Un mâle adulte pointant vers un contour de foie et peint une vésicule biliaire sur son abdomen.

Un mâle adulte pointant vers un contour de foie et peint une vésicule biliaire sur son abdomen. Les symptômes d'une attaque de la vésicule biliaire incluent :

Illustration du système digestif avec des calculs biliaires et gros plan de calculs biliaires dans la vésicule biliaire une pierre qui est également passée dans le canal cystique.

Illustration du système digestif avec des calculs biliaires et gros plan de calculs biliaires dans la vésicule biliaire une pierre qui est également passée dans le canal cystique. Les calculs biliaires (souvent mal orthographiés comme calculs biliaires) sont des calculs qui se forment dans la bile (bile) dans la vésicule biliaire. (La vésicule biliaire est un organe en forme de poire juste en dessous du foie qui stocke la bile sécrétée par le foie.) Les calculs biliaires atteignent une taille comprise entre un seizième de pouce et plusieurs pouces.

De la voie biliaire, la bile peut s'écouler de deux directions différentes.

Une fois dans la vésicule biliaire, la bile est concentrée par l'élimination (absorption) de l'eau. Au cours d'un repas, le muscle qui constitue la paroi de la vésicule biliaire se contracte et comprime la bile concentrée dans la vésicule biliaire à travers le canal cystique dans le canal cholédoque, puis dans l'intestin. (La bile concentrée est beaucoup plus efficace pour la digestion que la bile non concentrée qui va du foie directement dans l'intestin.) Le moment de la contraction de la vésicule biliaire - pendant un repas - permet à la bile concentrée de la vésicule biliaire de se mélanger à la nourriture.

Les calculs biliaires se forment généralement dans la vésicule biliaire; cependant, ils peuvent également se former partout où il y a de la bile - dans les canaux intra-hépatiques, hépatiques, cholédoques et cystiques.

Les calculs biliaires peuvent également se déplacer dans la bile, par exemple, de la vésicule biliaire dans le conduit cystique ou commun.

Un homme souffre de coliques biliaires. Le symptôme le plus courant des calculs biliaires est la colique biliaire.

Un homme souffre de coliques biliaires. Le symptôme le plus courant des calculs biliaires est la colique biliaire. La majorité des personnes atteintes de calculs biliaires ne présentent aucun signe ou symptôme et ne sont pas conscientes de leurs calculs biliaires. (Les calculs biliaires sont "silencieux".) Ces calculs biliaires sont souvent découverts à la suite de tests (par exemple, échographie ou radiographie de l'abdomen) effectués lors de l'évaluation de conditions médicales autres que les calculs biliaires. Cependant, les symptômes peuvent apparaître plus tard dans la vie, après de nombreuses années sans symptômes. Ainsi, sur une période de cinq ans, environ 10 % des personnes atteintes de calculs biliaires silencieux développeront des symptômes. Une fois que les symptômes se développent, ils sont susceptibles de persister et souvent de s'aggraver.

Lorsque des signes et des symptômes de calculs biliaires apparaissent, ils se produisent pratiquement toujours parce que les calculs biliaires obstruent les voies biliaires.

Le symptôme le plus courant des calculs biliaires est la colique biliaire. La colique biliaire est un type de douleur très spécifique, survenant comme symptôme principal ou unique chez 80% des personnes atteintes de calculs biliaires qui développent des symptômes. La colique biliaire survient lorsque les voies biliaires (canaux cystiques, hépatiques ou canaux cholédoques) sont soudainement obstruées par un calcul biliaire. Une obstruction d'évolution lente, comme à partir d'une tumeur, ne provoque pas de colique biliaire. Derrière l'obstruction, le liquide s'accumule et distend les conduits et la vésicule biliaire. En cas d'obstruction du canal hépatique ou du canal biliaire principal, cela est dû à la sécrétion continue de bile par le foie. Dans le cas d'une obstruction du canal cystique, la paroi de la vésicule biliaire sécrète du liquide dans la vésicule biliaire. La distension des canaux ou de la vésicule biliaire provoque des coliques biliaires.

De manière caractéristique, les coliques biliaires surviennent soudainement ou s'accumulent rapidement pour atteindre un pic en quelques minutes.

La colique biliaire est un symptôme récurrent. Une fois le premier épisode survenu, il y aura probablement d'autres épisodes. De plus, il existe un schéma de récurrence pour chaque individu, c'est-à-dire que chez certains individus, les épisodes ont tendance à rester fréquents tandis que chez d'autres, ils sont peu fréquents. La majorité des personnes qui développent des coliques biliaires ne développent pas de cholécystite ou d'autres complications. Il existe une idée fausse selon laquelle la contraction de la vésicule biliaire est à l'origine de l'obstruction des canaux et des coliques biliaires. Manger, même des aliments gras, ne provoque pas de coliques biliaires; la plupart des épisodes de coliques biliaires surviennent pendant la nuit, longtemps après que la vésicule biliaire se soit vidée.

Les calculs biliaires sont responsables de nombreux symptômes qu'ils ne provoquent pas. Parmi les symptômes, les calculs biliaires ne provoquent pas sont :

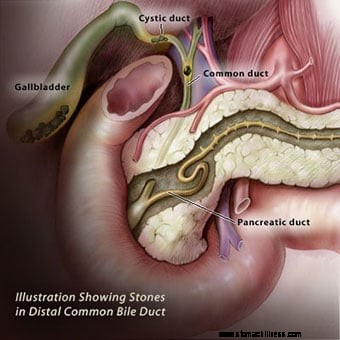

Illustration montrant des calculs biliaires dans la vésicule biliaire ainsi que dans le canal cholédoque distal. Le canal cholédoque a une paroi musculaire.

Illustration montrant des calculs biliaires dans la vésicule biliaire ainsi que dans le canal cholédoque distal. Le canal cholédoque a une paroi musculaire. L'ablation de la vésicule biliaire (cholécystectomie) devrait éliminer tous les symptômes liés aux calculs biliaires, sauf dans trois situations :

La possibilité de calculs biliaires dans les conduits peut être poursuivie avec MRCP, échographie endoscopique et ERCP. Rarement, des symptômes semblables à des calculs biliaires peuvent être causés par une affection appelée dysfonctionnement du sphincter d'Oddi, décrite ci-dessous.

Le canal cholédoque a une paroi musculaire. Les derniers centimètres du muscle du canal cholédoque immédiatement avant que le canal ne rejoigne le duodénum comprennent le sphincter d'Oddi. Le sphincter d'Oddi contrôle le flux de bile. Étant donné que le canal pancréatique rejoint généralement le canal cholédoque peu de temps avant son entrée dans le duodénum, le sphincter contrôle également le flux de liquide provenant du canal pancréatique. Lorsque le muscle du sphincter se resserre, il coupe le flux de bile et de liquide pancréatique. Lorsqu'il se détend, la bile et le liquide pancréatique s'écoulent à nouveau dans le duodénum, par exemple après un repas. Le sphincter peut devenir cicatrisé et le conduit est rétréci par la cicatrisation. (La cause de la cicatrisation est inconnue.) Le sphincter peut également avoir des spasmes par intermittence. Dans les deux cas, l'écoulement de la bile et du liquide pancréatique peut s'arrêter brusquement par intermittence, imitant les effets d'un calcul biliaire provoquant des coliques biliaires et une pancréatite.

Le diagnostic de dysfonctionnement du sphincter d'Oddi peut être difficile à poser. Le meilleur test de diagnostic nécessite une procédure endoscopique avec le même type d'endoscope que la CPRE. Au lieu de remplir les conduits de colorant, cependant, la pression à l'intérieur du sphincter est mesurée. Si la pression est anormalement élevée, des cicatrices ou des spasmes du sphincter sont probables. Le traitement du dysfonctionnement du sphincter d'Oddi est la sphinctérotomie (décrite précédemment). La mesure des enzymes hépatiques et pancréatiques dans le sang peut également être utile pour diagnostiquer un dysfonctionnement du sphincter.

Collection de calculs biliaires de différentes tailles et formes.

Collection de calculs biliaires de différentes tailles et formes. Les calculs biliaires peuvent être au nombre de un à des centaines, dont la taille varie d'un millimètre à quatre ou cinq centimètres. Lorsqu'il n'y a qu'un ou quelques calculs biliaires, ils ont tendance à être ronds. Lorsqu'un plus grand nombre de calculs biliaires sont présents, ils ont tendance à être facettés en raison du frottement d'un calcul biliaire contre un autre. Les calculs biliaires à pigment brun peuvent être friables et irréguliers.

Les calculs biliaires peuvent sortir de la vésicule biliaire ou des conduits, en particulier s'ils sont petits. C'est le passage des calculs biliaires qui entraîne bon nombre de leurs complications.

Les calculs biliaires sont courants ; ils surviennent chez environ 20% des femmes aux États-Unis, au Canada et en Europe, mais il existe une grande variation dans la prévalence entre les différents groupes ethniques. Par exemple, les calculs biliaires surviennent 1 ½ à 2 fois plus fréquemment chez les Scandinaves et les Américains d'origine mexicaine. Chez les Indiens d'Amérique, la prévalence des calculs biliaires est supérieure à 80 %. Ces différences s'expliquent probablement par des facteurs génétiques (héréditaires). Les parents au premier degré (parents, frères et sœurs et enfants) des personnes atteintes de calculs biliaires sont 1 fois et demie plus susceptibles d'avoir des calculs biliaires que s'ils n'ont pas de parent au premier degré avec des calculs biliaires. Un soutien supplémentaire à une prédisposition génétique provient d'études sur les jumeaux. Ainsi, parmi les paires de jumeaux non identiques (qui partagent 50 % de leurs gènes), les deux individus d'une paire ont des calculs biliaires 8 % du temps. Parmi les paires identiques de jumeaux (qui partagent 100 % de leurs gènes), les deux individus ont des calculs biliaires 23 % du temps.

Plusieurs conditions sont associées à la formation de calculs biliaires, et la manière dont elles provoquent des calculs biliaires peut varier. (Voir risques de calculs biliaires.)

Les calculs biliaires de cholestérol sont principalement constitués de cholestérol. Il existe deux autres processus qui favorisent la formation de calculs biliaires de cholestérolIl existe plusieurs types de calculs biliaires, et chaque type a une cause différente.

Les calculs biliaires de cholestérol sont principalement constitués de cholestérol. Il s'agit du type de calculs biliaires le plus courant, représentant 80 % des calculs biliaires chez les individus en Europe et dans les Amériques. Le cholestérol est l'une des substances (produits chimiques) que les cellules du foie sécrètent dans la bile. La sécrétion de cholestérol dans la bile est un mécanisme important par lequel le foie élimine l'excès de cholestérol de l'organisme.

Pour que la bile transporte le cholestérol, le cholestérol doit être dissous dans la bile. Cependant, le cholestérol est de la graisse et la bile est une solution aqueuse ou aqueuse; les graisses ne se dissolvent pas dans les solutions aqueuses. Afin de dissoudre le cholestérol dans la bile, le foie sécrète également deux détergents, les acides biliaires et la lécithine, dans la bile. Ces détergents, tout comme les détergents à vaisselle, dissolvent le cholestérol gras afin qu'il puisse être transporté par la bile à travers les conduits. Si le foie sécrète trop de cholestérol pour le nombre d'acides biliaires et de lécithine qu'il sécrète, une partie du cholestérol ne reste pas dissoute. De même, si le foie ne sécrète pas suffisamment d'acides biliaires et de lécithine, une partie du cholestérol ne reste pas dissoute. Dans les deux cas, le cholestérol non dissous se colle et forme des particules de cholestérol qui grossissent et finissent par devenir des calculs biliaires.

Deux autres processus favorisent la formation de calculs biliaires de cholestérol bien qu'aucun processus ne soit capable de provoquer la formation de calculs biliaires de cholestérol.

Les calculs biliaires pigmentaires sont le deuxième type de calculs biliaires le plus courant.

Les calculs biliaires pigmentaires sont le deuxième type de calculs biliaires le plus courant. Les calculs biliaires pigmentaires sont le deuxième type de calculs biliaires le plus courant. Bien que les calculs biliaires pigmentaires ne représentent que 15 % des calculs biliaires chez les individus d'Europe et des Amériques, ils sont plus fréquents que les calculs biliaires de cholestérol en Asie du Sud-Est. Il existe deux types de calculs biliaires pigmentés :1) les calculs biliaires pigmentés noirs et 2) les calculs biliaires pigmentés bruns.

Le pigment est un déchet formé à partir de l'hémoglobine, le produit chimique transportant l'oxygène dans les globules rouges. L'hémoglobine des vieux globules rouges qui sont détruits est transformée en une substance chimique appelée bilirubine et libérée dans le sang. La bilirubine est éliminée du sang par le foie. Le foie modifie la bilirubine et sécrète la bilirubine modifiée dans la bile afin qu'elle puisse être éliminée du corps.

Calculs biliaires à pigment noir : S'il y a trop de bilirubine dans la bile, la bilirubine se combine avec d'autres constituants de la bile, par exemple le calcium, pour former un pigment (appelé ainsi parce qu'il est de couleur brun foncé). Le pigment se dissout mal dans la bile et, comme le cholestérol, il se colle et forme des particules qui grossissent et finissent par devenir des calculs biliaires. Les calculs biliaires pigmentés qui se forment de cette manière sont appelés calculs biliaires pigmentés noirs car ils sont noirs et durs.

Calculs biliaires pigmentaires bruns : S'il y a une contraction réduite de la vésicule biliaire ou une obstruction à l'écoulement de la bile dans les conduits, les bactéries peuvent remonter du duodénum dans les voies biliaires et la vésicule biliaire. Les bactéries modifient la bilirubine dans les conduits et la vésicule biliaire, et la bilirubine altérée se combine ensuite avec le calcium pour former un pigment. Le pigment se combine ensuite avec les graisses de la bile (cholestérol et acides gras de la lécithine) pour former des particules qui se transforment en calculs biliaires. Ce type de calcul biliaire est appelé calcul biliaire à pigment brun car il est plus brun que noir. Il est également plus doux que les calculs biliaires à pigment noir.

Autres types de calculs biliaires. Les autres types de calculs biliaires sont rares. Le type le plus intéressant est peut-être le calcul biliaire qui se forme chez les patients prenant l'antibiotique ceftriaxone (Rocephin). La ceftriaxone est inhabituelle en ce sens qu'elle est éliminée du corps dans la bile à des concentrations élevées. Il se combine avec le calcium dans la bile et devient insoluble. Comme le cholestérol et les pigments, la ceftriaxone insoluble et le calcium forment des particules qui se transforment en calculs biliaires. Heureusement, la plupart de ces calculs biliaires disparaissent une fois l'antibiotique arrêté; cependant, ils peuvent encore causer des problèmes jusqu'à ce qu'ils disparaissent. Un autre type rare de calculs biliaires est formé de carbonate de calcium.

The eight risk factors for developing cholesterol gallstones include gender, age, obesity, pregnancy, birth control pills and hormone therapy, rapid weight loss, Crohn's disease, and increased blood triglycerides.

The eight risk factors for developing cholesterol gallstones include gender, age, obesity, pregnancy, birth control pills and hormone therapy, rapid weight loss, Crohn's disease, and increased blood triglycerides. There is no relationship between cholesterol in the blood and cholesterol gallstones. Individuals with elevated blood cholesterol do not have an increased prevalence of cholesterol gallstones. A common misconception is that diet is responsible for the development of cholesterol gallstones, however, it isn't. The eight risk factors for developing cholesterol gallstones include:

A female doctor sits next to an ultrasound machine.

A female doctor sits next to an ultrasound machine. Gallstones are diagnosed in one of two situations.

Ultrasonography is the most important means of diagnosing gallstones. Standard computerized tomography (CT or CAT scan) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may occasionally demonstrate gallstones; however, they are not as useful compared to ultrasonography because they miss gallstones.

Ultrasonography is a radiological technique that uses high-frequency sound waves to produce images of the organs and structures of the body. The sound waves are emitted from a device called a transducer and are sent through the body's tissues. The sound waves are reflected by the surfaces and interiors of internal organs and structures as "echoes." These echoes return to the transducer and are transmitted onto a viewing monitor. On the monitor, the outline of organs and structures can be determined as well as their consistency, for example, liquid or solid.

Two types of ultrasonographic techniques can be used for diagnosing gallstones:transabdominal ultrasonography and endoscopic ultrasonography.

For transabdominal ultrasonography, the transducer is placed directly on the skin of the abdomen. The sound waves travel through the skin and then into the abdominal organs. Transabdominal ultrasonography is painless, inexpensive, and without risk to the patient. In addition to identifying 97% of gallstones in the gallbladder, abdominal ultrasonography can identify many other abnormalities related to gallstones. It can identify:

Transabdominal ultrasonography also may identify diseases not related to gallstones that may be the cause of the patient's problem, for example, appendicitis. The limitations of transabdominal ultrasonography are that it can only identify gallstones larger than 4-5 millimeters in size, and it is poor at identifying gallstones in the bile ducts.

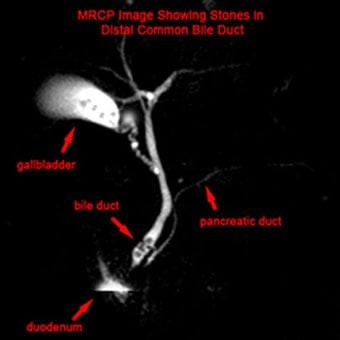

MRCP image showing stones in the common bile duct:(a) Gallbladder with stones (b) Stone in bile duct (c) Pancreatic duct (d) Duodenum.

MRCP image showing stones in the common bile duct:(a) Gallbladder with stones (b) Stone in bile duct (c) Pancreatic duct (d) Duodenum. For endoscopic ultrasonography, a long flexible tube - the endoscope - is swallowed by the patient after he or she has been sedated with intravenous medication. The tip of the endoscope is fitted with an ultrasound transducer. The transducer is advanced into the duodenum where ultrasonographic images are obtained.

Endoscopic ultrasonography can identify gallstones and the same abnormalities as transabdominal ultrasonography; however, since the transducer is much closer to the structures of interest - the gallbladder, bile ducts, and pancreas - better images are obtained than with transabdominal ultrasonography. Thus, it is possible to visualize smaller gallstones with EUS than transabdominal ultrasonography. EUS also is better at identifying gallstones in the common bile duct.

Although endoscopic ultrasonography is in many ways better than transabdominal ultrasonography, it is expensive, not available everywhere, and carries a small risk of complications such as those associated with the use of intravenous sedation, and intestinal perforation by the endoscope. Fortunately, transabdominal ultrasonography usually gives most of the necessary information, and endoscopic ultrasonography is needed only infrequently. Endoscopic ultrasonography also is a better way than transabdominal ultrasonography to evaluate the pancreas for pancreatitis or its complications.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography or MRCP is a modification of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) that allows the bile and pancreatic ducts to be examined.

The procedure is called cholangitis (referring to the bile ducts) pancreatography (referring to the pancreatic duct) because it can demonstrate the bile and pancreatic ducts.

MRCP has in many instances replaced other procedures such as cholescintigraphy (HIDA scan) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for evaluating the bile ducts. It can identify gallstones in the bile ducts, obstruction of the ducts, and leaks of bile. There are no risks to the patient with MRCP except for very rare reactions to the injected dye.

Normal hepatobiliary scan (HIDA scan) showing a series of scans done over time to see where bile is excreted and/or accumulated.

Normal hepatobiliary scan (HIDA scan) showing a series of scans done over time to see where bile is excreted and/or accumulated. Cholescintigraphy is a procedure done by nuclear medicine physicians. It also is referred to as a HIDA scan or a gallbladder scan.

HIDA scans are used to identify obstruction of the bile ducts, for example, by a gallstone. They also may identify bile leaks and fistulas. There are no risks to the patient with HIDA scans.

Cholescintigraphy also is used to study the emptying of the gallbladder. Some patients with gallstones have had gallbladder inflammation due to recognized or unrecognized episodes of cholecystitis. (There also are uncommon, non-gallstone-related causes of inflammation of the gallbladder.) The inflammation can result in scarring of the gallbladder's wall and muscle, which reduces the ability of the gallbladder to contract. As a result, the gallbladder does not empty normally. During cholescintigraphy, a synthetic hormone related to cholecystokinin (the hormone the body produces and releases during a meal to cause the gallbladder to contract) can be injected intravenously to cause the gallbladder to contract and squeeze out its bile and radioactivity into the intestine. If the gallbladder does not empty the bile and radioactivity normally, it is assumed that the gallbladder is diseased due to gallstones or non-gallstone-related inflammation.

The problem with interpreting a gallbladder emptying study is that many people with normal gallbladders have abnormal emptying of the gallbladder. Therefore, it is hazardous to base a diagnosis of a diseased gallbladder on abnormal gallbladder emptying alone.

The doctor performs an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) on a woman for gallstones.

The doctor performs an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) on a woman for gallstones. ERCP is a combined endoscope and X-ray procedure performed to examine the duodenum (the first portion of the small intestine), the papilla of Vater (a small nipple-like structure where the common bile and pancreatic ducts enter the duodenum), the gallbladder, and bile and pancreatic ducts.

The procedure is performed by using a long, flexible, side-viewing instrument (a duodenoscope, a type of endoscope) about the diameter of a fountain pen. The duodenoscope is flexible and can be directed and moved around the many bends of the stomach and intestine. The video-endoscope is the most common type of duodenoscope and uses a chip at the tip of the instrument to transmit video images to a TV screen.

ERCP can identify; 1) gallstones in the gallbladder (though it is not particularly good at this) and 2) blockage of the bile ducts, for example, by gallstones, and 3) bile leaks. ERCP also may identify diseases not related to gallstones that may be the cause of the patient's problem, for example, pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer.

An important advantage of ERCP is that instruments can be passed through the same channel as the cannula used to inject the dye to extract gallstones stuck in the common and hepatic ducts. This can save the patient from having an operation. ERCP has several risks associated with it, including the drugs used for sedation, perforation of the duodenum by the duodenoscope, and pancreatitis (due to damage to the pancreas). If gallstones are extracted, bleeding also may occur as a complication.

A doctor holding an anatomical model of the human liver and pointing to a gallstone.

A doctor holding an anatomical model of the human liver and pointing to a gallstone. When the liver or pancreas becomes inflamed or their ducts become obstructed and enlarged, the cells of the liver and pancreas release some of their enzymes into the blood. The most commonly measured liver enzymes in blood are aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT). The most commonly-measured pancreatic enzymes in blood are amylase and lipase. Many medical conditions that affect the liver or pancreas cause these blood tests to become abnormal, so these abnormalities alone cannot be used to diagnose gallstones. Nevertheless, abnormalities of these tests suggest there is a problem with the liver, bile ducts, or pancreas, and gallstones are a common cause of such abnormal tests, particularly during sudden obstruction of the bile ducts or pancreatic ducts. Thus, abnormal liver and pancreatic blood test direct attention to the possibility that gallstones may be causing the acute problem.

Duodenal biliary drainage is a procedure that occasionally can be useful in diagnosing gallstones; however, it is not often used. As previously discussed, gallstones begin as microscopic particles of cholesterol or pigment that grow in size. It is clear that some people who develop biliary colic, cholecystitis, or pancreatitis have only these particles in their gallbladders, yet the particles are too small to obstruct the ducts. There are two potential explanations for how obstruction might occur in this situation. The first is that a small gallstone initially caused an obstruction before passing through the bile ducts into the intestine. The second is that particles passing through the bile ducts can "irritate" the ducts, causing spasm of the muscle within the walls of the ducts (which obstructs the flow of bile) or inflammation of the duct that causes the wall of the duct to swell (which also obstructs the duct).

The risks to the patient of duodenal drainage are minimal. (There have been no reports of reactions to the synthetic hormone.) Nevertheless, duodenal drainage is uncomfortable.

A modification of duodenal drainage involves the collection of bile through an endoscope at the time of an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy-either esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) or ERCP.

The oral cholecystogram or OCG is a radiologic (X-ray) procedure for diagnosing gallstones.

The OCG is an excellent procedure for diagnosing gallstones; it finds 95% of them. The OCG has been replaced, however, by ultrasonography because ultrasonography is slightly better at finding gallstones and can be done immediately without waiting one or two days for the iodine to be absorbed, excreted, and concentrated.

Unlike ultrasonography, the OCG also cannot give information about the presence of non-gallstone-related diseases. As would be expected, ultrasonography sometimes finds gallstones that are missed by the OCG. Less frequently, the OCG finds gallstones that are missed by ultrasonography. For this reason, if there is a strong suspicion that gallstones are present but ultrasonography does not show them, it is reasonable to consider doing an OCG; however, EUS has mostly replaced the OCG in this situation. An OCG should not be done in individuals who are allergic to iodine.

The intravenous cholangiogram or IVC is a radiologic (X-ray) procedure that is used primarily for looking at the larger intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts. It can be used to locate gallstones within these ducts.

An iodine-containing dye is injected intravenously into the blood. The dye is removed from the blood by the liver and excreted into the bile. Unlike the iodine used in the OCG, the iodine in the IVC is concentrated sufficiently enough in the bile ducts to outline the ducts and any gallstones within them. The IVC is rarely used because it has been replaced by MRI cholangiography and endoscopic ultrasound. Moreover, occasional serious reactions to the iodine-containing dye can occur, which rarely may result in the death of the patient.

A senior male patient and doctor. Usually, it is not difficult to diagnose gallstones.

A senior male patient and doctor. Usually, it is not difficult to diagnose gallstones. Usually, it is not difficult to diagnose gallstones. Problems arise, however, because of the high prevalence of silent gallstones and the occasional gallstone that is difficult to diagnose.

If a patient has symptoms that are typical for gallstones, for example, biliary colic, cholecystitis, or pancreatitis, and has gallstones on ultrasonography, little else usually needs to be done to demonstrate that the gallstones are causing the symptoms unless the patient has other complicating medical issues.

If symptoms are not typical for gallstones there is a possibility that the gallstones are innocent bystanders (silent), and most importantly, removing the gallbladder surgically will not resolve the patient's problem or prevent further symptoms. In addition, the real cause of the symptoms will not be pursued. In such a situation, there is a need to obtain further evidence, other than their mere presence, that the gallstones are causing the problem. Such evidence can be obtained during an acute episode or shortly thereafter.

If ultrasonography can be done during an acute episode of pain or inflammation caused by gallstones, it may be possible to demonstrate an enlarged gallbladder or bile duct caused by obstruction of the ducts by the gallstone. This is likely to require ultrasonography again after the episode has resolved in order to demonstrate that the gallbladder indeed was larger during the episode than before or after the episode. It is easier to obtain the necessary ultrasonography if the episode lasts several hours, but it is much more difficult to obtain ultrasonography rapidly enough if the episode lasts only 15 minutes.

Another approach is to test the blood for abnormal liver and pancreatic enzymes. The advantage here is that the enzymes, though not always elevated, can be elevated during an acute attack and for several hours after an episode of gallstone-related pain or inflammation, so they may be abnormal even after the episode has subsided. It is important to remember, however, that the enzymes are not specific for gallstones, and it is necessary to exclude other liver and pancreatic causes for abnormal enzymes.

Sometimes, episodes of pain or inflammation may be more or less typical of gallstones, but transabdominal ultrasonography may not demonstrate either gallstones or another cause of the episodes. In this situation, it is necessary to decide whether the suspicion is high or low for gallstones as a cause of the episodes. If suspicion is low because of lack of typical symptoms, it may be reasonable only to repeat the ultrasonography, possibly obtain an OCG, and/or test for abnormalities of liver or pancreatic enzymes. If suspicion is high because of more typical symptoms, it is reasonable to investigate even further with endoscopic ultrasonography, ERCP, and duodenal drainage. Prior to these "invasive" procedures, some physicians recommend MRCP.

X-Ray during laparoscopic cholecystectomy, sphincterotomy and extraction of gallstones, oral dissolution therapy, and extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy are some of the treatments.

X-Ray during laparoscopic cholecystectomy, sphincterotomy and extraction of gallstones, oral dissolution therapy, and extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy are some of the treatments. Most gallstones are silent and do not need treatment.

Cholecystectomy (removal of the gallbladder surgically) is the standard treatment for gallstones in the gallbladder. Surgery may be done through a large abdominal incision, laparoscopically, or robotically through small punctures in the abdominal wall. Laparoscopic surgery results in less pain and a faster recovery. Robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery has 3D visualization. Cholecystectomy has a low rate of complications, but serious complications such as damage to the bile ducts and leakage of bile occasionally occur. There also is risk associated with the general anesthesia that is necessary for either type of surgery. Problems following removal of the gallbladder are few. Digestion of food is not affected, and no change in diet is necessary. Nevertheless, chronic diarrhea occurs in approximately 10% of patients.

Sometimes a gallstone may be stuck in the hepatic or common bile ducts. In such situations, there usually are gallstones in the gallbladder as well, and cholecystectomy is necessary. It may be possible to remove the gallstone stuck in the duct at the time of surgery, but this may not always be possible. An alternative means for removing gallstones in the duct before or after cholecystectomy is with sphincterotomy followed by extraction of the gallstone.

Sphincterotomy involves cutting the muscle of the common bile duct (sphincter of Oddi) at the junction of the common bile duct and the duodenum in order to allow easier access to the common bile duct. The cutting is done with an electrosurgical instrument passed through the same type of endoscope that is used for ERCP. After the sphincter is cut, instruments may be passed through the endoscope and into the hepatic and common bile ducts to grab and pull out the gallstone or to crush the gallstone. It also is possible to pass a lithotripsy instrument that uses high-frequency sound waves to break up the gallstone. Complications of sphincterotomy and extraction of gallstones include risks associated with general anesthesia, perforation of the bile ducts or duodenum, bleeding, and pancreatitis.

It is possible to dissolve some cholesterol gallstones with medication taken orally. The medication is a naturally occurring bile acid called ursodeoxycholic acid or ursodiol (Actigall, Urso). Bile acids are one of the detergents that the liver secretes into bile to dissolve cholesterol. Although one might expect therapy with ursodiol to work by increasing the number of bile acids in bile and thereby cause the cholesterol in gallstones to dissolve, the mechanism of ursodiol's action actually is different. Ursodiol reduces the amount of cholesterol secreted in bile. The bile then has less cholesterol and becomes capable of dissolving the cholesterol in the gallstones.

There are important limitations to the use of ursodiol:

Due to these limitations, ursodiol generally is used only in individuals with smaller gallstones that are likely to have a very high cholesterol content and who are at high risk for surgery because of ill health. It also is reasonable to use ursodiol in individuals whose gallstones were perhaps formed because of a transient event, for example, the rapid loss of weight, since the gallstones would not be expected to recur following successful dissolution. Another use of ursodiol is to prevent the formation of gallstones in patients who will lose weight rapidly.

Extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy (ESWL) is an infrequently used method for treating gallstones, particularly those lodged in bile ducts. ESWL generators produce shock waves outside of the body that is then focused on the gallstone. The shock waves shatter the gallstone, and the resulting pieces of the gallstone either drain into the intestine on their own or are extracted endoscopically. Shock waves also can be used to break up gallstones via special catheters passed through an endoscope at the time of ERCP.

There are no natural or home remedies to treat gallstones.

A doctor examining a gallstone patient. Biliary colic is the most common symptom of gallstones.

A doctor examining a gallstone patient. Biliary colic is the most common symptom of gallstones. Biliary colic is the most common symptom of gallstones, but, fortunately, it is usually a self-limited symptom. There are, however, more serious complications of gallstones.

Cholecystitis means inflammation of the gallbladder. Like biliary colic, it too is caused by sudden obstruction of the ducts, usually the cystic duct by a gallstone. In fact, cholecystitis may begin with an episode of biliary colic. Obstruction of the cystic duct causes the wall of the gallbladder to begin secreting fluid, but for unclear reasons, inflammation sets in. At first, the inflammation is sterile, that is, there is no infection with bacteria; however, over time the bile and gallbladder become infected with bacteria that travel through the bile ducts from the intestine.

With cholecystitis, there is a constant pain in the right upper abdomen. The inflammation extends through the wall of the gallbladder, and the right upper abdomen becomes particularly tender when it is pressed or even tapped. Unlike with biliary colic, however, it is painful to move around. Individuals with cholecystitis usually lie still. There is fever, and the white blood cell count is elevated, both signs of inflammation. Cholecystitis usually is treated with antibiotics, and most episodes will resolve over several days. Even without antibiotics, cholecystitis often resolves. As with biliary colic, movement of the gallstone out of the cystic duct and back into the gallbladder relieves the obstruction and allows the inflammation to resolve.

Cholangitis is a condition in which bile in the common, hepatic, and intrahepatic ducts becomes infected. Like cholecystitis, the infection spreads through the ducts from the intestine after the ducts become obstructed by a gallstone. Patients with cholangitis are very sick with high fever and elevated white blood cell counts. Cholangitis may result in an abscess within the liver or sepsis. (See the discussion of sepsis that follows.)

Gangrene of the gallbladder is a condition in which the inflammation of cholecystitis cuts off the supply of blood to the gallbladder. Without blood, the tissues forming the wall of the gallbladder die, and this makes the wall very weak. The weakness combined with infection often leads to rupture of the gallbladder. The infection then may spread throughout the abdomen, though often the rupture is confined to a small area around the gallbladder (a confined perforation).

Jaundice is a condition in which bilirubin accumulates in the body. Bilirubin is brownish-black in color but is yellow when it is not too concentrated. A build-up of bilirubin in the body turns the skin and whites of the eye (sclera) yellow. Jaundice occurs when there is prolonged obstruction of the bile ducts. The obstruction may be due to gallstones, but it also may be due to many other causes, for example, tumors of the bile ducts or surrounding tissues. (Other causes of jaundice are rapid destruction of red blood cells that overwhelms the ability of the liver to remove bilirubin from the blood or a damaged liver that cannot remove bilirubin from the blood normally.) Jaundice, by itself, generally does not cause problems.

Pancreatitis means inflammation of the pancreas. The two most common causes of pancreatitis are alcoholism and gallstones. The pancreas surrounds the common bile duct as it enters the intestine. The pancreatic duct that drains the digestive juices from the pancreas joins the common bile duct just before it empties into the intestine. If a gallstone obstructs the common bile duct just after the pancreatic duct joins it, the flow of pancreatic juice from the pancreas is blocked. This results in inflammation within the pancreas. Pancreatitis due to gallstones usually is mild, but it may cause serious illness and even death. Fortunately, severe pancreatitis due to gallstones is rare.

Sepsis is a condition in which bacteria from any source within the body, including the gallbladder or bile ducts, enter into the bloodstream and spread throughout the body. Although the bacteria usually remain within the blood, they also may spread to distant tissues and lead to the formation of abscesses (localized areas of infection with formation of pus). Sepsis is a feared complication of any infection. The signs of sepsis include high fever, high white blood cell count, and, less frequently, rigors (shaking chills) or a drop in blood pressure.

A fistula is an abnormal tract through which fluid can flow between two hollow organs or between an abscess and a hollow organ or skin. Gallstones cause fistulas when the hard gallstone erodes through the soft wall of the gallbladder or bile ducts. Most commonly, the gallstone erodes into the small intestine, stomach, or common bile duct. This can leave a tract that allows bile to flow from the gallbladder to the small intestine, stomach, or the common bile duct. If the fistula enters the distal part of the small intestine, the concentrated bile can lead to problems such as diarrhea. Rarely, the gallstone erodes into the abdominal cavity. The bile then leaks into the abdominal cavity and causes inflammation of the lining of the abdomen (peritoneum), a condition called bile peritonitis.

Ileus is a condition in which there is an obstruction to the flow of food, gas, and liquid within the intestine. It may be due to a mechanical obstruction, for example, a tumor within the intestine, or a functional obstruction, for example, inflammation of the intestine or surrounding tissues that prevents the muscles of the intestine from working normally and propelling intestinal contents. If a large gallstone erodes through the wall of the gallbladder and into the stomach or small intestine, it will be propelled through the small intestine. The narrowest part of the small intestine is the ileocecal valve, which is located at the site where the small intestine joins the colon. If the gallstone is too large to pass through the valve, it can obstruct the small intestine and cause an ileus. Gallstones also may cause ileus if there are other abnormal narrowings in the intestine such as a tumor or scarring.

Cancer of the gallbladder usually is associated with gallstones, but it is not clear which comes first, that is, whether the gallstones precede cancer and, therefore, could potentially be the cause of cancer or the gallstones form because cancer is present. Cancer of the gallbladder arises in less than 1% of individuals with gallstones. Therefore, concern about the future development of cancer is by itself not a good reason for removing the gallbladder when gallstones are present.

Longitudinal and axial scans through the gallbladder show layering of sludge (S) in the gallbladder.

Longitudinal and axial scans through the gallbladder show layering of sludge (S) in the gallbladder. Sludge is a common term that is applied to an abnormality of bile that is seen with ultrasonography of the gallbladder. Specifically, the bile within the gallbladder is seen to be of two different densities with the denser bile on the bottom. The bile is denser because it contains microscopic particles, usually cholesterol or pigment, embedded in mucus. (The mucus is secreted by the gallbladder.) Over time, sludge may remain in the gallbladder, it may disappear and not return, or it may come and go. As discussed previously, these particles may be precursors of gallstones, and they occur often in some situations in which gallstones frequently appear, for example, rapid weight loss, pregnancy, and prolonged fasting.

Nevertheless, it appears that sludge goes on to become gallstones in only a minority of individuals. Just to make matters more difficult, it is not clear how often - if at all - sludge alone causes problems. Sludge has been blamed for many of the same symptoms as gallstones-biliary colic, cholecystitis, and pancreatitis, but often these symptoms and complications are caused by very small gallstones that are missed by ultrasonography. Thus, there is some uncertainty about the importance of sludge.

It is clear, however, that sludge is not the equivalent of gallstones. The practical implication of this uncertainty is that unless an individual's symptoms are typical of gallstones, sludge should not be considered as a possible cause of the symptoms.

Ideally, it would be better if gallstones could be prevented rather than treated. Prevention of cholesterol gallstones is feasible since ursodiol, the bile acid medication that dissolves some cholesterol gallstones, also prevents them from forming. The difficulty is to identify individuals who are at a high risk for developing cholesterol gallstones over a relatively short period of time so that the duration of preventive treatment can be limited. One such group is obese individuals losing weight rapidly with very low calorie diets or with surgery. The risk of gallstones in this group is as high as 40% to 60%. In fact, ursodiol has been shown in several studies to be very effective at preventing gallstones in these individuals. It is important to stress that no dietary changes have been shown to treat or prevent gallstones.

A doctor discusses gallstone prevention and possible after-effects of removal with a patient in the hospital. Current scientific studies are directed at uncovering the specific genes that are responsible for gallstones.

A doctor discusses gallstone prevention and possible after-effects of removal with a patient in the hospital. Current scientific studies are directed at uncovering the specific genes that are responsible for gallstones. Gallstones usually are diagnosed by a gastroenterologist, a medical subspecialist who deals with diseases of the intestine, liver, pancreas, and gallbladder. General surgeons also may be involved in the diagnosis of gallstones but usually are the doctors who treat gallstones because the common treatment is surgical removal of the gallbladder.

It is clear that genetic factors are important in determining who develops gallstones. Current scientific studies are directed at uncovering the specific genes that are responsible for gallstones. To date, 8-10 genes have been identified as being associated with cholesterol gallstones, at least in animals that develop cholesterol gallstones. Not surprisingly, the products of many of these genes control the production and secretion (by the liver) of cholesterol, bile acids, and lecithin. The long-term goal is to be able to identify individuals who are genetically at very high risk for cholesterol gallstones and to offer them preventive treatment. An understanding of the exact mechanism(s) of gallstone formation also may result in new therapies for treatment and prevention.

Surgery for gallstones has undergone a major transition from requiring large abdominal incisions to requiring only tiny incisions for laparoscopic instruments (laparoscopic cholecystectomy). It is possible that there will be another transition. Surgeons are experimenting with a technique called natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES). NOTES is a new technique for accomplishing standard intra-abdominal surgery, but access to the abdomen is through a natural orifice - the mouth, anus, or vagina.

For NOTES , a flexible endoscopic instrument is similar to the flexible endoscopes presently being used widely is introduced through the chosen orifice, through an incision somewhere inside the orifice (for example, the stomach), and into the abdominal cavity. Thus, the only incision is within the body and not visible on the body's surface. There are potential advantages to this type of surgery, but it is in the early stages of development, and it is unclear what the future role of NOTES will be in gallbladder surgery. Nevertheless, several series of patients have already been described who have had their gallbladders removed via NOTES primarily through the vagina.

Six conseils d'experts pour améliorer votre digestion gratuitement

Six conseils d'experts pour améliorer votre digestion gratuitement

Liens de recherche prévalence du SRAS-CoV-2,

Liens de recherche prévalence du SRAS-CoV-2,

Lorsque la douleur à l'estomac est et n'est pas une urgence

Lorsque la douleur à l'estomac est et n'est pas une urgence

Torsions des organes abdominaux – Diagnostic de l'abdomen aigu

Torsions des organes abdominaux – Diagnostic de l'abdomen aigu

Les diététiciens comme ambassadeurs de la santé intestinale

Les diététiciens comme ambassadeurs de la santé intestinale

L'exercice et ses effets sur la santé et le microbiome intestinal

L'exercice et ses effets sur la santé et le microbiome intestinal

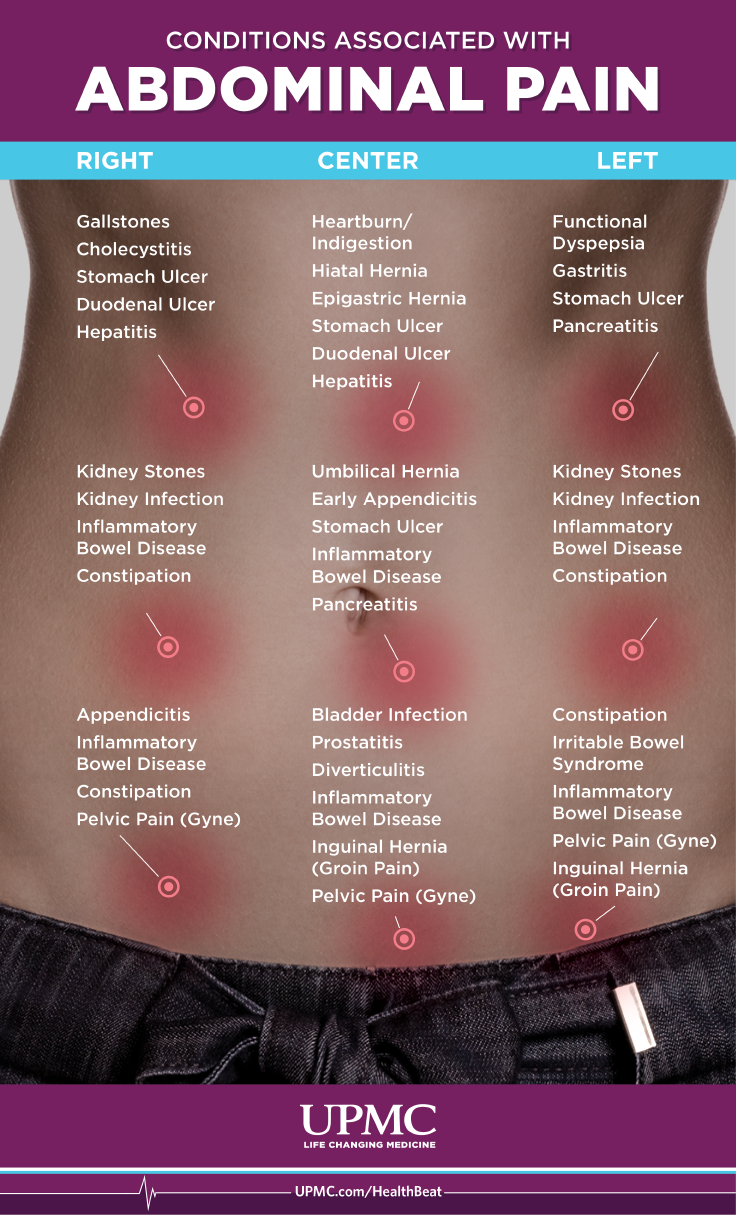

Douleur d'estomac :quand s'inquiéter d'une douleur d'estomac

Tout le monde a des maux destomac - ou des douleurs abdominales - de temps en temps. Habituellement, les douleurs à lestomac sont des affections inoffensives causées par une suralimentation, des gaz o

Douleur d'estomac :quand s'inquiéter d'une douleur d'estomac

Tout le monde a des maux destomac - ou des douleurs abdominales - de temps en temps. Habituellement, les douleurs à lestomac sont des affections inoffensives causées par une suralimentation, des gaz o

Les causes de la douleur abdominale

Quest-ce qui cause la douleur abdominale ? La douleur abdominale est une douleur ou un inconfort quune personne ressent nimporte où entre le bas de la poitrine et laine distale. Certains professionne

Les causes de la douleur abdominale

Quest-ce qui cause la douleur abdominale ? La douleur abdominale est une douleur ou un inconfort quune personne ressent nimporte où entre le bas de la poitrine et laine distale. Certains professionne

Cancer du foie (carcinome hépatocellulaire)

Faits sur le cancer du foie Le cancer du foie est souvent le résultat dune maladie chronique du foie. La plupart des personnes atteintes dun cancer du foie (cancer du foie) le contractent dans le cad

Cancer du foie (carcinome hépatocellulaire)

Faits sur le cancer du foie Le cancer du foie est souvent le résultat dune maladie chronique du foie. La plupart des personnes atteintes dun cancer du foie (cancer du foie) le contractent dans le cad