Ein männlicher Erwachsener, der auf den Umriss einer Leber zeigt und eine Gallenblase auf seinen Bauch malt.

Ein männlicher Erwachsener, der auf den Umriss einer Leber zeigt und eine Gallenblase auf seinen Bauch malt. Zu den Symptomen eines Gallenblasenanfalls gehören:

Illustration des Verdauungssystems mit Gallensteinen und Nahaufnahme von Gallensteinen in der Gallenblase ein Stein, der auch in die Gallenblase gelangt ist Ductus cysticus.

Illustration des Verdauungssystems mit Gallensteinen und Nahaufnahme von Gallensteinen in der Gallenblase ein Stein, der auch in die Gallenblase gelangt ist Ductus cysticus. Gallensteine (oft fälschlicherweise als Gallensteine bezeichnet) sind Steine, die sich in der Galle (Galle) innerhalb der Gallenblase bilden. (Die Gallenblase ist ein birnenförmiges Organ direkt unterhalb der Leber, das die von der Leber abgesonderte Galle speichert.) Gallensteine erreichen eine Größe zwischen einem Sechzehntel Zoll und mehreren Zoll.

Aus dem Gallengang kann die Galle aus zwei verschiedenen Richtungen fließen.

Einmal in der Gallenblase angekommen, wird die Galle durch die Entfernung (Absorption) von Wasser konzentriert. Während einer Mahlzeit zieht sich der Muskel, der die Wand der Gallenblase bildet, zusammen und drückt die konzentrierte Galle in der Gallenblase zurück durch den Gallengang in den gemeinsamen Gallengang und dann in den Darm. (Konzentrierte Galle ist viel effektiver für die Verdauung als die unkonzentrierte Galle, die von der Leber direkt in den Darm gelangt.) Der Zeitpunkt der Kontraktion der Gallenblase – während einer Mahlzeit – ermöglicht es der konzentrierten Galle aus der Gallenblase, sich mit der Nahrung zu vermischen. P>

Gallensteine bilden sich normalerweise in der Gallenblase; Sie können sich jedoch auch überall dort bilden, wo Galle vorhanden ist – in den intrahepatischen, hepatischen, gemeinsamen Gallen- und Zystengängen.

Gallensteine können sich auch in der Galle bewegen, beispielsweise von der Gallenblase in die Zystik oder den gemeinsamen Gang.

Ein Mann leidet unter Gallenkoliken. Das häufigste Symptom von Gallensteinen ist die Gallenkolik.

Ein Mann leidet unter Gallenkoliken. Das häufigste Symptom von Gallensteinen ist die Gallenkolik. Die Mehrheit der Menschen mit Gallensteinen hat keine Anzeichen oder Symptome und ist sich ihrer Gallensteine nicht bewusst. (Die Gallensteine sind „stumm“.) Diese Gallensteine werden häufig als Ergebnis von Tests (z. B. Ultraschall oder Röntgenaufnahmen des Abdomens) gefunden, die bei der Beurteilung anderer Erkrankungen als Gallensteine durchgeführt werden. Symptome können später im Leben auftreten, jedoch nach vielen Jahren ohne Symptome. Somit entwickeln über einen Zeitraum von fünf Jahren etwa 10 % der Menschen mit stillen Gallensteinen Symptome. Sobald sich Symptome entwickeln, werden sie wahrscheinlich andauern und sich oft verschlimmern.

Wenn Anzeichen und Symptome von Gallensteinen auftreten, treten sie praktisch immer auf, weil die Gallensteine die Gallenwege verstopfen.

Das häufigste Symptom von Gallensteinen ist eine Gallenkolik. Gallenkolik ist eine sehr spezifische Art von Schmerzen, die bei 80 % der Menschen mit Gallensteinen, die Symptome entwickeln, als primäres oder einziges Symptom auftritt. Eine Gallenkolik tritt auf, wenn die Gallenwege (Zystengang, Lebergang oder Hauptgallengang) plötzlich durch einen Gallenstein blockiert werden. Eine langsam fortschreitende Obstruktion, wie bei einem Tumor, verursacht keine Gallenkoliken. Hinter der Obstruktion sammelt sich Flüssigkeit an und dehnt die Gänge und die Gallenblase aus. Im Falle einer Obstruktion des Lebergangs oder des Hauptgallengangs ist dies auf eine fortgesetzte Sekretion von Galle durch die Leber zurückzuführen. Bei einer Obstruktion des Ductus cysticus sondert die Wand der Gallenblase Flüssigkeit in die Gallenblase ab. Die Ausdehnung der Gänge oder der Gallenblase verursacht Gallenkoliken.

Typischerweise tritt eine Gallenkolik plötzlich auf oder baut sich innerhalb weniger Minuten schnell zu einem Höhepunkt auf.

Gallenkolik ist ein wiederkehrendes Symptom. Sobald die erste Episode auftritt, gibt es wahrscheinlich weitere Episoden. Darüber hinaus gibt es bei jedem Individuum ein Rezidivmuster, d. h. bei einigen Individuen bleiben die Episoden häufig, während sie bei anderen selten sind. Die Mehrheit der Menschen, die eine Gallenkolik entwickeln, entwickelt keine Cholezystitis oder andere Komplikationen. Es gibt ein Missverständnis, dass die Kontraktion der Gallenblase die Ursache für die Verstopfung der Gänge und die Gallenkolik ist. Essen, auch fetthaltige Speisen, verursacht keine Gallenkoliken; Die meisten Episoden von Gallenkoliken treten während der Nacht auf, lange nachdem sich die Gallenblase geleert hat.

Gallensteine werden für viele Symptome verantwortlich gemacht, die sie nicht verursachen. Unter den Symptomen, die Gallensteine nicht verursachen sind:

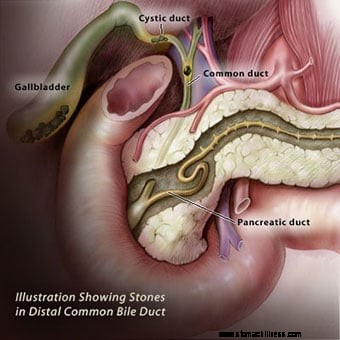

Darstellung von Gallensteinen in der Gallenblase sowie im distalen Choledochus. Der Ductus choledochus hat eine muskulöse Wand.

Darstellung von Gallensteinen in der Gallenblase sowie im distalen Choledochus. Der Ductus choledochus hat eine muskulöse Wand. Die Entfernung der Gallenblase (Cholezystektomie) sollte alle gallensteinbedingten Symptome beseitigen, außer in drei Situationen:

Die Möglichkeit von Gallensteinen in den Gängen kann mit MRCP, endoskopischem Ultraschall und ERCP verfolgt werden. In seltenen Fällen können gallensteinähnliche Symptome durch eine Störung verursacht werden, die als Sphinkter-Oddi-Dysfunktion bezeichnet wird und unten beschrieben wird.

Der Ductus choledochus hat eine muskulöse Wand. Die letzten paar Zentimeter des Muskels des Ductus choledochus, unmittelbar bevor der Ductus in den Zwölffingerdarm mündet, bilden den Schließmuskel von Oddi. Der Schließmuskel von Oddi steuert den Gallenfluss. Da der Pankreasgang meist kurz vor Eintritt in den Zwölffingerdarm in den Ductus choledochus mündet, steuert der Schließmuskel auch den Flüssigkeitsfluss aus dem Pankreasgang. Wenn sich der Muskel des Schließmuskels anspannt, unterbricht er den Fluss von Galle und Bauchspeicheldrüsenflüssigkeit. Wenn es sich entspannt, fließen zum Beispiel nach einer Mahlzeit wieder Galle und Bauchspeicheldrüsenflüssigkeit in den Zwölffingerdarm. Der Schließmuskel kann vernarbt werden und der Gang wird durch die Vernarbung verengt. (Die Ursache der Narbenbildung ist unbekannt.) Der Schließmuskel kann auch zeitweise verkrampfen. In beiden Fällen kann der Fluss von Galle und Bauchspeicheldrüsenflüssigkeit zeitweise abrupt stoppen, was die Auswirkungen eines Gallensteins nachahmt, der Gallenkoliken und Pankreatitis verursacht.

Die Diagnose einer Sphinkter-Oddi-Dysfunktion kann schwierig sein. Der beste diagnostische Test erfordert ein endoskopisches Verfahren mit dem gleichen Endoskoptyp wie die ERCP. Anstatt die Gänge mit Farbstoff zu füllen, wird jedoch der Druck im Schließmuskel gemessen. Wenn der Druck ungewöhnlich hoch ist, sind Vernarbungen oder Krämpfe des Schließmuskels wahrscheinlich. Die Behandlung der Schließmuskel-Oddi-Dysfunktion ist die Sphinkterotomie (zuvor beschrieben). Die Messung von Leber- und Pankreasenzymen im Blut kann auch bei der Diagnose einer Schließmuskelfunktionsstörung hilfreich sein.

Sammlung von Gallensteinen in verschiedenen Größen und Formen.

Sammlung von Gallensteinen in verschiedenen Größen und Formen. Gallensteine können zwischen einem und Hunderten liegen und in der Größe von einem Millimeter bis zu vier oder fünf Zentimetern variieren. Wenn es einzelne oder nur wenige Gallensteine gibt, neigen sie dazu, rund zu sein. Wenn eine größere Anzahl von Gallensteinen vorhanden ist, neigen sie dazu, aufgrund der Reibung eines Gallensteins an einem anderen facettiert zu sein. Gallensteine mit braunem Pigment können krümelig und unregelmäßig sein.

Gallensteine können aus der Gallenblase oder den Gallengängen austreten, besonders wenn sie klein sind. Es ist der Durchgang von Gallensteinen, der zu vielen ihrer Komplikationen führt.

Gallensteine sind häufig; Sie treten bei etwa 20 % der Frauen in den USA, Kanada und Europa auf, aber es gibt große Unterschiede in der Prävalenz zwischen verschiedenen ethnischen Gruppen. Beispielsweise treten Gallensteine 1 ½ bis 2 Mal häufiger bei Skandinaviern und Mexikanern auf. Bei amerikanischen Indianern beträgt die Prävalenz von Gallensteinen mehr als 80 %. Diese Unterschiede sind wahrscheinlich auf genetische (erbliche) Faktoren zurückzuführen. Bei Verwandten ersten Grades (Eltern, Geschwister und Kinder) von Personen mit Gallensteinen ist die Wahrscheinlichkeit, Gallensteine zu haben, 1 ½-mal höher, als wenn sie keinen Verwandten ersten Grades mit Gallensteinen haben. Weitere Unterstützung für eine genetische Veranlagung kommt aus Zwillingsstudien. So haben bei zweieiigen Zwillingspaaren (die 50 % ihrer Gene miteinander teilen) beide Individuen eines Paares in 8 % der Fälle Gallensteine. Bei eineiigen Zwillingspaaren (die 100 % ihrer Gene miteinander teilen) haben beide Individuen in 23 % der Fälle Gallensteine.

Mehrere Zustände sind mit der Bildung von Gallensteinen verbunden, und die Art und Weise, wie sie Gallensteine verursachen, kann variieren. (Siehe Risiken von Gallensteinen.)

Cholesterin-Gallensteine bestehen hauptsächlich aus Cholesterin. Es gibt zwei weitere Prozesse, die die Bildung von Cholesterin-Gallensteinen fördern

Cholesterin-Gallensteine bestehen hauptsächlich aus Cholesterin. Es gibt zwei weitere Prozesse, die die Bildung von Cholesterin-Gallensteinen fördern Es gibt verschiedene Arten von Gallensteinen und jede Art hat eine andere Ursache.

Cholesterin-Gallensteine bestehen hauptsächlich aus Cholesterin. Sie sind die häufigste Art von Gallensteinen und machen 80 % der Gallensteine bei Menschen in Europa und Amerika aus. Cholesterin ist eine der Substanzen (Chemikalien), die Leberzellen in die Galle absondern. Die Sekretion von Cholesterin in die Galle ist ein wichtiger Mechanismus, durch den die Leber überschüssiges Cholesterin aus dem Körper eliminiert.

Damit die Galle Cholesterin transportieren kann, muss das Cholesterin in der Galle gelöst werden. Cholesterin ist jedoch Fett und Galle ist eine wässrige oder wässrige Lösung; Fette lösen sich nicht in wässrigen Lösungen. Damit sich das Cholesterin in der Galle auflöst, sondert die Leber auch zwei Detergenzien, Gallensäuren und Lecithin, in die Galle ab. Diese Reinigungsmittel lösen, genau wie Geschirrspülmittel, das Fettcholesterin auf, damit es mit der Galle durch die Gänge transportiert werden kann. Wenn die Leber zu viel Cholesterin für die Menge an Gallensäuren und Lecithin absondert, die sie absondert, bleibt ein Teil des Cholesterins nicht gelöst. Ebenso bleibt ein Teil des Cholesterins nicht gelöst, wenn die Leber nicht genügend Gallensäuren und Lecithin absondert. In beiden Fällen klebt das ungelöste Cholesterin zusammen und bildet Cholesterinpartikel, die an Größe zunehmen und schließlich zu Gallensteinen werden.

Zwei weitere Prozesse fördern die Bildung von Cholesterin-Gallensteinen, obwohl keiner der Prozesse die Bildung von Cholesterin-Gallensteinen verursachen kann.

Pigmentgallensteine sind die zweithäufigste Art von Gallensteinen.

Pigmentgallensteine sind die zweithäufigste Art von Gallensteinen. Pigmentgallensteine sind die zweithäufigste Art von Gallensteinen. Obwohl Pigmentgallensteine nur 15 % der Gallensteine bei Personen aus Europa und Amerika ausmachen, sind sie in Südostasien häufiger als Cholesterin-Gallensteine. Es gibt zwei Arten von Pigmentgallensteinen:1) schwarze Pigmentgallensteine und 2) braune Pigmentgallensteine.

Das Pigment ist ein Abfallprodukt, das aus Hämoglobin gebildet wird, der sauerstofftragenden Chemikalie in roten Blutkörperchen. Das Hämoglobin aus alten roten Blutkörperchen, die zerstört werden, wird in eine Chemikalie namens Bilirubin umgewandelt und ins Blut freigesetzt. Bilirubin wird von der Leber aus dem Blut entfernt. Die Leber modifiziert das Bilirubin und sondert das modifizierte Bilirubin in die Galle ab, damit es aus dem Körper ausgeschieden werden kann.

Gallensteine mit schwarzem Pigment: Wenn zu viel Bilirubin in der Galle vorhanden ist, verbindet sich das Bilirubin mit anderen Bestandteilen der Galle, z. B. Kalzium, zu einem Pigment (so genannt, weil es dunkelbraun ist). Pigment löst sich schlecht in der Galle und klebt wie Cholesterin zusammen und bildet Partikel, die an Größe zunehmen und schließlich zu Gallensteinen werden. Die Pigmentgallensteine, die sich auf diese Weise bilden, werden schwarze Pigmentgallensteine genannt, weil sie schwarz und hart sind.

Braune Pigmentgallensteine: Bei verminderter Kontraktion der Gallenblase oder Behinderung des Gallenflusses durch die Gänge können Bakterien aus dem Zwölffingerdarm in die Gallengänge und die Gallenblase aufsteigen. Die Bakterien verändern das Bilirubin in den Gängen und der Gallenblase, und das veränderte Bilirubin verbindet sich dann mit Kalzium, um Pigment zu bilden. Das Pigment verbindet sich dann mit Fetten in der Galle (Cholesterin und Fettsäuren aus Lecithin) zu Partikeln, die zu Gallensteinen heranwachsen. Diese Art von Gallenstein wird als brauner Pigmentgallenstein bezeichnet, da er eher braun als schwarz ist. Es ist auch weicher als Gallensteine mit schwarzem Pigment.

Andere Arten von Gallensteinen. Andere Arten von Gallensteinen sind selten. Der vielleicht interessanteste Typ ist der Gallenstein, der sich bei Patienten bildet, die das Antibiotikum Ceftriaxon (Rocephin) einnehmen. Ceftriaxon ist insofern ungewöhnlich, als es in hohen Konzentrationen mit der Galle aus dem Körper ausgeschieden wird. Es verbindet sich mit Kalzium in der Galle und wird unlöslich. Wie Cholesterin und Farbstoff bilden das unlösliche Ceftriaxon und Calcium Partikel, die zu Gallensteinen heranwachsen. Glücklicherweise verschwinden die meisten dieser Gallensteine, sobald das Antibiotikum abgesetzt wird; Sie können jedoch immer noch Probleme verursachen, bis sie verschwinden. Eine andere seltene Art von Gallensteinen wird aus Kalziumkarbonat gebildet.

The eight risk factors for developing cholesterol gallstones include gender, age, obesity, pregnancy, birth control pills and hormone therapy, rapid weight loss, Crohn's disease, and increased blood triglycerides.

The eight risk factors for developing cholesterol gallstones include gender, age, obesity, pregnancy, birth control pills and hormone therapy, rapid weight loss, Crohn's disease, and increased blood triglycerides. There is no relationship between cholesterol in the blood and cholesterol gallstones. Individuals with elevated blood cholesterol do not have an increased prevalence of cholesterol gallstones. A common misconception is that diet is responsible for the development of cholesterol gallstones, however, it isn't. The eight risk factors for developing cholesterol gallstones include:

A female doctor sits next to an ultrasound machine.

A female doctor sits next to an ultrasound machine. Gallstones are diagnosed in one of two situations.

Ultrasonography is the most important means of diagnosing gallstones. Standard computerized tomography (CT or CAT scan) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may occasionally demonstrate gallstones; however, they are not as useful compared to ultrasonography because they miss gallstones.

Ultrasonography is a radiological technique that uses high-frequency sound waves to produce images of the organs and structures of the body. The sound waves are emitted from a device called a transducer and are sent through the body's tissues. The sound waves are reflected by the surfaces and interiors of internal organs and structures as "echoes." These echoes return to the transducer and are transmitted onto a viewing monitor. On the monitor, the outline of organs and structures can be determined as well as their consistency, for example, liquid or solid.

Two types of ultrasonographic techniques can be used for diagnosing gallstones:transabdominal ultrasonography and endoscopic ultrasonography.

For transabdominal ultrasonography, the transducer is placed directly on the skin of the abdomen. The sound waves travel through the skin and then into the abdominal organs. Transabdominal ultrasonography is painless, inexpensive, and without risk to the patient. In addition to identifying 97% of gallstones in the gallbladder, abdominal ultrasonography can identify many other abnormalities related to gallstones. It can identify:

Transabdominal ultrasonography also may identify diseases not related to gallstones that may be the cause of the patient's problem, for example, appendicitis. The limitations of transabdominal ultrasonography are that it can only identify gallstones larger than 4-5 millimeters in size, and it is poor at identifying gallstones in the bile ducts.

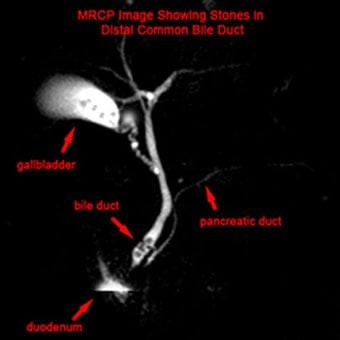

MRCP image showing stones in the common bile duct:(a) Gallbladder with stones (b) Stone in bile duct (c) Pancreatic duct (d) Duodenum.

MRCP image showing stones in the common bile duct:(a) Gallbladder with stones (b) Stone in bile duct (c) Pancreatic duct (d) Duodenum. For endoscopic ultrasonography, a long flexible tube - the endoscope - is swallowed by the patient after he or she has been sedated with intravenous medication. The tip of the endoscope is fitted with an ultrasound transducer. The transducer is advanced into the duodenum where ultrasonographic images are obtained.

Endoscopic ultrasonography can identify gallstones and the same abnormalities as transabdominal ultrasonography; however, since the transducer is much closer to the structures of interest - the gallbladder, bile ducts, and pancreas - better images are obtained than with transabdominal ultrasonography. Thus, it is possible to visualize smaller gallstones with EUS than transabdominal ultrasonography. EUS also is better at identifying gallstones in the common bile duct.

Although endoscopic ultrasonography is in many ways better than transabdominal ultrasonography, it is expensive, not available everywhere, and carries a small risk of complications such as those associated with the use of intravenous sedation, and intestinal perforation by the endoscope. Fortunately, transabdominal ultrasonography usually gives most of the necessary information, and endoscopic ultrasonography is needed only infrequently. Endoscopic ultrasonography also is a better way than transabdominal ultrasonography to evaluate the pancreas for pancreatitis or its complications.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography or MRCP is a modification of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) that allows the bile and pancreatic ducts to be examined.

The procedure is called cholangitis (referring to the bile ducts) pancreatography (referring to the pancreatic duct) because it can demonstrate the bile and pancreatic ducts.

MRCP has in many instances replaced other procedures such as cholescintigraphy (HIDA scan) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for evaluating the bile ducts. It can identify gallstones in the bile ducts, obstruction of the ducts, and leaks of bile. There are no risks to the patient with MRCP except for very rare reactions to the injected dye.

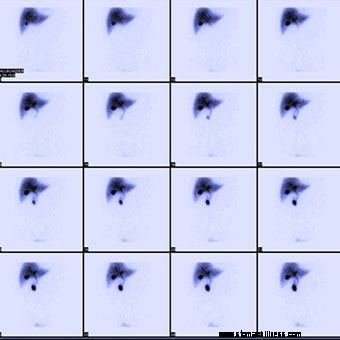

Normal hepatobiliary scan (HIDA scan) showing a series of scans done over time to see where bile is excreted and/or accumulated.

Normal hepatobiliary scan (HIDA scan) showing a series of scans done over time to see where bile is excreted and/or accumulated. Cholescintigraphy is a procedure done by nuclear medicine physicians. It also is referred to as a HIDA scan or a gallbladder scan.

HIDA scans are used to identify obstruction of the bile ducts, for example, by a gallstone. They also may identify bile leaks and fistulas. There are no risks to the patient with HIDA scans.

Cholescintigraphy also is used to study the emptying of the gallbladder. Some patients with gallstones have had gallbladder inflammation due to recognized or unrecognized episodes of cholecystitis. (There also are uncommon, non-gallstone-related causes of inflammation of the gallbladder.) The inflammation can result in scarring of the gallbladder's wall and muscle, which reduces the ability of the gallbladder to contract. As a result, the gallbladder does not empty normally. During cholescintigraphy, a synthetic hormone related to cholecystokinin (the hormone the body produces and releases during a meal to cause the gallbladder to contract) can be injected intravenously to cause the gallbladder to contract and squeeze out its bile and radioactivity into the intestine. If the gallbladder does not empty the bile and radioactivity normally, it is assumed that the gallbladder is diseased due to gallstones or non-gallstone-related inflammation.

The problem with interpreting a gallbladder emptying study is that many people with normal gallbladders have abnormal emptying of the gallbladder. Therefore, it is hazardous to base a diagnosis of a diseased gallbladder on abnormal gallbladder emptying alone.

The doctor performs an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) on a woman for gallstones.

The doctor performs an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) on a woman for gallstones. ERCP is a combined endoscope and X-ray procedure performed to examine the duodenum (the first portion of the small intestine), the papilla of Vater (a small nipple-like structure where the common bile and pancreatic ducts enter the duodenum), the gallbladder, and bile and pancreatic ducts.

The procedure is performed by using a long, flexible, side-viewing instrument (a duodenoscope, a type of endoscope) about the diameter of a fountain pen. The duodenoscope is flexible and can be directed and moved around the many bends of the stomach and intestine. The video-endoscope is the most common type of duodenoscope and uses a chip at the tip of the instrument to transmit video images to a TV screen.

ERCP can identify; 1) gallstones in the gallbladder (though it is not particularly good at this) and 2) blockage of the bile ducts, for example, by gallstones, and 3) bile leaks. ERCP also may identify diseases not related to gallstones that may be the cause of the patient's problem, for example, pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer.

An important advantage of ERCP is that instruments can be passed through the same channel as the cannula used to inject the dye to extract gallstones stuck in the common and hepatic ducts. This can save the patient from having an operation. ERCP has several risks associated with it, including the drugs used for sedation, perforation of the duodenum by the duodenoscope, and pancreatitis (due to damage to the pancreas). If gallstones are extracted, bleeding also may occur as a complication.

A doctor holding an anatomical model of the human liver and pointing to a gallstone.

A doctor holding an anatomical model of the human liver and pointing to a gallstone. When the liver or pancreas becomes inflamed or their ducts become obstructed and enlarged, the cells of the liver and pancreas release some of their enzymes into the blood. The most commonly measured liver enzymes in blood are aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT). The most commonly-measured pancreatic enzymes in blood are amylase and lipase. Many medical conditions that affect the liver or pancreas cause these blood tests to become abnormal, so these abnormalities alone cannot be used to diagnose gallstones. Nevertheless, abnormalities of these tests suggest there is a problem with the liver, bile ducts, or pancreas, and gallstones are a common cause of such abnormal tests, particularly during sudden obstruction of the bile ducts or pancreatic ducts. Thus, abnormal liver and pancreatic blood test direct attention to the possibility that gallstones may be causing the acute problem.

Duodenal biliary drainage is a procedure that occasionally can be useful in diagnosing gallstones; however, it is not often used. As previously discussed, gallstones begin as microscopic particles of cholesterol or pigment that grow in size. It is clear that some people who develop biliary colic, cholecystitis, or pancreatitis have only these particles in their gallbladders, yet the particles are too small to obstruct the ducts. There are two potential explanations for how obstruction might occur in this situation. The first is that a small gallstone initially caused an obstruction before passing through the bile ducts into the intestine. The second is that particles passing through the bile ducts can "irritate" the ducts, causing spasm of the muscle within the walls of the ducts (which obstructs the flow of bile) or inflammation of the duct that causes the wall of the duct to swell (which also obstructs the duct).

The risks to the patient of duodenal drainage are minimal. (There have been no reports of reactions to the synthetic hormone.) Nevertheless, duodenal drainage is uncomfortable.

A modification of duodenal drainage involves the collection of bile through an endoscope at the time of an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy-either esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) or ERCP.

The oral cholecystogram or OCG is a radiologic (X-ray) procedure for diagnosing gallstones.

The OCG is an excellent procedure for diagnosing gallstones; it finds 95% of them. The OCG has been replaced, however, by ultrasonography because ultrasonography is slightly better at finding gallstones and can be done immediately without waiting one or two days for the iodine to be absorbed, excreted, and concentrated.

Unlike ultrasonography, the OCG also cannot give information about the presence of non-gallstone-related diseases. As would be expected, ultrasonography sometimes finds gallstones that are missed by the OCG. Less frequently, the OCG finds gallstones that are missed by ultrasonography. For this reason, if there is a strong suspicion that gallstones are present but ultrasonography does not show them, it is reasonable to consider doing an OCG; however, EUS has mostly replaced the OCG in this situation. An OCG should not be done in individuals who are allergic to iodine.

The intravenous cholangiogram or IVC is a radiologic (X-ray) procedure that is used primarily for looking at the larger intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts. It can be used to locate gallstones within these ducts.

An iodine-containing dye is injected intravenously into the blood. The dye is removed from the blood by the liver and excreted into the bile. Unlike the iodine used in the OCG, the iodine in the IVC is concentrated sufficiently enough in the bile ducts to outline the ducts and any gallstones within them. The IVC is rarely used because it has been replaced by MRI cholangiography and endoscopic ultrasound. Moreover, occasional serious reactions to the iodine-containing dye can occur, which rarely may result in the death of the patient.

A senior male patient and doctor. Usually, it is not difficult to diagnose gallstones.

A senior male patient and doctor. Usually, it is not difficult to diagnose gallstones. Usually, it is not difficult to diagnose gallstones. Problems arise, however, because of the high prevalence of silent gallstones and the occasional gallstone that is difficult to diagnose.

If a patient has symptoms that are typical for gallstones, for example, biliary colic, cholecystitis, or pancreatitis, and has gallstones on ultrasonography, little else usually needs to be done to demonstrate that the gallstones are causing the symptoms unless the patient has other complicating medical issues.

If symptoms are not typical for gallstones there is a possibility that the gallstones are innocent bystanders (silent), and most importantly, removing the gallbladder surgically will not resolve the patient's problem or prevent further symptoms. In addition, the real cause of the symptoms will not be pursued. In such a situation, there is a need to obtain further evidence, other than their mere presence, that the gallstones are causing the problem. Such evidence can be obtained during an acute episode or shortly thereafter.

If ultrasonography can be done during an acute episode of pain or inflammation caused by gallstones, it may be possible to demonstrate an enlarged gallbladder or bile duct caused by obstruction of the ducts by the gallstone. This is likely to require ultrasonography again after the episode has resolved in order to demonstrate that the gallbladder indeed was larger during the episode than before or after the episode. It is easier to obtain the necessary ultrasonography if the episode lasts several hours, but it is much more difficult to obtain ultrasonography rapidly enough if the episode lasts only 15 minutes.

Another approach is to test the blood for abnormal liver and pancreatic enzymes. The advantage here is that the enzymes, though not always elevated, can be elevated during an acute attack and for several hours after an episode of gallstone-related pain or inflammation, so they may be abnormal even after the episode has subsided. It is important to remember, however, that the enzymes are not specific for gallstones, and it is necessary to exclude other liver and pancreatic causes for abnormal enzymes.

Sometimes, episodes of pain or inflammation may be more or less typical of gallstones, but transabdominal ultrasonography may not demonstrate either gallstones or another cause of the episodes. In this situation, it is necessary to decide whether the suspicion is high or low for gallstones as a cause of the episodes. If suspicion is low because of lack of typical symptoms, it may be reasonable only to repeat the ultrasonography, possibly obtain an OCG, and/or test for abnormalities of liver or pancreatic enzymes. If suspicion is high because of more typical symptoms, it is reasonable to investigate even further with endoscopic ultrasonography, ERCP, and duodenal drainage. Prior to these "invasive" procedures, some physicians recommend MRCP.

X-Ray during laparoscopic cholecystectomy, sphincterotomy and extraction of gallstones, oral dissolution therapy, and extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy are some of the treatments.

X-Ray during laparoscopic cholecystectomy, sphincterotomy and extraction of gallstones, oral dissolution therapy, and extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy are some of the treatments. Most gallstones are silent and do not need treatment.

Cholecystectomy (removal of the gallbladder surgically) is the standard treatment for gallstones in the gallbladder. Surgery may be done through a large abdominal incision, laparoscopically, or robotically through small punctures in the abdominal wall. Laparoscopic surgery results in less pain and a faster recovery. Robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery has 3D visualization. Cholecystectomy has a low rate of complications, but serious complications such as damage to the bile ducts and leakage of bile occasionally occur. There also is risk associated with the general anesthesia that is necessary for either type of surgery. Problems following removal of the gallbladder are few. Digestion of food is not affected, and no change in diet is necessary. Nevertheless, chronic diarrhea occurs in approximately 10% of patients.

Sometimes a gallstone may be stuck in the hepatic or common bile ducts. In such situations, there usually are gallstones in the gallbladder as well, and cholecystectomy is necessary. It may be possible to remove the gallstone stuck in the duct at the time of surgery, but this may not always be possible. An alternative means for removing gallstones in the duct before or after cholecystectomy is with sphincterotomy followed by extraction of the gallstone.

Sphincterotomy involves cutting the muscle of the common bile duct (sphincter of Oddi) at the junction of the common bile duct and the duodenum in order to allow easier access to the common bile duct. The cutting is done with an electrosurgical instrument passed through the same type of endoscope that is used for ERCP. After the sphincter is cut, instruments may be passed through the endoscope and into the hepatic and common bile ducts to grab and pull out the gallstone or to crush the gallstone. It also is possible to pass a lithotripsy instrument that uses high-frequency sound waves to break up the gallstone. Complications of sphincterotomy and extraction of gallstones include risks associated with general anesthesia, perforation of the bile ducts or duodenum, bleeding, and pancreatitis.

It is possible to dissolve some cholesterol gallstones with medication taken orally. The medication is a naturally occurring bile acid called ursodeoxycholic acid or ursodiol (Actigall, Urso). Bile acids are one of the detergents that the liver secretes into bile to dissolve cholesterol. Although one might expect therapy with ursodiol to work by increasing the number of bile acids in bile and thereby cause the cholesterol in gallstones to dissolve, the mechanism of ursodiol's action actually is different. Ursodiol reduces the amount of cholesterol secreted in bile. The bile then has less cholesterol and becomes capable of dissolving the cholesterol in the gallstones.

There are important limitations to the use of ursodiol:

Due to these limitations, ursodiol generally is used only in individuals with smaller gallstones that are likely to have a very high cholesterol content and who are at high risk for surgery because of ill health. It also is reasonable to use ursodiol in individuals whose gallstones were perhaps formed because of a transient event, for example, the rapid loss of weight, since the gallstones would not be expected to recur following successful dissolution. Another use of ursodiol is to prevent the formation of gallstones in patients who will lose weight rapidly.

Extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy (ESWL) is an infrequently used method for treating gallstones, particularly those lodged in bile ducts. ESWL generators produce shock waves outside of the body that is then focused on the gallstone. The shock waves shatter the gallstone, and the resulting pieces of the gallstone either drain into the intestine on their own or are extracted endoscopically. Shock waves also can be used to break up gallstones via special catheters passed through an endoscope at the time of ERCP.

There are no natural or home remedies to treat gallstones.

A doctor examining a gallstone patient. Biliary colic is the most common symptom of gallstones.

A doctor examining a gallstone patient. Biliary colic is the most common symptom of gallstones. Biliary colic is the most common symptom of gallstones, but, fortunately, it is usually a self-limited symptom. There are, however, more serious complications of gallstones.

Cholecystitis means inflammation of the gallbladder. Like biliary colic, it too is caused by sudden obstruction of the ducts, usually the cystic duct by a gallstone. In fact, cholecystitis may begin with an episode of biliary colic. Obstruction of the cystic duct causes the wall of the gallbladder to begin secreting fluid, but for unclear reasons, inflammation sets in. At first, the inflammation is sterile, that is, there is no infection with bacteria; however, over time the bile and gallbladder become infected with bacteria that travel through the bile ducts from the intestine.

With cholecystitis, there is a constant pain in the right upper abdomen. The inflammation extends through the wall of the gallbladder, and the right upper abdomen becomes particularly tender when it is pressed or even tapped. Unlike with biliary colic, however, it is painful to move around. Individuals with cholecystitis usually lie still. There is fever, and the white blood cell count is elevated, both signs of inflammation. Cholecystitis usually is treated with antibiotics, and most episodes will resolve over several days. Even without antibiotics, cholecystitis often resolves. As with biliary colic, movement of the gallstone out of the cystic duct and back into the gallbladder relieves the obstruction and allows the inflammation to resolve.

Cholangitis is a condition in which bile in the common, hepatic, and intrahepatic ducts becomes infected. Like cholecystitis, the infection spreads through the ducts from the intestine after the ducts become obstructed by a gallstone. Patients with cholangitis are very sick with high fever and elevated white blood cell counts. Cholangitis may result in an abscess within the liver or sepsis. (See the discussion of sepsis that follows.)

Gangrene of the gallbladder is a condition in which the inflammation of cholecystitis cuts off the supply of blood to the gallbladder. Without blood, the tissues forming the wall of the gallbladder die, and this makes the wall very weak. The weakness combined with infection often leads to rupture of the gallbladder. The infection then may spread throughout the abdomen, though often the rupture is confined to a small area around the gallbladder (a confined perforation).

Jaundice is a condition in which bilirubin accumulates in the body. Bilirubin is brownish-black in color but is yellow when it is not too concentrated. A build-up of bilirubin in the body turns the skin and whites of the eye (sclera) yellow. Jaundice occurs when there is prolonged obstruction of the bile ducts. The obstruction may be due to gallstones, but it also may be due to many other causes, for example, tumors of the bile ducts or surrounding tissues. (Other causes of jaundice are rapid destruction of red blood cells that overwhelms the ability of the liver to remove bilirubin from the blood or a damaged liver that cannot remove bilirubin from the blood normally.) Jaundice, by itself, generally does not cause problems.

Pancreatitis means inflammation of the pancreas. The two most common causes of pancreatitis are alcoholism and gallstones. The pancreas surrounds the common bile duct as it enters the intestine. The pancreatic duct that drains the digestive juices from the pancreas joins the common bile duct just before it empties into the intestine. If a gallstone obstructs the common bile duct just after the pancreatic duct joins it, the flow of pancreatic juice from the pancreas is blocked. This results in inflammation within the pancreas. Pancreatitis due to gallstones usually is mild, but it may cause serious illness and even death. Fortunately, severe pancreatitis due to gallstones is rare.

Sepsis is a condition in which bacteria from any source within the body, including the gallbladder or bile ducts, enter into the bloodstream and spread throughout the body. Although the bacteria usually remain within the blood, they also may spread to distant tissues and lead to the formation of abscesses (localized areas of infection with formation of pus). Sepsis is a feared complication of any infection. The signs of sepsis include high fever, high white blood cell count, and, less frequently, rigors (shaking chills) or a drop in blood pressure.

A fistula is an abnormal tract through which fluid can flow between two hollow organs or between an abscess and a hollow organ or skin. Gallstones cause fistulas when the hard gallstone erodes through the soft wall of the gallbladder or bile ducts. Most commonly, the gallstone erodes into the small intestine, stomach, or common bile duct. This can leave a tract that allows bile to flow from the gallbladder to the small intestine, stomach, or the common bile duct. If the fistula enters the distal part of the small intestine, the concentrated bile can lead to problems such as diarrhea. Rarely, the gallstone erodes into the abdominal cavity. The bile then leaks into the abdominal cavity and causes inflammation of the lining of the abdomen (peritoneum), a condition called bile peritonitis.

Ileus is a condition in which there is an obstruction to the flow of food, gas, and liquid within the intestine. It may be due to a mechanical obstruction, for example, a tumor within the intestine, or a functional obstruction, for example, inflammation of the intestine or surrounding tissues that prevents the muscles of the intestine from working normally and propelling intestinal contents. If a large gallstone erodes through the wall of the gallbladder and into the stomach or small intestine, it will be propelled through the small intestine. The narrowest part of the small intestine is the ileocecal valve, which is located at the site where the small intestine joins the colon. If the gallstone is too large to pass through the valve, it can obstruct the small intestine and cause an ileus. Gallstones also may cause ileus if there are other abnormal narrowings in the intestine such as a tumor or scarring.

Cancer of the gallbladder usually is associated with gallstones, but it is not clear which comes first, that is, whether the gallstones precede cancer and, therefore, could potentially be the cause of cancer or the gallstones form because cancer is present. Cancer of the gallbladder arises in less than 1% of individuals with gallstones. Therefore, concern about the future development of cancer is by itself not a good reason for removing the gallbladder when gallstones are present.

Longitudinal and axial scans through the gallbladder show layering of sludge (S) in the gallbladder.

Longitudinal and axial scans through the gallbladder show layering of sludge (S) in the gallbladder. Sludge is a common term that is applied to an abnormality of bile that is seen with ultrasonography of the gallbladder. Specifically, the bile within the gallbladder is seen to be of two different densities with the denser bile on the bottom. The bile is denser because it contains microscopic particles, usually cholesterol or pigment, embedded in mucus. (The mucus is secreted by the gallbladder.) Over time, sludge may remain in the gallbladder, it may disappear and not return, or it may come and go. As discussed previously, these particles may be precursors of gallstones, and they occur often in some situations in which gallstones frequently appear, for example, rapid weight loss, pregnancy, and prolonged fasting.

Nevertheless, it appears that sludge goes on to become gallstones in only a minority of individuals. Just to make matters more difficult, it is not clear how often - if at all - sludge alone causes problems. Sludge has been blamed for many of the same symptoms as gallstones-biliary colic, cholecystitis, and pancreatitis, but often these symptoms and complications are caused by very small gallstones that are missed by ultrasonography. Thus, there is some uncertainty about the importance of sludge.

It is clear, however, that sludge is not the equivalent of gallstones. The practical implication of this uncertainty is that unless an individual's symptoms are typical of gallstones, sludge should not be considered as a possible cause of the symptoms.

Ideally, it would be better if gallstones could be prevented rather than treated. Prevention of cholesterol gallstones is feasible since ursodiol, the bile acid medication that dissolves some cholesterol gallstones, also prevents them from forming. The difficulty is to identify individuals who are at a high risk for developing cholesterol gallstones over a relatively short period of time so that the duration of preventive treatment can be limited. One such group is obese individuals losing weight rapidly with very low calorie diets or with surgery. The risk of gallstones in this group is as high as 40% to 60%. In fact, ursodiol has been shown in several studies to be very effective at preventing gallstones in these individuals. It is important to stress that no dietary changes have been shown to treat or prevent gallstones.

A doctor discusses gallstone prevention and possible after-effects of removal with a patient in the hospital. Current scientific studies are directed at uncovering the specific genes that are responsible for gallstones.

A doctor discusses gallstone prevention and possible after-effects of removal with a patient in the hospital. Current scientific studies are directed at uncovering the specific genes that are responsible for gallstones. Gallstones usually are diagnosed by a gastroenterologist, a medical subspecialist who deals with diseases of the intestine, liver, pancreas, and gallbladder. General surgeons also may be involved in the diagnosis of gallstones but usually are the doctors who treat gallstones because the common treatment is surgical removal of the gallbladder.

It is clear that genetic factors are important in determining who develops gallstones. Current scientific studies are directed at uncovering the specific genes that are responsible for gallstones. To date, 8-10 genes have been identified as being associated with cholesterol gallstones, at least in animals that develop cholesterol gallstones. Not surprisingly, the products of many of these genes control the production and secretion (by the liver) of cholesterol, bile acids, and lecithin. The long-term goal is to be able to identify individuals who are genetically at very high risk for cholesterol gallstones and to offer them preventive treatment. An understanding of the exact mechanism(s) of gallstone formation also may result in new therapies for treatment and prevention.

Surgery for gallstones has undergone a major transition from requiring large abdominal incisions to requiring only tiny incisions for laparoscopic instruments (laparoscopic cholecystectomy). It is possible that there will be another transition. Surgeons are experimenting with a technique called natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES). NOTES is a new technique for accomplishing standard intra-abdominal surgery, but access to the abdomen is through a natural orifice - the mouth, anus, or vagina.

For NOTES , a flexible endoscopic instrument is similar to the flexible endoscopes presently being used widely is introduced through the chosen orifice, through an incision somewhere inside the orifice (for example, the stomach), and into the abdominal cavity. Thus, the only incision is within the body and not visible on the body's surface. There are potential advantages to this type of surgery, but it is in the early stages of development, and it is unclear what the future role of NOTES will be in gallbladder surgery. Nevertheless, several series of patients have already been described who have had their gallbladders removed via NOTES primarily through the vagina.

Wie man das Fortschreiten von Arthritis verhindert

Osteoarthritis, allgemein als Verschleißarthritis bezeichnet, ist die häufigste Form von Arthritis und betrifft über 30 Millionen Amerikaner. Personen, bei denen Osteoarthritis diagnostiziert wurde, m

Wie man das Fortschreiten von Arthritis verhindert

Osteoarthritis, allgemein als Verschleißarthritis bezeichnet, ist die häufigste Form von Arthritis und betrifft über 30 Millionen Amerikaner. Personen, bei denen Osteoarthritis diagnostiziert wurde, m

Hernien:Ursachen, Arten und Behandlungen

Was ist ein Leistenbruch? Selbst wenn Sie kein Sixpack haben, hat Ihr Bauch immer noch Muskelwände, die Sie stützen, Ihnen helfen, sich zu bewegen und die Dinge in Ihnen an Ort und Stelle zu halten.

Hernien:Ursachen, Arten und Behandlungen

Was ist ein Leistenbruch? Selbst wenn Sie kein Sixpack haben, hat Ihr Bauch immer noch Muskelwände, die Sie stützen, Ihnen helfen, sich zu bewegen und die Dinge in Ihnen an Ort und Stelle zu halten.

Wie man Morbus Crohn auf natürliche Weise besiegt

Die körperlichen Komplikationen von Morbus Crohn allein reichen aus, um es zu einer der am stärksten beeinträchtigenden Verdauungskrankheiten zu machen. Aber es gibt auch den mentalen und emotionalen

Wie man Morbus Crohn auf natürliche Weise besiegt

Die körperlichen Komplikationen von Morbus Crohn allein reichen aus, um es zu einer der am stärksten beeinträchtigenden Verdauungskrankheiten zu machen. Aber es gibt auch den mentalen und emotionalen