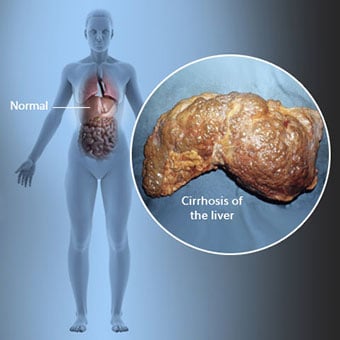

Zirrhose ist eine Komplikation einer Lebererkrankung, die mit dem Verlust von Leberzellen und irreversibler Vernarbung der Leber einhergeht.

Zirrhose ist eine Komplikation einer Lebererkrankung, die mit dem Verlust von Leberzellen und irreversibler Vernarbung der Leber einhergeht. Personen mit Zirrhose können wenige oder keine Symptome und Anzeichen einer Lebererkrankung haben. Einige der Symptome können unspezifisch sein, das heißt, sie deuten nicht darauf hin, dass die Leber ihre Ursache ist. Zu den häufigeren Symptomen und Anzeichen einer Zirrhose gehören:

Personen mit Zirrhose entwickeln auch Symptome und Anzeichen von Komplikationen der Zirrhose.

Es gibt viele Ursachen für Zirrhose, darunter Chemikalien (wie Alkohol, Fett und bestimmte Medikamente), Viren und Giftstoffe Metalle und Autoimmunerkrankungen der Leber, bei denen das körpereigene Immunsystem die Leber angreift.

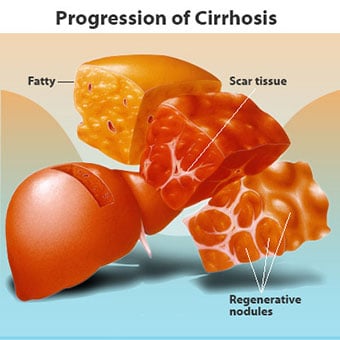

Es gibt viele Ursachen für Zirrhose, darunter Chemikalien (wie Alkohol, Fett und bestimmte Medikamente), Viren und Giftstoffe Metalle und Autoimmunerkrankungen der Leber, bei denen das körpereigene Immunsystem die Leber angreift. Zirrhose ist eine Komplikation vieler Lebererkrankungen, die durch eine abnormale Struktur und Funktion der Leber gekennzeichnet ist. Die Krankheiten, die zu Zirrhose führen, tun dies, weil sie Leberzellen verletzen und töten, woraufhin die Entzündung und Reparatur, die mit den sterbenden Leberzellen verbunden ist, zur Bildung von Narbengewebe führt. Die nicht absterbenden Leberzellen vermehren sich, um die abgestorbenen Zellen zu ersetzen. Dies führt zu Clustern von neu gebildeten Leberzellen (regenerative Knötchen) innerhalb des Narbengewebes. Es gibt viele Ursachen für Zirrhose, darunter Chemikalien (wie Alkohol, Fett und bestimmte Medikamente), Viren, toxische Metalle (wie Eisen und Kupfer, die sich als Folge genetischer Erkrankungen in der Leber ansammeln) und Autoimmunerkrankungen der Leber, bei denen die das körpereigene Immunsystem greift die Leber an.

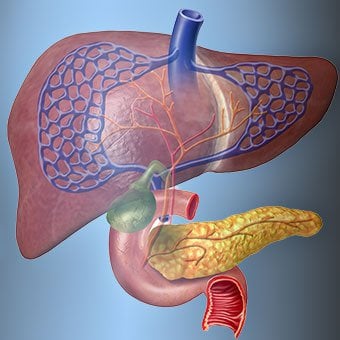

Die Beziehung der Leber zum Blut ist einzigartig.

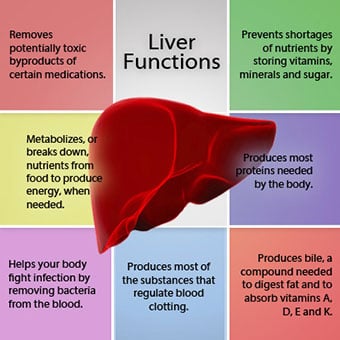

Die Beziehung der Leber zum Blut ist einzigartig. Die Leber ist ein wichtiges Organ im Körper. Es erfüllt viele wichtige Funktionen, von denen zwei vom Körper benötigte Substanzen produzieren, z. B. Proteine gerinnen, die für die Blutgerinnung erforderlich sind, und toxische Substanzen entfernen, die für den Körper schädlich sein können, z. B. Medikamente . Die Leber spielt auch eine wichtige Rolle bei der Regulierung der Zufuhr von Glukose (Zucker) und Lipiden (Fett), die der Körper als Brennstoff verwendet. Um diese kritischen Funktionen ausführen zu können, müssen die Leberzellen normal funktionieren und sich in unmittelbarer Nähe zum Blut befinden, da die Substanzen, die von der Leber hinzugefügt oder entfernt werden, vom Blut zur und von der Leber transportiert werden.

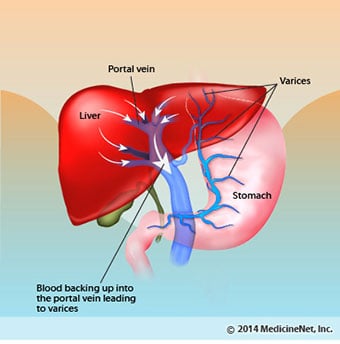

Die Beziehung der Leber zum Blut ist einzigartig. Im Gegensatz zu den meisten Organen im Körper wird die Leber nur in geringem Maße durch Arterien mit Blut versorgt. Der größte Teil der Blutversorgung der Leber erfolgt aus den Darmvenen, wenn das Blut zum Herzen zurückkehrt. Die Hauptvene, die das Blut aus dem Darm zurückführt, wird Pfortader genannt. Wenn die Pfortader durch die Leber verläuft, zerfällt sie in immer kleinere Venen. Die kleinsten Venen (aufgrund ihrer einzigartigen Struktur Sinusoide genannt) stehen in engem Kontakt mit den Leberzellen. Leberzellen reihen sich entlang der Sinusoide aneinander. Diese enge Beziehung zwischen den Leberzellen und dem Blut aus der Pfortader ermöglicht es den Leberzellen, dem Blut Substanzen zu entnehmen und hinzuzufügen. Sobald das Blut die Sinusoide passiert hat, wird es in immer größeren Venen gesammelt, die schließlich eine einzige Vene bilden, die Lebervene, die das Blut zum Herzen zurückführt.

Bei einer Zirrhose ist die Beziehung zwischen Blut und Leberzellen zerstört. Obwohl die überlebenden oder neu gebildeten Leberzellen in der Lage sein können, Substanzen aus dem Blut zu produzieren und zu entfernen, haben sie nicht die normale, enge Beziehung zum Blut, und dies beeinträchtigt die Fähigkeit der Leberzellen, Substanzen hinzuzufügen oder zu entfernen aus dem Blut. Außerdem behindert die Narbenbildung innerhalb der Leberzirrhose den Blutfluss durch die Leber und zu den Leberzellen. Als Folge der Behinderung des Blutflusses durch die Leber staut sich das Blut in der Pfortader und der Druck in der Pfortader steigt an, ein Zustand, der als portale Hypertension bezeichnet wird. Aufgrund der Flussbehinderung und des hohen Drucks in der Pfortader sucht sich das Blut in der Pfortader andere Venen, um zum Herzen zurückzukehren, Venen mit niedrigerem Druck, die die Leber umgehen. Leider ist die Leber nicht in der Lage, Substanzen aus dem Blut hinzuzufügen oder zu entfernen, die sie umgehen. Es ist eine Kombination aus reduzierter Anzahl von Leberzellen, Verlust des normalen Kontakts zwischen Blut, das durch die Leber fließt, und den Leberzellen und Blut, das die Leber umgeht, was zu vielen Anzeichen einer Zirrhose führt.

Ein zweiter Grund für die durch Zirrhose verursachten Probleme ist die gestörte Beziehung zwischen den Leberzellen und den Kanälen, durch die die Galle fließt. Galle ist eine Flüssigkeit, die von Leberzellen produziert wird und zwei wichtige Funktionen hat:die Verdauung zu unterstützen und giftige Substanzen aus dem Körper zu entfernen und zu beseitigen. Die von Leberzellen produzierte Galle wird in sehr kleine Kanäle abgesondert, die zwischen den Leberzellen verlaufen, die die Sinusoide auskleiden, die Canaliculi genannt werden. Die Kanälchen münden in kleine Gänge, die sich dann zu immer größeren Gängen zusammenschließen. Alle Gänge vereinen sich zu einem Gang, der in den Dünndarm eintritt, wo er bei der Verdauung von Nahrung helfen kann. Gleichzeitig gelangen in der Galle enthaltene Giftstoffe in den Darm und werden dann mit dem Stuhl ausgeschieden. Bei Zirrhose sind die Kanälchen abnormal und die Beziehung zwischen Leberzellen und Kanälchen ist zerstört, genau wie die Beziehung zwischen den Leberzellen und dem Blut in den Sinusoiden. Infolgedessen kann die Leber Giftstoffe nicht normal ausscheiden und sie können sich im Körper ansammeln. In geringem Umfang wird auch die Verdauung im Darm reduziert.

Häufige Symptome und Anzeichen einer Zirrhose sind Gelbsucht, Müdigkeit, Schwäche, Appetitlosigkeit, Juckreiz und leichte Blutergüsse.

Häufige Symptome und Anzeichen einer Zirrhose sind Gelbsucht, Müdigkeit, Schwäche, Appetitlosigkeit, Juckreiz und leichte Blutergüsse. Menschen mit Zirrhose können wenige oder keine Symptome und Anzeichen einer Lebererkrankung haben. Einige der Symptome können unspezifisch sein und deuten nicht darauf hin, dass die Leber ihre Ursache ist. Häufige Symptome und Anzeichen einer Zirrhose sind:

Menschen mit Leberzirrhose entwickeln auch Symptome und Anzeichen von Komplikationen der Krankheit.

Zirrhose an sich ist bereits ein Spätstadium einer Leberschädigung. In den frühen Stadien der Lebererkrankung kommt es zu einer Leberentzündung. Wenn diese Entzündung nicht behandelt wird, kann sie zu Narbenbildung (Fibrose) führen. In diesem Stadium ist es noch möglich, dass die Leber mit einer Behandlung heilt.

Wenn die Leberfibrose nicht behandelt wird, kann sie zu einer Zirrhose führen. In diesem Stadium kann das Narbengewebe nicht heilen, aber das Fortschreiten der Narbenbildung kann verhindert oder verlangsamt werden. Menschen mit Zirrhose, die Anzeichen von Komplikationen aufweisen, können eine Lebererkrankung im Endstadium (ESLD) entwickeln, und die einzige Behandlung in diesem Stadium ist eine Lebertransplantation.

Ödeme, Aszites und bakterielle Peritonitis-Komplikationen

Ödeme, Aszites und bakterielle Peritonitis-Komplikationen Wenn die Leberzirrhose schwerwiegend wird, werden Signale an die Nieren gesendet, um Salz und Wasser im Körper zu halten. Das überschüssige Salz und Wasser sammelt sich durch die Wirkung der Schwerkraft beim Stehen oder Sitzen zunächst im Gewebe unter der Haut der Knöchel und Beine an. Diese Flüssigkeitsansammlung wird als peripheres Ödem oder Pitting-Ödem bezeichnet. (Pitting-Ödem bezieht sich auf die Tatsache, dass das feste Drücken einer Fingerspitze gegen einen Knöchel oder ein Bein mit Ödem eine Vertiefung in der Haut verursacht, die einige Zeit nach dem Ablassen des Drucks bestehen bleibt. Jede Art von Druck, z. B. durch das Gummiband einer Socke , kann ausreichen, um Lochfraß zu verursachen.) Die Schwellung ist oft am Ende eines Tages nach dem Stehen oder Sitzen schlimmer und kann im Liegen über Nacht nachlassen. Wenn sich die Zirrhose verschlimmert und mehr Salz und Wasser zurückgehalten werden, kann sich auch Flüssigkeit in der Bauchhöhle zwischen der Bauchwand und den Bauchorganen ansammeln (sogenannter Aszites), was zu Schwellungen des Bauches, Bauchbeschwerden und Gewichtszunahme führt.

Flüssigkeit in der Bauchhöhle (Aszites) ist der perfekte Ort für Bakterien. Normalerweise enthält die Bauchhöhle eine sehr kleine Menge Flüssigkeit, die einer Infektion gut widerstehen kann, und Bakterien, die in den Bauchraum (normalerweise aus dem Darm) gelangen, werden abgetötet oder gelangen in die Pfortader und zur Leber, wo sie abgetötet werden. Bei Zirrhose kann die Flüssigkeit, die sich im Bauchraum ansammelt, einer Infektion nicht normal widerstehen. Außerdem gelangen mehr Bakterien aus dem Darm in den Aszites. Es ist wahrscheinlich, dass eine Infektion innerhalb des Abdomens und des Aszites auftritt, die als spontane bakterielle Peritonitis oder SBP bezeichnet wird. SBP ist eine lebensbedrohliche Komplikation. Einige Patienten mit SBP haben keine Symptome, während andere Fieber, Schüttelfrost, Bauchschmerzen und -empfindlichkeit, Durchfall und sich verschlechternden Aszites haben.

Blutungen und Milzkomplikationen

Blutungen und Milzkomplikationen In der Leberzirrhose blockiert das Narbengewebe den Rückfluss des Blutes aus dem Darm zum Herzen und erhöht den Druck in der Pfortader (portale Hypertonie). Wenn der Druck in der Pfortader hoch genug wird, fließt das Blut durch Venen mit niedrigerem Druck um die Leber herum, um das Herz zu erreichen. Die häufigsten Venen, durch die das Blut die Leber umgeht, sind die Venen, die den unteren Teil der Speiseröhre und den oberen Teil des Magens auskleiden.

Durch den erhöhten Blutfluss und den daraus resultierenden Druckanstieg erweitern sich die Venen in der unteren Speiseröhre und im oberen Magen und werden dann als Ösophagus- und Magenvarizen bezeichnet; Je höher der Pfortaderdruck, desto größer die Varizen und desto wahrscheinlicher ist es, dass ein Patient aus den Varizen in die Speiseröhre oder den Magen blutet.

Blutungen aus Varizen sind schwerwiegend und können ohne sofortige Behandlung tödlich sein. Zu den Symptomen einer Varizenblutung gehören Erbrechen von Blut (es kann als rotes Blut erscheinen, das mit Gerinnseln oder „Kaffeesatz“ vermischt ist), Stuhlgang, der aufgrund von Veränderungen im Blut beim Passieren des Darms (Meläna) schwarz und teerig ist, und orthostatischer Stuhl Schwindel oder Ohnmacht (verursacht durch einen Blutdruckabfall, insbesondere beim Aufstehen aus einer liegenden Position).

Blutungen können selten aus Varizen auftreten, die sich an anderer Stelle im Darm bilden, zum Beispiel im Dickdarm. Patienten, die wegen aktiv blutender Ösophagusvarizen ins Krankenhaus eingeliefert werden, haben ein hohes Risiko, eine spontane bakterielle Peritonitis zu entwickeln, obwohl die Gründe dafür noch nicht geklärt sind.

Die Milz fungiert normalerweise als Filter, um ältere rote Blutkörperchen, weiße Blutkörperchen und Blutplättchen (kleine Partikel, die für die Blutgerinnung wichtig sind) zu entfernen. Das Blut, das aus der Milz abfließt, verbindet sich mit dem Blut in der Pfortader aus dem Darm. Da der Druck in der Pfortader bei Zirrhose ansteigt, blockiert sie zunehmend den Blutfluss aus der Milz. Das Blut „staut“ sich in der Milz und die Milz schwillt an, ein Zustand, der als Splenomegalie bezeichnet wird. Manchmal ist die Milz so vergrößert, dass sie Bauchschmerzen verursacht.

Wenn sich die Milz vergrößert, filtert sie immer mehr Blutzellen und Blutplättchen heraus, bis ihre Anzahl im Blut abnimmt. Hypersplenismus ist der Begriff, der verwendet wird, um diesen Zustand zu beschreiben, und er ist mit einer niedrigen Anzahl roter Blutkörperchen (Anämie), niedriger Anzahl weißer Blutkörperchen (Leukopenie) und/oder einer niedrigen Anzahl von Blutplättchen (Thrombozytopenie) verbunden. Anämie kann Schwäche verursachen, Leukopenie kann zu Infektionen führen und Thrombozytopenie kann die Blutgerinnung beeinträchtigen und zu verlängerten Blutungen führen

Leber-(Leber-)Komplikationen

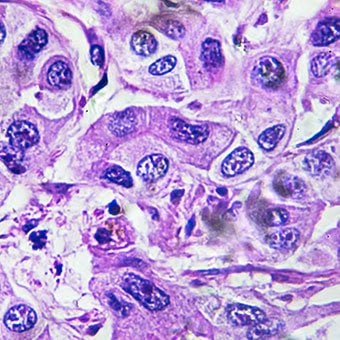

Leber-(Leber-)Komplikationen Zirrhose jeglicher Ursache erhöht das Risiko für primären Leberkrebs (hepatozelluläres Karzinom). Primär bezieht sich auf die Tatsache, dass der Tumor in der Leber entsteht. Ein sekundärer Leberkrebs ist ein Krebs, der an anderer Stelle im Körper entsteht und sich in die Leber ausbreitet (metastasiert).

Die häufigsten Symptome und Anzeichen von primärem Leberkrebs sind Bauchschmerzen und -schwellungen, eine vergrößerte Leber, Gewichtsverlust und Fieber. Darüber hinaus kann Leberkrebs eine Reihe von Substanzen produzieren und freisetzen, einschließlich solcher, die eine erhöhte Anzahl roter Blutkörperchen (Erythrozytose), einen niedrigen Blutzucker (Hypoglykämie) und einen hohen Kalziumspiegel im Blut (Hyperkalzämie) verursachen.

Ein Teil des Proteins in der Nahrung, das der Verdauung und Absorption entgeht, wird von Bakterien verwendet, die normalerweise im Darm vorhanden sind. Während sie das Protein für ihre eigenen Zwecke verwenden, stellen die Bakterien Substanzen her, die sie in den Darm abgeben, um dann vom Körper aufgenommen zu werden. Einige dieser Substanzen, wie Ammoniak, können toxische Wirkungen auf das Gehirn haben. Normalerweise werden diese toxischen Substanzen aus dem Darm in der Pfortader zur Leber transportiert, wo sie aus dem Blut entfernt und entgiftet werden.

Wenn eine Zirrhose vorliegt, können Leberzellen nicht normal funktionieren, entweder weil sie beschädigt sind oder weil sie ihre normale Beziehung zum Blut verloren haben. Außerdem umgeht ein Teil des Blutes in der Pfortader die Leber durch andere Venen. Das Ergebnis dieser Anomalien ist, dass toxische Substanzen nicht von den Leberzellen entfernt werden können und sich stattdessen im Blut anreichern.

Wenn sich die toxischen Substanzen ausreichend im Blut anreichern, wird die Funktion des Gehirns beeinträchtigt, ein Zustand, der als hepatische Enzephalopathie bezeichnet wird. Tagsüber statt nachts zu schlafen (Umkehrung des normalen Schlafmusters) ist ein frühes Symptom der hepatischen Enzephalopathie. Andere Symptome sind Reizbarkeit, Unfähigkeit, sich zu konzentrieren oder Berechnungen durchzuführen, Gedächtnisverlust, Verwirrtheit oder vermindertes Bewusstsein. Letztendlich führt eine schwere hepatische Enzephalopathie zu Koma und Tod.

Die toxischen Substanzen machen das Gehirn von Patienten mit Zirrhose auch sehr empfindlich gegenüber Medikamenten, die normalerweise von der Leber gefiltert und entgiftet werden. Die Dosis vieler Medikamente muss möglicherweise reduziert werden, um eine toxische Anhäufung bei Zirrhose zu vermeiden, insbesondere von Beruhigungsmitteln und Medikamenten zur Schlafförderung. Alternativ können Arzneimittel verwendet werden, die nicht über die Leber entgiftet oder aus dem Körper ausgeschieden werden müssen, wie z. B. Arzneimittel, die über die Nieren ausgeschieden werden.

Patienten mit sich verschlechternder Zirrhose können ein hepatorenales Syndrom entwickeln. Dieses Syndrom ist eine schwerwiegende Komplikation, bei der die Nierenfunktion eingeschränkt ist. Es ist ein funktionelles Problem in den Nieren, was bedeutet, dass die Nieren nicht körperlich geschädigt werden. Stattdessen ist die reduzierte Funktion auf Veränderungen in der Art und Weise zurückzuführen, wie das Blut durch die Nieren selbst fließt. Das hepatorenale Syndrom ist definiert als fortschreitendes Versagen der Nieren, Substanzen aus dem Blut zu entfernen und ausreichende Urinmengen zu produzieren, während andere wichtige Funktionen der Niere, wie z. B. die Salzretention, aufrechterhalten werden. Wenn sich die Leberfunktion verbessert oder einem Patienten mit hepatorenalem Syndrom eine gesunde Leber transplantiert wird, beginnen die Nieren normalerweise wieder normal zu arbeiten. Dies deutet darauf hin, dass die eingeschränkte Nierenfunktion entweder auf die Ansammlung toxischer Substanzen im Blut oder auf eine abnormale Leberfunktion bei Leberversagen zurückzuführen ist. Es gibt zwei Arten des hepatorenalen Syndroms. Ein Typ tritt allmählich über Monate auf. Der andere tritt schnell über ein oder zwei Wochen auf.

Selten können einige Patienten mit fortgeschrittener Zirrhose ein hepatopulmonales Syndrom entwickeln. Diese Patienten können unter Atembeschwerden leiden, da bestimmte Hormone, die bei einer fortgeschrittenen Zirrhose freigesetzt werden, eine abnormale Lungenfunktion verursachen. Das grundlegende Problem in der Lunge besteht darin, dass nicht genug Blut durch die kleinen Blutgefäße in der Lunge fließt, die mit den Alveolen (Lungenbläschen) der Lunge in Kontakt stehen. Das durch die Lunge fließende Blut wird um die Alveolen herumgeleitet und kann nicht genügend Sauerstoff aus der Luft in den Alveolen aufnehmen. Als Folge leidet der Patient unter Atemnot, insbesondere bei Anstrengung.

Es gibt 12 häufige Ursachen für Zirrhose.

Es gibt 12 häufige Ursachen für Zirrhose. Häufige Ursachen of cirrhosis of the liver include:

Less common causes of cirrhosis include:

In certain parts of the world (particularly Northern Africa), infection of the liver with a parasite (schistosomiasis) is the most common cause of liver disease and cirrhosis.

Alcohol and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease are common causes of cirrhosis.

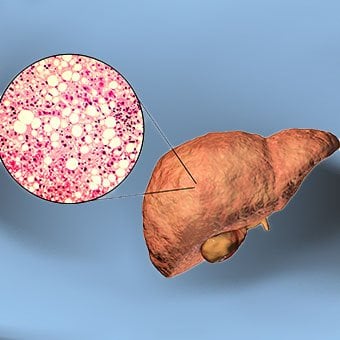

Alcohol and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease are common causes of cirrhosis. Alcohol is a very common cause of cirrhosis, particularly in the Western world. Chronic, high levels of alcohol consumption injure liver cells. Thirty percent of individuals who drink daily at least eight to sixteen ounces of hard liquor or the equivalent for fifteen or more years will develop cirrhosis. Alcohol causes a range of liver diseases, which include simple and uncomplicated fatty liver (steatosis), more serious fatty liver with inflammation (steatohepatitis or alcoholic hepatitis), and cirrhosis.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) refers to a wide spectrum of liver diseases that, like alcoholic liver disease, range from simple steatosis, to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), to cirrhosis. All stages of NAFLD have in common the accumulation of fat in liver cells. The term nonalcoholic is used because NAFLD occurs in individuals who do not consume excessive amounts of alcohol, yet in many respects the microscopic picture of NAFLD is similar to what can be seen in liver disease that is due to excessive alcohol. NAFLD is associated with a condition called insulin resistance, which, in turn, is associated with metabolic syndrome and diabetes mellitus type 2. Obesity is the main cause of insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes. NAFLD is the most common liver disease in the United States and is responsible for up to 25% of all liver disease. The number of livers transplanted for NAFLD-related cirrhosis is on the rise. Public health officials are worried that the current epidemic of obesity will dramatically increase the development of NAFLD and cirrhosis in the population.

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a liver disease caused by an abnormality of the immune system that is found predominantly in women.

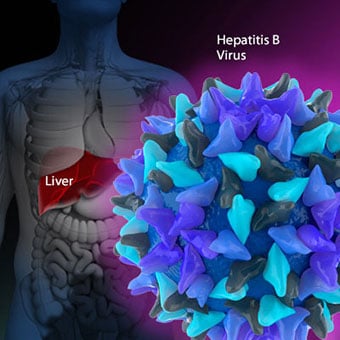

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a liver disease caused by an abnormality of the immune system that is found predominantly in women. Chronic viral hepatitis is a condition in which hepatitis B or hepatitis C virus infects the liver for years. Most patients with viral hepatitis will not develop chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis. The majority of patients infected with hepatitis A recover completely within weeks, without developing chronic infection. In contrast, some patients infected with hepatitis B virus and most patients infected with hepatitis C virus develop chronic hepatitis, which, in turn, causes progressive liver damage and leads to cirrhosis, and, sometimes, liver cancers.

Autoimmune hepatitis is a liver disease found more commonly in women that is caused by an abnormality of the immune system. The abnormal immune activity in autoimmune hepatitis causes progressive inflammation and destruction of liver cells (hepatocytes), leading ultimately to cirrhosis.

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a liver disease caused by an abnormality of the immune system that is found predominantly in women. The abnormal immunity in PBC causes chronic inflammation and destruction of the small bile ducts within the liver. The bile ducts are passages within the liver through which bile travels to the intestine. Bile is a fluid produced by the liver that contains substances required for digestion and absorption of fat in the intestine, as well as other compounds that are waste products, such as the pigment bilirubin. (Bilirubin is produced by the breakdown of hemoglobin from old red blood cells.). Along with the gallbladder, the bile ducts make up the biliary tract. In PBC, the destruction of the small bile ducts blocks the normal flow of bile into the intestine. As the inflammation continues to destroy more of the bile ducts, it also spreads to destroy nearby liver cells. As the destruction of the hepatocytes proceeds, scar tissue (fibrosis) forms and spreads throughout the areas of destruction. The combined effects of progressive inflammation, scarring, and the toxic effects of accumulating waste products culminates in cirrhosis.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is an uncommon disease frequently found in patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. In PSC, the large bile ducts outside of the liver become inflamed, narrowed, and obstructed. Obstruction to the flow of bile leads to infections of the bile ducts and jaundice, eventually causing cirrhosis. In some patients, injury to the bile ducts (usually because of surgery) also can cause obstruction and cirrhosis of the liver.

Different liver diseases should be diagnosed by specialists and different tests such as liver blood test, biopsy, and others.

Different liver diseases should be diagnosed by specialists and different tests such as liver blood test, biopsy, and others. Inherited (genetic) disorders that result in the accumulation of toxic substances in the liver, which leads to tissue damage and cirrhosis. Examples include the abnormal accumulation of iron (hemochromatosis) or copper (Wilson disease). In hemochromatosis, patients inherit a tendency to absorb an excessive amount of iron from food. Over time, iron accumulation in different organs throughout the body causes cirrhosis, arthritis, heart muscle damage leading to heart failure, and testicular dysfunction causing loss of sexual drive. Treatment is aimed at preventing damage to organs by removing iron from the body through phlebotomy (removing blood). In Wilson disease, there is an inherited abnormality in one of the proteins that control copper in the body. Over time, copper accumulates in the liver, eyes, and brain. Cirrhosis, tremor, psychiatric disturbances, and other neurological difficulties occur if the condition is not treated early. Treatment is with oral medication, which increases the amount of copper that is eliminated from the body in the urine.

Cryptogenic cirrhosis (cirrhosis due to unidentified causes) is a common reason for liver transplantation. It is termed called cryptogenic cirrhosis because for many years doctors have been being unable to explain why a proportion of patients developed cirrhosis. Doctors now believe that cryptogenic cirrhosis is due to NASH (nonalcoholic steatohepatitis) caused by long-standing obesity, type 2 diabetes, and insulin resistance. The fat in the liver of patients with NASH is believed to disappear with the onset of cirrhosis, and this has made it difficult for doctors to make the connection between NASH and cryptogenic cirrhosis for a long time. One important clue that NASH leads to cryptogenic cirrhosis is the finding of a high occurrence of NASH in the new livers of patients undergoing liver transplant for cryptogenic cirrhosis. Finally, a study from France suggests that patients with NASH have a similar risk of developing cirrhosis as patients with long-standing infection with hepatitis C virus. (See discussion that follows.) However, the progression to cirrhosis from NASH is thought to be slow and the diagnosis of cirrhosis typically is made in people in their sixties.

Infants can be born without bile ducts (biliary atresia) and ultimately develop cirrhosis. Other infants are born lacking vital enzymes for controlling sugars that lead to the accumulation of sugars and cirrhosis. On rare occasions, the absence of a specific enzyme can cause cirrhosis and scarring of the lung (alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency).

Less common causes of cirrhosis include unusual reactions to some drugs and prolonged exposure to toxins, as well as chronic heart failure (cardiac cirrhosis). In certain parts of the world (particularly Northern Africa), infection of the liver with a parasite (schistosomiasis) is the most common cause of liver disease and cirrhosis.

Different liver diseases should be diagnosed by specialists and different tests such as liver blood test, biopsy, and others.

Different liver diseases should be diagnosed by specialists and different tests such as liver blood test, biopsy, and others. The single best test for diagnosing cirrhosis is a biopsy of the liver. Liver biopsies carry a small risk for serious complications, and biopsy often is reserved for those patients in whom the diagnosis of the type of liver disease or the presence of cirrhosis is not clear. The history, physical examination, or routine testing may suggest the possibility of cirrhosis. If cirrhosis is present, other tests can be used to determine the severity of the cirrhosis and the presence of complications. Tests also may be used to diagnose the underlying disease that is causing the cirrhosis. Examples of how doctors diagnose and evaluate cirrhosis are:

There are four types of treatment of cirrhosis.

There are four types of treatment of cirrhosis. Treatment of cirrhosis includes

Consume a balanced diet and one multivitamin daily. Patients with PBC with impaired absorption of fat-soluble vitamins may need additional vitamins D and K.

Avoid drugs (including alcohol) that cause liver damage. All patients with cirrhosis should avoid alcohol. Most patients with alcohol-induced cirrhosis experience an improvement in liver function with abstinence from alcohol. Even patients with chronic hepatitis B and C can substantially reduce liver damage and slow the progression towards cirrhosis with abstinence from alcohol.

Avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, e.g., ibuprofen). Patients with cirrhosis can experience worsening of liver and kidney function with NSAIDs.

Eradicate hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus by using anti-viral medications. Not all patients with cirrhosis due to chronic viral hepatitis are candidates for drug treatment. Some patients may experience serious deterioration in liver function and/or intolerable side effects during treatment. Thus, decisions to treat viral hepatitis have to be individualized, after consulting with doctors experienced in treating liver diseases (hepatologists).

Remove blood from patients with hemochromatosis to reduce the levels of iron and prevent further damage to the liver. In Wilson's disease, medications can be used to increase the excretion of copper in the urine to reduce the levels of copper in the body and prevent further damage to the liver.

Suppress the immune system with drugs such as prednisone and azathioprine (Imuran) to decrease inflammation of the liver in autoimmune hepatitis.

Treat patients with PBC with a bile acid preparation, ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), also called ursodiol (Actigall). Results of an analysis that combined the results from several clinical trials showed that UDCA increased survival among PBC patients during 4 years of therapy. The development of portal hypertension also was reduced by the UDCA. It is important to note that despite producing clear benefits, UDCA treatment primarily retards progression and does not cure PBC. Other medications such as colchicine and methotrexate also may have benefits in subsets of patients with PBC.

Immunize patients with cirrhosis against infection with hepatitis A and B to prevent a serious deterioration in liver. There are currently no vaccines available for immunizing against hepatitis C.

Treatment for edema, ascites, and hypersplenism complications.

Treatment for edema, ascites, and hypersplenism complications. Retaining salt and water can lead to swelling of the ankles and legs (edema) or abdomen (ascites) in patients with cirrhosis. Doctors often advise patients with cirrhosis to restrict dietary salt (sodium) and fluid to decrease edema and ascites. The amount of salt in the diet usually is restricted to 2 grams per day and fluid to 1.2 liters per day. In most patients with cirrhosis, salt and fluid restriction is not enough and diuretics have to be added.

Diuretics are medications that work in the kidneys to promote the elimination of salt and water into the urine. A combination of the diuretics spironolactone (Aldactone) and furosemide (Lasix) can reduce or eliminate the edema and ascites in most patients. During treatment with diuretics, it is important to monitor the function of the kidneys by measuring blood levels of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine to determine if too much diuretic is being used. Too much diuretic can lead to kidney dysfunction that is reflected in elevations of the BUN and creatinine levels in the blood.

Sometimes, when the diuretics do not work (in which case the ascites is said to be refractory), a long needle or catheter is used to draw out the ascitic fluid directly from the abdomen, a procedure called abdominal paracentesis. It is common to withdraw large amounts (liters) of fluid from the abdomen when the ascites is causing painful abdominal distension and/or difficulty breathing because it limits the movement of the diaphragms.

Another treatment for refractory ascites is a procedure called transjugular intravenous portosystemic shunting (TIPS).

The spleen normally acts as a filter to remove older red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets (small particles important for the clotting of blood). The blood that drains from the spleen joins the blood in the portal vein from the intestines. As the pressure in the portal vein rises in cirrhosis, it increasingly blocks the flow of blood from the spleen. The blood "backs-up," accumulating in the spleen, and the spleen swells in size, a condition referred to as splenomegaly. Sometimes, the spleen is so enlarged it causes abdominal pain.

As the spleen enlarges, it filters out more and more of the blood cells and platelets until their numbers in the blood are reduced. Hypersplenism is the term used to describe this condition, and it is associated with a low red blood cell count (anemia), low white blood cell count (leukopenia), and/or a low platelet count (thrombocytopenia). Anemia can cause weakness, leucopenia can lead to infections, and thrombocytopenia can impair the clotting of blood and result in prolonged bleeding.

Once varices have bled, they tend to rebleed and the probability that a patient will die from each bleeding episode is high (30% to 35%). Treatment is necessary to prevent the first bleeding episode as well as rebleeding.

Once varices have bled, they tend to rebleed and the probability that a patient will die from each bleeding episode is high (30% to 35%). Treatment is necessary to prevent the first bleeding episode as well as rebleeding. If large varices develop in the esophagus or upper stomach, patients with cirrhosis are at risk for serious bleeding due to rupture of these varices. Once varices have bled, they tend to rebleed and the probability that a patient will die from each bleeding episode is high (30% to 35%). Treatment is necessary to prevent the first bleeding episode as well as rebleeding. Treatments include medications and procedures to decrease the pressure in the portal vein and procedures to destroy the varices.

Hepatic encephalopathy usually should be treated with a low protein diet and oral lactulose.

Hepatic encephalopathy usually should be treated with a low protein diet and oral lactulose. Patients with an abnormal sleep cycle, impaired thinking, odd behavior, or other signs of hepatic encephalopathy usually should be treated with a low protein diet and oral lactulose. Dietary protein is restricted because it is a source of toxic compounds that cause hepatic encephalopathy. Lactulose, which is a liquid, traps toxic compounds in the colon so they cannot be absorbed into the bloodstream, and thus cause encephalopathy. Lactulose is converted to lactic acid in the colon, and the acidic environment that results is believed to trap the toxic compounds produced by the bacteria. To be sure adequate lactulose is present in the colon at all times, the patient should adjust the dose to produce 2 to 3 semiformed bowel movements a day. Lactulose is a laxative, and the effectiveness of treatment can be judged by loosening or increasing the frequency of stools. Rifaximin (Xifaxan) is an antibiotic taken orally that is not absorbed into the body but rather remains in the intestines. It is the preferred mode of treatment of hepatic encephalopathy. Antibiotics work by suppressing the bacteria that produce the toxic compounds in the colon.

Most patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis are hospitalized and treated with intravenous antibiotics.

Most patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis are hospitalized and treated with intravenous antibiotics. Patients suspected of having spontaneous bacterial peritonitis usually will undergo paracentesis. The fluid that is removed is examined for white blood cells and cultured for bacteria. Culturing involves inoculating a sample of the ascites into a bottle of nutrient-rich fluid that encourages the growth of bacteria, thus facilitating the identification of even small numbers of bacteria. Blood and urine samples also are often obtained for culturing because many patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis also will have infections in their blood and urine. Many doctors believe the infection may have begun in the blood and the urine and spread to the ascitic fluid to cause spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Most patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis are hospitalized and treated with intravenous antibiotics such as cefotaxime (Claforan). Patients usually treated with antibiotics include:

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is a serious infection. It often occurs in patients with advanced cirrhosis whose immune systems are weak, but with modern antibiotics and early detection and treatment, the prognosis of recovering from an episode of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is good.

In some patients, oral antibiotics (norfloxacin [Noroxin] or sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim [Bactrim]) can be prescribed to prevent spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Not all patients with cirrhosis and ascites should be treated with antibiotics to prevent spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, but some patients are at high risk for developing spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and warrant preventive treatment.

The prognosis and life expectancy for cirrhosis of the liver varies and depends on the cause, the severity, any complications, and any underlying diseases.

The prognosis and life expectancy for cirrhosis of the liver varies and depends on the cause, the severity, any complications, and any underlying diseases. Several types of liver disease that cause cirrhosis (such as hepatitis B and C) are associated with a high incidence of liver cancer. It is useful to screen for liver cancer in patients with cirrhosis, as early surgical treatment or transplantation of the liver can cure the patient of cancer. The difficulty is that the methods available for screening are only partially effective, identifying at best only half of patients at a curable stage of their cancer. Despite the partial effectiveness of screening, most patients with cirrhosis, particularly hepatitis B and C, are screened yearly or every six months with ultrasound examination of the liver and measurements of cancer-produced proteins in the blood, for example, alpha-fetoprotein.

Cirrhosis is irreversible. Liver function usually gradually worsens despite treatment, and complications of cirrhosis increase and become difficult to treat. When cirrhosis is far advanced liver transplantation often is the only option for treatment. Recent advances in surgical transplantation and medications to prevent infection and rejection of the transplanted liver have greatly improved survival after transplantation. On average, more than 80% of patients who receive transplants are alive after five years. Not everyone with cirrhosis is a candidate for transplantation. Furthermore, there is a shortage of livers to transplant, and they're usually is a long (months to years) wait before a liver for transplanting becomes available. Measures to slow the progression of liver disease, and treat and prevent complications of cirrhosis are vitally important.

The prognosis and life expectancy for cirrhosis of the liver varies and depends on the cause, the severity, any complications, and any underlying diseases.

Progress in the management and prevention of cirrhosis continues. Research is ongoing to determine the mechanism of scar formation in the liver and how this process of scarring can be interrupted or even reversed. Newer and better treatments for viral liver disease are being developed to prevent the progression to cirrhosis. Prevention of viral hepatitis by vaccination, which is available for hepatitis B, is being developed for hepatitis C. Treatments for the complications of cirrhosis are being developed or revised, and tested continually. Finally, research is being directed at identifying new proteins in the blood that can detect liver cancer early or predict which patients will develop liver cancer.

Säurereflux während der Chemotherapie

Säurereflux – wenn Magensäure oder Galle aus dem Magen in die Speiseröhre aufsteigen, was zu Reizungen führt – ist im Allgemeinen eine häufige Verdauungsstörung, aber Ihr Risiko dafür steigt wenn Sie

Säurereflux während der Chemotherapie

Säurereflux – wenn Magensäure oder Galle aus dem Magen in die Speiseröhre aufsteigen, was zu Reizungen führt – ist im Allgemeinen eine häufige Verdauungsstörung, aber Ihr Risiko dafür steigt wenn Sie

FDA warnt vor Eierstockkrebstests als nicht zuverlässig

Neueste Krebsnachrichten Sie müssen kein Raucher sein, um an Lungenkrebs zu erkranken Fortschritt bei Lungenkrebs führt zu allgemeinem Rückgang Immunbasiertes Medikament bekämpft Endometriumkarzinom

FDA warnt vor Eierstockkrebstests als nicht zuverlässig

Neueste Krebsnachrichten Sie müssen kein Raucher sein, um an Lungenkrebs zu erkranken Fortschritt bei Lungenkrebs führt zu allgemeinem Rückgang Immunbasiertes Medikament bekämpft Endometriumkarzinom

Die 7 besten Fette für einen gesunden Darm (und 5 zu vermeidende)

Ein paar schnelle Fakten über Fett: Fett ist einer der 3 Makronährstoffe in unserer Nahrung (die anderen beiden sind Eiweiß und Kohlenhydrate) Fett enthält 9 Kalorien pro Gramm (Eiweiß und Kohlenhydr

Die 7 besten Fette für einen gesunden Darm (und 5 zu vermeidende)

Ein paar schnelle Fakten über Fett: Fett ist einer der 3 Makronährstoffe in unserer Nahrung (die anderen beiden sind Eiweiß und Kohlenhydrate) Fett enthält 9 Kalorien pro Gramm (Eiweiß und Kohlenhydr