirrhosis. Finally, a study from France suggests that patients with NASH have a similar risk of developing cirrhosis as patients with long-standing infection with hepatitis C virus. (See discussion that follows.) However, the progression to cirrhosis from NASH is thought to be slow and the diagnosis of cirrhosis typically is made in people in their sixties.

Infants can be born without bile ducts (biliary atresia) and ultimately develop cirrhosis. Other infants are born lacking vital enzymes for controlling sugars that lead to the accumulation of sugars and cirrhosis. On rare occasions, the absence of a specific enzyme can cause cirrhosis and scarring of the lung (alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency).

Less common causes of cirrhosis include unusual reactions to some drugs and prolonged exposure to toxins, as well as chronic heart failure (cardiac cirrhosis). In certain parts of the world (particularly Northern Africa), infection of the liver with a parasite (schistosomiasis) is the most common cause of liver disease and cirrhosis.

Different liver diseases should be diagnosed by specialists and different tests such as liver blood test, biopsy, and others.

Different liver diseases should be diagnosed by specialists and different tests such as liver blood test, biopsy, and others. The single best test for diagnosing cirrhosis is a biopsy of the liver. Liver biopsies carry a small risk for serious complications, and biopsy often is reserved for those patients in whom the diagnosis of the type of liver disease or the presence of cirrhosis is not clear. The history, physical examination, or routine testing may suggest the possibility of cirrhosis. If cirrhosis is present, other tests can be used to determine the severity of the cirrhosis and the presence of complications. Tests also may be used to diagnose the underlying disease that is causing the cirrhosis. Examples of how doctors diagnose and evaluate cirrhosis are:

There are four types of treatment of cirrhosis.

There are four types of treatment of cirrhosis. Treatment of cirrhosis includes

Consume a balanced diet and one multivitamin daily. Patients with PBC with impaired absorption of fat-soluble vitamins may need additional vitamins D and K.

Avoid drugs (including alcohol) that cause liver damage. All patients with cirrhosis should avoid alcohol. Most patients with alcohol-induced cirrhosis experience an improvement in liver function with abstinence from alcohol. Even patients with chronic hepatitis B and C can substantially reduce liver damage and slow the progression towards cirrhosis with abstinence from alcohol.

Avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, e.g., ibuprofen). Patients with cirrhosis can experience worsening of liver and kidney function with NSAIDs.

Eradicate hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus by using anti-viral medications. Not all patients with cirrhosis due to chronic viral hepatitis are candidates for drug treatment. Some patients may experience serious deterioration in liver function and/or intolerable side effects during treatment. Thus, decisions to treat viral hepatitis have to be individualized, after consulting with doctors experienced in treating liver diseases (hepatologists).

Remove blood from patients with hemochromatosis to reduce the levels of iron and prevent further damage to the liver. In Wilson's disease, medications can be used to increase the excretion of copper in the urine to reduce the levels of copper in the body and prevent further damage to the liver.

Suppress the immune system with drugs such as prednisone and azathioprine (Imuran) to decrease inflammation of the liver in autoimmune hepatitis.

Treat patients with PBC with a bile acid preparation, ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), also called ursodiol (Actigall). Results of an analysis that combined the results from several clinical trials showed that UDCA increased survival among PBC patients during 4 years of therapy. The development of portal hypertension also was reduced by the UDCA. It is important to note that despite producing clear benefits, UDCA treatment primarily retards progression and does not cure PBC. Other medications such as colchicine and methotrexate also may have benefits in subsets of patients with PBC.

Immunize patients with cirrhosis against infection with hepatitis A and B to prevent a serious deterioration in liver. There are currently no vaccines available for immunizing against hepatitis C.

Treatment for edema, ascites, and hypersplenism complications.

Treatment for edema, ascites, and hypersplenism complications. Retaining salt and water can lead to swelling of the ankles and legs (edema) or abdomen (ascites) in patients with cirrhosis. Doctors often advise patients with cirrhosis to restrict dietary salt (sodium) and fluid to decrease edema and ascites. The amount of salt in the diet usually is restricted to 2 grams per day and fluid to 1.2 liters per day. In most patients with cirrhosis, salt and fluid restriction is not enough and diuretics have to be added.

Diuretics are medications that work in the kidneys to promote the elimination of salt and water into the urine. A combination of the diuretics spironolactone (Aldactone) and furosemide (Lasix) can reduce or eliminate the edema and ascites in most patients. During treatment with diuretics, it is important to monitor the function of the kidneys by measuring blood levels of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine to determine if too much diuretic is being used. Too much diuretic can lead to kidney dysfunction that is reflected in elevations of the BUN and creatinine levels in the blood.

Sometimes, when the diuretics do not work (in which case the ascites is said to be refractory), a long needle or catheter is used to draw out the ascitic fluid directly from the abdomen, a procedure called abdominal paracentesis. It is common to withdraw large amounts (liters) of fluid from the abdomen when the ascites is causing painful abdominal distension and/or difficulty breathing because it limits the movement of the diaphragms.

Another treatment for refractory ascites is a procedure called transjugular intravenous portosystemic shunting (TIPS).

The spleen normally acts as a filter to remove older red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets (small particles important for the clotting of blood). The blood that drains from the spleen joins the blood in the portal vein from the intestines. As the pressure in the portal vein rises in cirrhosis, it increasingly blocks the flow of blood from the spleen. The blood "backs-up," accumulating in the spleen, and the spleen swells in size, a condition referred to as splenomegaly. Sometimes, the spleen is so enlarged it causes abdominal pain.

As the spleen enlarges, it filters out more and more of the blood cells and platelets until their numbers in the blood are reduced. Hypersplenism is the term used to describe this condition, and it is associated with a low red blood cell count (anemia), low white blood cell count (leukopenia), and/or a low platelet count (thrombocytopenia). Anemia can cause weakness, leucopenia can lead to infections, and thrombocytopenia can impair the clotting of blood and result in prolonged bleeding.

Once varices have bled, they tend to rebleed and the probability that a patient will die from each bleeding episode is high (30% to 35%). Treatment is necessary to prevent the first bleeding episode as well as rebleeding.

Once varices have bled, they tend to rebleed and the probability that a patient will die from each bleeding episode is high (30% to 35%). Treatment is necessary to prevent the first bleeding episode as well as rebleeding. If large varices develop in the esophagus or upper stomach, patients with cirrhosis are at risk for serious bleeding due to rupture of these varices. Once varices have bled, they tend to rebleed and the probability that a patient will die from each bleeding episode is high (30% to 35%). Treatment is necessary to prevent the first bleeding episode as well as rebleeding. Treatments include medications and procedures to decrease the pressure in the portal vein and procedures to destroy the varices.

Hepatic encephalopathy usually should be treated with a low protein diet and oral lactulose.

Hepatic encephalopathy usually should be treated with a low protein diet and oral lactulose. Patients with an abnormal sleep cycle, impaired thinking, odd behavior, or other signs of hepatic encephalopathy usually should be treated with a low protein diet and oral lactulose. Dietary protein is restricted because it is a source of toxic compounds that cause hepatic encephalopathy. Lactulose, which is a liquid, traps toxic compounds in the colon so they cannot be absorbed into the bloodstream, and thus cause encephalopathy. Lactulose is converted to lactic acid in the colon, and the acidic environment that results is believed to trap the toxic compounds produced by the bacteria. To be sure adequate lactulose is present in the colon at all times, the patient should adjust the dose to produce 2 to 3 semiformed bowel movements a day. Lactulose is a laxative, and the effectiveness of treatment can be judged by loosening or increasing the frequency of stools. Rifaximin (Xifaxan) is an antibiotic taken orally that is not absorbed into the body but rather remains in the intestines. It is the preferred mode of treatment of hepatic encephalopathy. Antibiotics work by suppressing the bacteria that produce the toxic compounds in the colon.

Most patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis are hospitalized and treated with intravenous antibiotics.

Most patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis are hospitalized and treated with intravenous antibiotics. Patients suspected of having spontaneous bacterial peritonitis usually will undergo paracentesis. The fluid that is removed is examined for white blood cells and cultured for bacteria. Culturing involves inoculating a sample of the ascites into a bottle of nutrient-rich fluid that encourages the growth of bacteria, thus facilitating the identification of even small numbers of bacteria. Blood and urine samples also are often obtained for culturing because many patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis also will have infections in their blood and urine. Many doctors believe the infection may have begun in the blood and the urine and spread to the ascitic fluid to cause spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Most patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis are hospitalized and treated with intravenous antibiotics such as cefotaxime (Claforan). Patients usually treated with antibiotics include:

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is a serious infection. It often occurs in patients with advanced cirrhosis whose immune systems are weak, but with modern antibiotics and early detection and treatment, the prognosis of recovering from an episode of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is good.

In some patients, oral antibiotics (norfloxacin [Noroxin] or sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim [Bactrim]) can be prescribed to prevent spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Not all patients with cirrhosis and ascites should be treated with antibiotics to prevent spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, but some patients are at high risk for developing spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and warrant preventive treatment.

The prognosis and life expectancy for cirrhosis of the liver varies and depends on the cause, the severity, any complications, and any underlying diseases.

The prognosis and life expectancy for cirrhosis of the liver varies and depends on the cause, the severity, any complications, and any underlying diseases. Several types of liver disease that cause cirrhosis (such as hepatitis B and C) are associated with a high incidence of liver cancer. It is useful to screen for liver cancer in patients with cirrhosis, as early surgical treatment or transplantation of the liver can cure the patient of cancer. The difficulty is that the methods available for screening are only partially effective, identifying at best only half of patients at a curable stage of their cancer. Despite the partial effectiveness of screening, most patients with cirrhosis, particularly hepatitis B and C, are screened yearly or every six months with ultrasound examination of the liver and measurements of cancer-produced proteins in the blood, for example, alpha-fetoprotein.

Cirrhosis is irreversible. Liver function usually gradually worsens despite treatment, and complications of cirrhosis increase and become difficult to treat. When cirrhosis is far advanced liver transplantation often is the only option for treatment. Recent advances in surgical transplantation and medications to prevent infection and rejection of the transplanted liver have greatly improved survival after transplantation. On average, more than 80% of patients who receive transplants are alive after five years. Not everyone with cirrhosis is a candidate for transplantation. Furthermore, there is a shortage of livers to transplant, and they're usually is a long (months to years) wait before a liver for transplanting becomes available. Measures to slow the progression of liver disease, and treat and prevent complications of cirrhosis are vitally important.

The prognosis and life expectancy for cirrhosis of the liver varies and depends on the cause, the severity, any complications, and any underlying diseases.

Progress in the management and prevention of cirrhosis continues. Research is ongoing to determine the mechanism of scar formation in the liver and how this process of scarring can be interrupted or even reversed. Newer and better treatments for viral liver disease are being developed to prevent the progression to cirrhosis. Prevention of viral hepatitis by vaccination, which is available for hepatitis B, is being developed for hepatitis C. Treatments for the complications of cirrhosis are being developed or revised, and tested continually. Finally, research is being directed at identifying new proteins in the blood that can detect liver cancer early or predict which patients will develop liver cancer.

Comment soutenir quelqu'un qui suit un régime pauvre en FODMAP

Le régime pauvre en FODMAP, ou vraiment tout régime médicalement nécessaire, peut être vraiment isolant. Cela peut vous faire sentir seul, incompris et un inconvénient majeur. Pendant que vous êtes o

Comment soutenir quelqu'un qui suit un régime pauvre en FODMAP

Le régime pauvre en FODMAP, ou vraiment tout régime médicalement nécessaire, peut être vraiment isolant. Cela peut vous faire sentir seul, incompris et un inconvénient majeur. Pendant que vous êtes o

La nutrition personnalisée a encore du chemin à parcourir

Lorsque nous sommes confrontés à la question de savoir quel régime est le meilleur pour notre santé personnelle, la réponse nest pas facile. La réponse individuelle aux interventions diététiques varie

La nutrition personnalisée a encore du chemin à parcourir

Lorsque nous sommes confrontés à la question de savoir quel régime est le meilleur pour notre santé personnelle, la réponse nest pas facile. La réponse individuelle aux interventions diététiques varie

Syndrome du côlon irritable chez l'enfant (IBS chez l'enfant)

Centre du syndrome du côlon irritable chez lenfant (IBS in Children) Images du diaporama sur le syndrome du côlon irritable (IBS) Mythes sur les maladies digestives Quiz sur le syndrome du côlon irrit

Syndrome du côlon irritable chez l'enfant (IBS chez l'enfant)

Centre du syndrome du côlon irritable chez lenfant (IBS in Children) Images du diaporama sur le syndrome du côlon irritable (IBS) Mythes sur les maladies digestives Quiz sur le syndrome du côlon irrit